Article begins

It is early spring in West Bohemia. In the forest, the retreating snow has exposed hundreds of white plastic cups to the pale sunshine. They sit on a layer of spruce needles and occasional tufts of grass like surreal eggshells crushed under the paws of an unknown giant creature. But unlike eggshells, these shiny plastic pieces will take ages to decompose. Where did they come from? Who is responsible for such conspicuous littering?

In the Czech Republic, like elsewhere around the world, landfills supply the major means for storing and containing human waste. Yet landfills are leaky. In West Bohemia, trees and shrubs in the vicinity of landfills are often wrapped in shreds of plastic or paper bags borne away by the updrafts, escaping the confines of the dump to decorate woodland branch and bush. Old furniture, car tires, or construction debris lie by landfill fences, fly-tipped by people who refuse to pay a fee to dispose of their waste. At some landfills in the region, waste pickers process their findings at the outskirts of sites, leaving accumulations of unwanted matter behind them. Yet the cups adorning the forest floor were neither brought by the wind, nor the result of illegal dumping.

We find other plastic containers for various dairy products and condiments, the tin cans from ready meals, beer cans, and plastic bags for cat and dog treats. All bear some signs of damage: plastic cups are cut into strips, aluminum cans and thinner plastic containers are deformed and punctured. Various animal bones ranging from deer hip bones to chicken femora lie scattered among the discarded receptacles.

The culprits, the cause of all this misshapen litter, are a band of scavenging corvids with a pilfering habit. In addition to majestic kites, watchful hawks, and rollicking wagtails, a large number of ravens roost in the forest and nearby fields. We watch at lunch breaks or at the end of a shift, when landfill workers and truck drivers disperse, as two or three raven explorers swoop in, stark black, to reconnoiter for food scraps—a yoghurt cup, a soup can, a box of cereal. When they find something to their liking, they pick it up with their beaks and quickly fly to the safety of the trees beyond the perimeter fence. Each bird will make multiple trips a day.

The landfill itself is a large mound rising above the treetops of the surrounding woods. Its recultivated part looks like a hill covered with grass while the active area is full of different colors and shapes of garbage. It is soft and smelly. Every day, garbage trucks bring hundreds of tons of municipal solid waste, which is then crushed under the massive wheels of the front loaders. The landfill workers are aware of the ravens but the birds don’t give them any trouble. They are more troubled by wild boars who used to break through the fences and threaten the workers before the manager decided to reinforce the fences with iron rods. While the new fence creates a major obstacle for the large terrestrial animals it does not stop the birds.

We ask the landfill manager if he is aware of the ravens’ thieving activities. But he is a bit anxious about anybody sticking their nose into the spread of garbage from his landfill site. He knows about the littering and recalls a conversation with a local forester who complained about the ravens dropping plastic cups on his head. Yet the manager, his deputy, and the workers have no idea of the scale of the birds’ trashy exploits. Landfill workers frequently collect garbage blown away by the wind, but they cover only the immediate surrounding area. Nobody had imagined that the ravens’ litter-dropping operations covered an area of more than three square kilometers.

Ravens are highly intelligent and do not like being observed or tracked. The ravens we follow constantly keep track of any human movement with their brilliant vision. They rarely allow someone to get closer than 150 meters unless they silently hide in densely grown tree crowns. They even hide behind trunks in the woods or the irregular terrain at the landfill. They seem to minimize the chance of being shot or captured. Although they are officially protected as an endangered species in the Czech Republic, the reality is different. Hunters, foresters, and farmers we interview openly talk about a need to reduce the population growth of ravens scavenging on garbage. They argue that few ravens are acceptable but large flocks create disbalance in nature. Ravens can kill juveniles of various forest creatures, newborn calves, and even adult hares. Occasionally, we find dead raven bodies in the vicinity of wooden hides used by hunters, suggesting that the fear and rage directed towards these birds is real, and not all of them are careful enough to avoid being shot.

