Article begins

*This essay includes scientific illustrations as well as descriptions of the observing and handling of primate bones and bodies.

On a summer afternoon in 2004, I found myself staring into the teeth of an adult male baboon. The bared canines, three inches long, were honed to a razor’s edge on one side and tapered to wicked points at the ends. I was on the fourth floor of the social sciences building on the University of California Santa Cruz campus. In my hand I held a perfectly preserved skull, one of many in Adrienne Zihlman’s extensive collection of primate skeletons.

Creating images on paper has been part of my life for as long as I can remember. Drawn to the natural world, flora and fauna filled my sketchbooks and were the subjects of my paintings. My path to illustrating primates, in particular the apes, began with my work in assisting Zihlman’s decades-long research, gathering data through primate dissections. As artist and natural history enthusiast the opportunity to see these rare animals up close and study their locomotor mechanics fascinated me.

After months in the lab and many brain-storming sessions, we settled on the idea of writing a book that would bring together all four genera of apes, Hylobatids, Pongo, Gorilla, and Pan. Our goals were to treat each genus individually, including information on diet, behavior, distribution, evolutionary history, and anatomical data, and to apply comparative anatomy to elucidate similarities and differences between the apes. We wanted to create a book that would appeal to students of all ages, to researchers in the field and in the lab. After years of work our vision was realized with the publication of Ape Anatomy and Evolution.

A deep dive into dissection

Part of the dissection methods were to record external measurements, thus providing me with a chance to note details such as color, length, and direction of hair growth over body regions; size and shape of hands and feet, including textures of the palms and soles; and facial features. The shape of the nose, size of the ear relative to the head, and placement of the eyes are critical details that bring the artist one step closer to a truer replication of the face. The act of dissecting, however, took me beyond observation. It is a deep dive through layers of tissues, an unfolding of the body that reveals the relationships of structures giving form to the body, and propelling the animal through life. Gently raising the forelimb exposes the inner workings of the shoulder joint and the muscles that powered the movement: the clavicle raises, the humeral head rotates against the shallow glenoid fossa of the scapula, the tendon of the pectoralis major stretches, and the muscle belly of deltoid bunches up as if in contraction. Movement at the joints and muscle attachments relative to their boney counterparts were noted and occasionally sketched, though I relied heavily on my photographs for later reference.

