Article begins

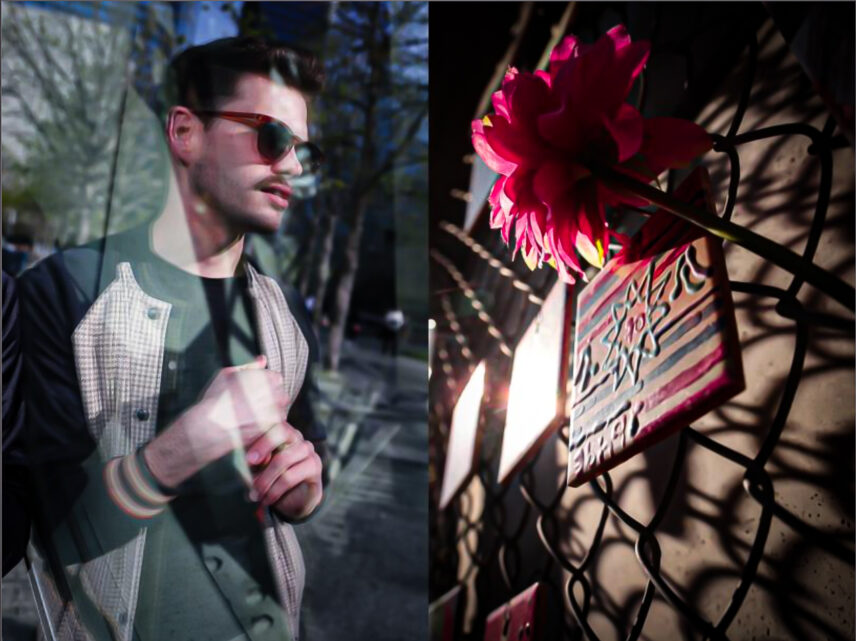

This long-form documentary photography project investigates how historical events are taught and remembered by examining how and what the post-9/11 generation has learned about the events of September 11 and its impact in the United States and abroad. With a focus on the experiences of those who were born shortly before and after 2001, this project explores personal and collective memories from the perspective of Gen Z and young Millennials whose memories or knowledge of that day were mostly formed by parents, caregivers, and community in the months and years after the event. Participants were voluntarily recruited for this project through email advertisements and word of mouth. Throughout our interviews and portrait sessions, we acknowledged the theme of silence – whether represented in a “moment of silence” to honor those whose lives were lost on that day or by a societal silence around how and what they have been taught about 9/11 and the ramifications of the “war on terror” both domestically and abroad. Considering current legislated censorship on history and social studies curriculums in schools throughout the United States, coupled with rising incidents of hate crimes against communities of color, this project has shed light on the missed opportunities to learn from mistakes of the past.

When war is discussed broadly in the United States, oftentimes the lens is placed elsewhere, far away, with little or no introspection on ongoing US transgressions abroad. Since 2001, the United States has been in a cycle of endless wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, Pakistan, and Yemen with additional “counterterrorism operations” reaching 85 countries globally. “The war on terror” was declared by President George W. Bush shortly after the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks on September 11. The war on terror was never declared against any specific country, state, or territory; it is a vague term used to describe the United States’ ongoing international military campaign launched primarily against targets in the Middle East and surrounding countries. Although President Obama declared the war on terror over in May 2013, the US remained in Afghanistan until September 11, 2021, and still has roughly 2500 US soldiers scattered throughout Iraq. According to 2023 figures from the Watson Institute of International & Public Affairs at Brown University, the number of people killed indirectly in post-9/11 war zones, including in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, are estimated at 3.6–3.8 million, though the precise figure remains unknown.

Many of the young people featured in this project discussed not having memories of the day but feeling the impact of September 11 through stories passed down by family and community members. One participant recalls hearing about how “in the old days, if you flew alone, a family member could walk you to the gate.” They had a hard time imagining that scenario, as the militarization of their schools, airports, and public spaces is their current reality. “I have friends and cousins who were born in 1994 and 1995 who remember traveling to Disney in the ‘old’ way and they remember the switch. I don’t. I just remember that in my lifetime this switch happened . . . for everything,” recalls Luke, a participant born in the year 2000.