Historical perception of ravens is ambivalent. On the one hand, their intelligence and skills are marveled in Christian stories where ravens feed the saints or search for land after the Deluge. The Vikings believed that ravens were messengers of God Odin. On the other hand, the Latin root rapere refers to snatching, abducting, or raping. Ravens’ voracious appetite and ability to kill and tear apart bodies of both animals and humans made them emblems of war and death. In the popular Czech imagination, ravens are associated with evil. The fairy tale Seven Ravens depicts them as dark beings into which seven disobedient brothers were transformed by their mother’s curse. Also, a raven dominates the Schwarzenberg coat of arms where it pecks the head of a dead Turkish soldier as a reminder of the sixteenth century victory over the Ottomans. It is no coincidence that the most horrifying scene in a recent Czech movie based on Jerzy Kosiński’s novel The Painted Bird features ravens waiting to finish a small boy buried in the soil up to his neck. Farmers, hunters, and foresters share this perception of ravens. They tell us versions of a story in which ravens patiently wait for an opportunity to peck out the eyes of baby calves on the nearby pastures.

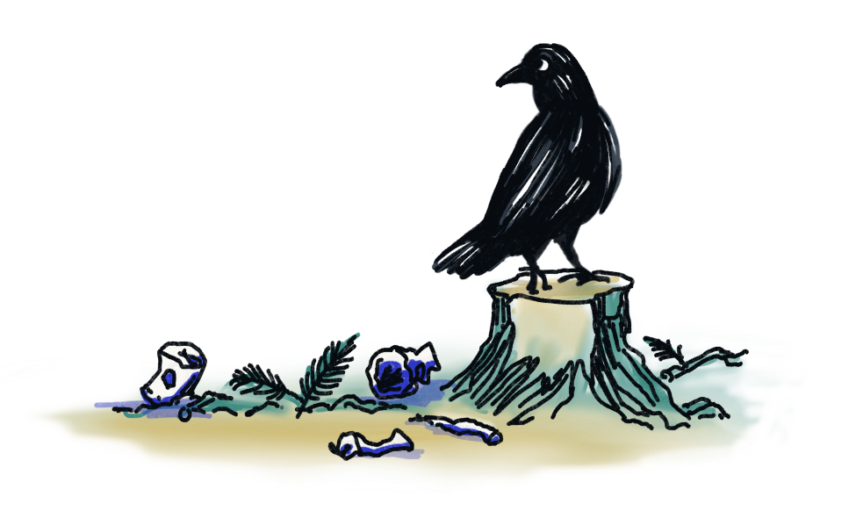

To enhance our ability to observe ravens’ activities, we install photo traps in places where the accumulations of discarded containers suggest intensive activities. This allows us to watch the elusive birds in action and learn about their techniques of getting food waste from the containers. They grab a yoghurt cup, for example, jump on a stump, and use it as a platform. They hold the container with their claws while cutting the wall into strips with their beaks. Repeating this process, they transform the cup into a mop-like object and easily access the food at the bottom. But we learn much more about the multispecies encounters with human waste beyond the fences of the landfill. Our traps capture other creatures. Hawks come to these garbage hotspots and consume food waste near ravens on the ground despite being known as their predators. We observe occasional skirmishes in the sky but abundant resources at the landfill reduce the mutual tensions. Families of wild boar sniff around the stumps and examine the deformed containers left by the ravens. Deer and mouflons come, attracted by the smell of food remains, but do not stay long because the spectrum of food does not entirely fit their needs. Feral cats and foxes also search to see whether there might be any food left that the ravens could not utilize. The occasional spotting of ravens with damaged tail feathers, however, suggests that not all encounters are friendly. Other predators seem to attack the ravens when an opportunity arises.

What initially seemed like polluted forest areas turn out to be loci of rich interspecies coexistence based on ravens’ capacity to transport resources out of the landfill and create affordances for other species. The ravens simply extended the potential to salvage value from human food waste. Food containers are mobile; they travel along trails forged by numerous terrestrial creatures who take advantage of the landfill litter and disperse it further, across the forest floor. Paradoxically, the hated ravens turn out to be the primary actors responsible for attracting hunters’ game—mainly boars and deer. We can only speculate to what degree this might be an intention of the ravens, to increase their chances of scavenging on the carcasses of hunters’ victims. Corvid cognition, as Thomas Bugnyar and colleagues demonstrate, is highly developed and capable of sophisticated anticipation and planning. Ravens can collaborate to outsmart their interspecies competitors or use tricks to fool each other. The ravens we study prove these capacities. They watch us carefully, anticipate our movement in the landscape, inform each other, and always try to be a step ahead of us.