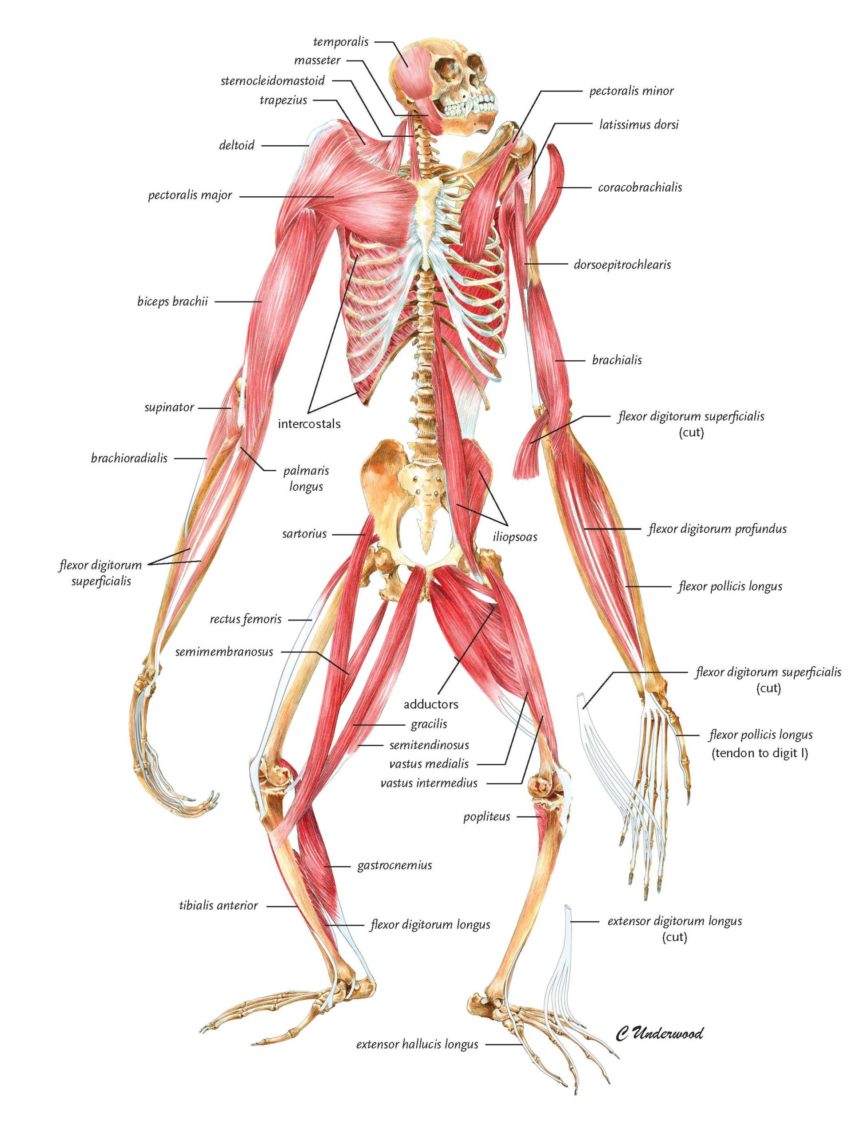

I had worked primarily on Hylobatids (gibbons and siamangs), and so began with a painting of a female Hylobates lar skeleton. Her slender bones fit easily into my backpack, so getting her home to my apartment was a breeze. My kitchen table was not always set for company, but was a perfect stage for my muses. I chose to illustrate a bipedal position, not because gibbons most often use this in their locomotion, but to provide the most complete view of the bones. I rendered a detailed graphite drawing, transferred it to watercolor board, and scanned the final completed painting. To layer the muscles, I laid tracing paper over the top of the skeleton drawing and penciled in individual muscles, using dissection photos and notes for attachment and relative position. As before, this drawing was transferred, painted, and scanned. In Photoshop I removed the white background from around the muscles and placed the image in a layer over the scanned skeletal painting.

This composite painting eventually led to a series of 16 images for our book, in which each ape skeleton is depicted in anterior and posterior views, and again with muscle overlays. The gibbon muscular system received more detail as visual material of their anatomy was so little represented in the literature.

The dynamic animal

The five-year-old gorilla charged down the path pausing only long enough to throw a fistful of dirt in the face of the 400lb silverback before spinning off to wrestle with an older brother. I spent a week at the San Diego Zoo to observe ape locomotion; filming by day, sketching from memory at night. My loose charcoal drawings captured their dynamic movements as well as resting postures.

When walking on the ground gorillas and chimpanzees knuckle-walk and use a heel strike at the foot, whereas orangutans close their long fingers into a fist, and flex their long toes as they bear weight on the lateral foot. Gibbons rarely bear weight on their delicate hands, but will sometimes rest their forelimbs on the backs of their wrists. Hand and foot positions differ among the apes and as first points of contact with their habitats are of primary concern to the artist, as a wrongly positioned appendage will make an unconvincing (and incorrect) drawing.

I was able to view the nearly 180-degree separation they can achieve between digits I and II (our thumb and index finger) when they grasp a support. Their slight body is the perfect size and form for airborne leaps; in the wild they can cross gaps between trees as wide as 30 meters!