Over time, we realize that ravens’ interests go beyond the simple utilitarian model of food provisioning. In addition to the food containers, we come across various strange objects such as rubber or plastic toys, small parts of electrical devices with unusual shapes or colors, razor blades, hand creams, and toothpastes. These objects confirm ravens’ curiosity and openness to experimentation more generally. Ravens are indeed curious creatures, especially when it comes to unusual objects. They like to examine them, compare them to each other, and store them for future use. Their inquisitiveness goes far beyond food gathering or nest building. They are explorers.

Our encounters with ravens and their rubbish swiping teaches us that landfills and dumpsites cannot be sealed off from their surroundings. Garbage can be collected, transported, or smuggled away; wastewater created by “digestion” inside bodies of mass waste leaks through the cracks, even from supposedly isolated sanitary landfills; the perfume of decay and fumes from accidental fires travel with prevailing winds; noise produced by loaders and compacters circulates in space; light pieces of garbage rise with updrafts of spiraling hot air from the surface; and nonhuman organisms spread the waste about as well. Writing about the world’s contemporary environmental problems, philosopher Michel Serres argues that these processes of emanation and percolation, which spread pollution in space, cannot be ascribed solely to humans. The multispecies relations and mutual entanglements of various forms of life in and around landfills further complicate not only responsibility for waste pollution but the very concept of pollution itself.

Pollution, as Serres points out, is premised on simultaneous appropriation and exclusion. Landfills offer a case in point. As pollution (human waste) invades space, it excludes humans who find it unbearable. The visual and olfactory signs of such polluted space—piles of garbage, malodorous smells—repel and discourage human presence. To keep the appropriation of space under control, the company running the landfill in West Bohemia reinforced the fences with iron rods, attached signs warning about the presence of electric wires, and installed a surveillance system, making a clear statement: “Wild boars, waste pickers, and other terrestrials, you are not welcome!” Ravens, however, are too cunning to be so easily pushed away. They use their intelligence and skills to take advantage of available resources and extend the appropriation of space by pollution. This polluting activity is not necessarily collaborative, but it is certainly hybrid. Ravens and other organisms defy human attempts to contain our waste. Standing amid plastic cups dispersed in the woods outside of the landfill, the question of who pollutes becomes difficult to answer. Neither a single understanding of pollution nor a single attribution of responsibility seems to work well here.

Our research joins a recent movement to reconceptualize pollution and its basic premises. We join Max Liboiron’s call to move beyond ideas about quantifiable thresholds and the universal nature of pollution that dominate public and policy debates on waste. Our more expansive-cum-situated understanding builds on Serres’s idea that pollution is a capacity shared across a spectrum of organisms. In the forest in West Bohemia this includes ravens, boars, deer, foxes, and others who engage in various trashy social relations. Humans generate garbage and dispose of it at the landfill. Birds transport food waste out of the landfill and attract their fellow forest creatures who transport various food-related containers even further. All these actors take part in polluting activities. At the same time, our experience around the landfill shows the ambiguities and contradictions of pollution. For some, woods full of plastic cups may be disturbing. For the waste management company, the same cups may call into question the limits of its power and responsibility. For the ravens and other organisms in the woods, the same cups may represent a blessing, a vehicle of multispecies coexistence, or an object of playful dwelling. There are, the cups show us, many lively, more-than-human forms of life associated with landfills.

This story has an uncertain future. As pressure for more sustainable means of waste management increases in the European Union, we might be getting closer to the end of landfilling as we know it. Ravens and their nonhuman fellows will have to find new habitats if the landfills they use become history.

Illustrator bio: Charlotte Corden is an illustrator and fine artist whose work often centers around what it is to be human. She has an MA in anthropology from University College London and has studied at the London Fine Art Studios and the Arts Students League of New York.