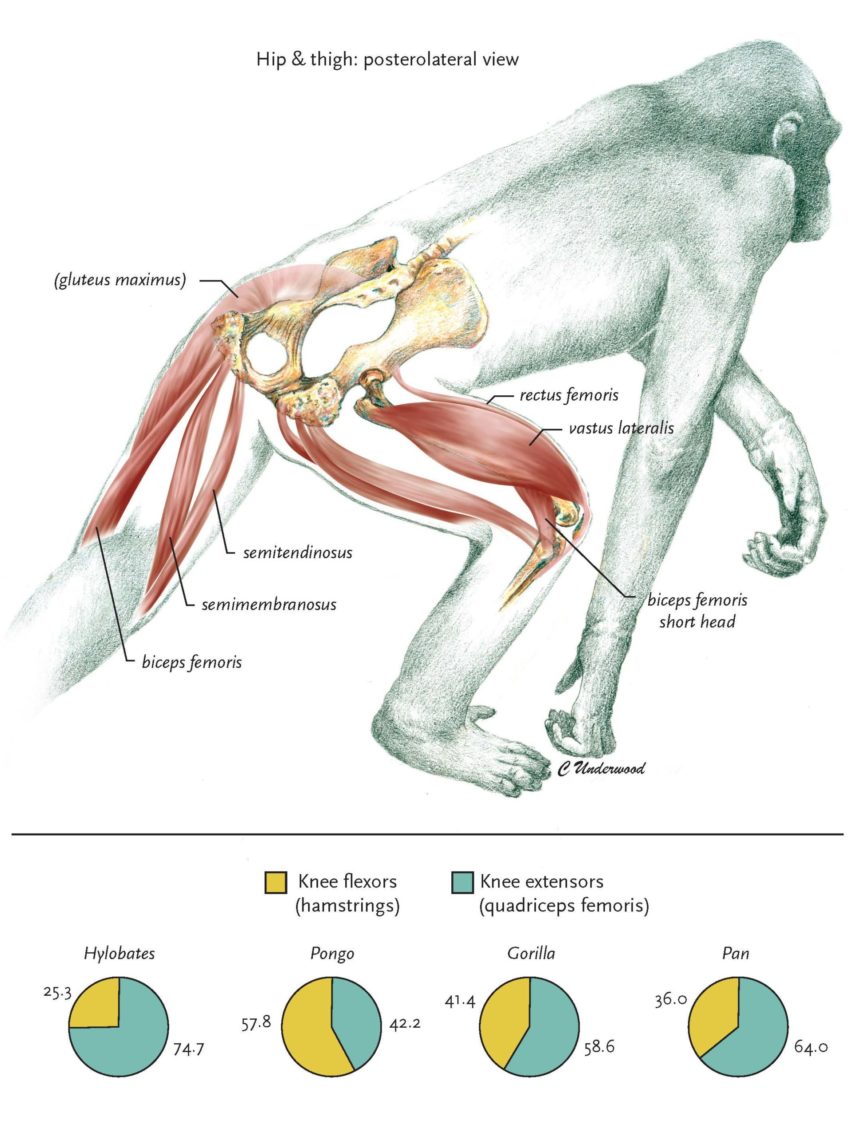

Orangutans can at times strike the most convoluted, ungainly poses. Joint mobility allows them to twist their limbs into positions humanly impossible. I illustrated an orangutan in a typical posture in the trees, showing the posterior view of the thigh with the calf segment rotated and the foot rotated further to show the dorsal (or top) view. A colleague commented that I had the foot on backwards! Mortified, I returned to the original photograph only to discover it was indeed drawn correctly. Contortionists!

Though all apes can move over the ground quickly, they are adapted to forested habitats and it is among the trees where their locomotor abilities excel. Reviewing my films frame by frame was the only way to isolate airborne positions of the gibbons and chimpanzees. The chimpanzee’s muscular form is often visible through sparse hair at the shoulders and thighs, revealing a powerful body. Deltoid and biceps brachii bulge beneath the skin of the arm, adductors and quadriceps at the thigh. They leap between supports, hang and swing from ropes by long powerful forelimbs, and climb tall vertical posts with vigor and ease. I wanted to capture their dynamic movements on paper for a painting as I imagined them in their natural environment deep in a Congolese forest.

I observed gibbons and siamangs up close at the Gibbon Conservation Center in Southern California. I was able to view the nearly 180-degree separation they can achieve between digits I and II (our thumb and index finger) when they grasp a support. Their slight body is the perfect size and form for airborne leaps; in the wild they can cross gaps between trees as wide as 30 meters!

The apes that I watched and photographed had a way of getting under my skin, too. They are expressive and inquisitive, playful and deeply bonded within their group. As I observed the apes in life, I was reminded of artist Joel Ito’s captivating depictions of primate motions and emotions. I sought to emulate his sensitivity in my watercolor paintings that depicted the apes moving through their natural habitat, interacting with one another, at home in the wild.

Proportion, perspective, and inspiration

Observing the animals in motion complemented my anatomical studies, but I couldn’t live at the zoo, and although dissection enhanced my understanding of locomotion, it was only a fleeting glimpse inside the body. And so I found Zihlman’s skeletal collection a wonderful opportunity to study comparative anatomy at a more leisurely pace.

I relied on visual references during dissections to aid in identification of individual muscles and guide me through the body. The best images lent clarity both during and after dissection. Adolf Schultz, an anthropologist whose technical precision in pen and ink renderings of primate anatomy featured in The Anatomy of the Gorilla (Raven and Gregory, 1950) motivated me to pick up the pen again.

With a wealth of resources and inspiration, I searched through the cabinets in the lab looking for my first subject—of course, the fabulous baboon skull! I added more monkeys to the lineup—langurs, patas, macaques and vervets—to study differences between species and between monkeys and the apes. Dentition, limb proportions, and the rib cage differ dramatically. I rendered the gibbon’s long bones in pen and ink, completed a life-size drawing in graphite of a gorilla’s rib cage, and a life-size langur skeleton too. I painted the chimpanzee skull in watercolor, and drew the skulls of each of the apes from multiple angles, noting similarities and differences.

These exercises focused my attention on the details before me, but I wanted to create layered images that brought skin, muscle, bone, and the animal together. Doug Cramer, anthropologist-artist, had worked with Zihlman in the past, so many of his originals were available to me. He was expert at illustrating anatomy from unusual perspectives and conveying the multilayered body. His work was inspirational. I printed out my photos of apes and sketched in muscle and bone over the top. Grappling with challenges such as foreshortening the pelvis as the animal in my photograph walked away from me became decidedly easier as I selected a pelvis from the drawer and propped it up at the appropriate angle.

In developing anatomical illustrations my goals are to give perspective to the moving parts beneath the skin while retaining an essence of the living animal. I also want to invite the viewer in by making a potentially unfamiliar subject familiar. A simplified body outline acts as a map of sorts to help orient the viewer. Contrasting soft sketch quality lines with sharply defined areas, or grey scale with a region of color helps guide the eye to key elements. These subtle clues direct attention to the focal aspect of an image and help create a seamless integration for the reader between text and visuals.

Though our book is published, my portrayal of all things ape—and beyond—continues with Zihlman’s future plans for a book on chimpanzees where I hope to do some portrait-style paintings. Work for Debra Bolter, an expert in growth and development with current and ongoing research on early human australopiths offers me opportunities to illustrate fossils. Nearing completion is Ted Grand’s book, Rethinking Comparative Biology: Integrating Anatomy, Behavior, Development, and Evolution that includes my illustrations of South American primates, along with many more species. Each new project is an opportunity to bring together techniques and styles of creating for new interpretations of a subject.