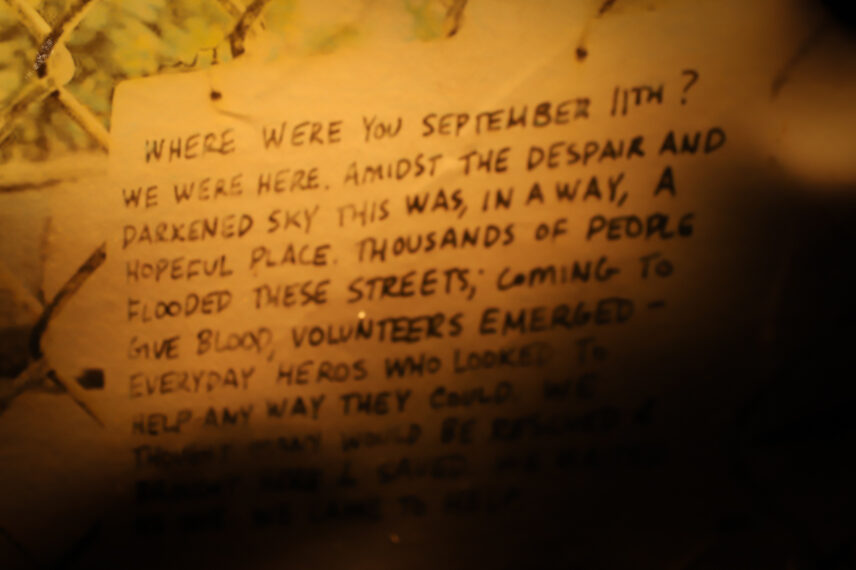

Some participants first learned of the attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon in social studies classes and annual “moments of silence” in their elementary and middle schools. At first, they recalled confusion surrounding why there was a moment of silence without further explanation or context. In each school, the moment of silence reflected the community. “The moment of silence would be a prayer. Since I went to Catholic school it would be a Hail Mary or Our Father. It would be a moment of silence to remember the firefighters who died and the people working there. They had us say the prayers in our head,” recalls one participant. Another participant who attended public school specifically mentioned a series of “September 11 Coloring Pages” their school would share with first and second graders. The moment of silence was spent coloring images of firefighters, American flags, and EMS workers. There was no further explanation provided to the students about why they were coloring the selected images. “I think they were trying to be age-appropriate about it,” the former student recalls. Later, they also admitted feeling misled about the history of the response to the attacks, including the international impact of the war on terror and antiwar protests that emerged domestically and globally. “When we talk about 9/11 it’s mostly about how much we hate the Patriot Act surveillance, and how much we hate the wars in the Middle East, like the wars for oil. We never talk about the actual event. We never talk about the towers, unless of course, it is the day of 9/11,” adds Luke. “Sometimes I go there, to the site, and I look up, and I imagine the towers based on images I’ve seen but I can never really picture it,” he concludes.

The general silence around the aftermath and impact of the United States’ response became a recurring theme for the participants, many of whom continue to feel the effects of post-9/11 through Islamophobia, increased surveillance, security, and domestic and international policies. Some participants felt that the focus on international terrorism took the attention away from their real fears of domestic terrorism, including active shooters in schools, movie theatres, libraries, and other spaces they frequent. Each participant noted a personal experience of active shooter events, whether in their school or nearby community.

These photographs are part of a multidisciplinary project with a documentary theatre component that began in 2011 with “10 Years Later” (2011) and “20 Years Later” (2021), created in collaboration with the New York-based theatre companies Co-Op Theatre East, Project Girl Performance Collective/Girl Be Heard, and Docbloc. A company of youth actors devised both theatre projects through autobiographical and verbatim interview-style techniques which were performed at venues throughout New York and New Jersey. Support for various components of this project was made possible through the CUNY Graduate Center’s Provosts Digital Initiatives Grant, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, the CUNY Center for Humanities “NY Connects” Grant, and the Publics Lab at CUNY Graduate Center.

“I was 6 when I became a Cub Scout at Pack 142.

At all the meetings, we’d often see this poster, this flag with a silhouette of New York City during sunset and words over them, Never Forget, 9/11/2001. I didn’t know what that meant at the time. I kept seeing it over and over again throughout my Cub Scout years . . .

Never forget? Never forget what?

It wasn’t until I left Pack 142 that I realized what we were never supposed to forget.

On October 31, 2017, I was sitting in my classroom at Stuyvesant High School, wondering why I couldn’t go home. We were locked down. They wouldn’t tell us any information—it was up to us to find out. I was in school, dressed as a cat, and we had to stay an extra 3 hours after school because several hundred feet away, a guy ran down Hudson River Park’s bike path with a rental truck and killed eight people because he heard from ISIS it’s better to strike terror on holiday. Politicians scrambled to take advantage of the moment: ‘the deadliest terror attack in NY since 9/11.’ It was already dark when we were dismissed, and nobody wanted to go trick or treating. Humanity is lost, nothing is found, and I don’t know what to think anymore.”

—Jason (born in 2000)

“I know many people who know somebody who died on 9/11 and others who have gotten cancer from 9/11. My dad swears he didn’t get sick after 9/11 because of this woman, a stranger, who had to be carried out of the towers by medics. She stopped to give him a rag to put over his face while they ran away from the buildings. I guess it shows that masks work, right?”

—Fiona (born in 1999)

“In my lifetime, throughout all of my schooling, we had lockdowns every time there was an active shooter nearby, so at least a handful of times a year. I was fortunate enough never to have been in a shooting myself, but on the news, I’ve seen plenty of kids get murdered. We have issues of domestic terrorism people don’t want to acknowledge in this country. 9/11 feels like another tragedy that happened in history, not that history doesn’t matter, but . . . so many tragedies are piling up daily; 9/11 is just another one.”

—Kristen (born in 1998)

“Each year, our teachers gave us a booklet on 9/11, and the whole morning we would color. I first learned about 9/11 through those coloring pages. They were coloring pages of the World Trade Center (before it was hit) and fire trucks. There were also pictures of American flags and people standing in front of the American flag, like firefighters, nurses, and the heroes, pledging allegiance to the flag. They were symbols of how great we are as a country. There was never much discussion other than, ‘this thing happened—we’re not going to explain, just color.’ The focus of those pages was always on how we were supposed to feel—sad, mad, and angry.”

—Toni (born in 2002)

“I saw the towers as a kid!

Actually, I can’t remember if I saw them or if I’ve seen so many photos of them that I think it’s my own memory. It’s one of those things, like Princess Diana . . . you remember her, but you don’t know how or why. The first time I actively remember seeing photos of the World Trade Center was in third grade, in textbooks . . . in the pictures of history books.”

—Melissa (born in 1998)

“I was never taught about 9/11 in school, but I grew up in a community where every year on 9/11, the principal would come over the intercom, and we would have a moment of silence. I was part of a generation of kids who didn’t even know why we were having a moment of silence. I have a younger sister who was born in 2005. She was taught about 9/11 in school. It’s a chapter in her history book. She has been taught more about it.”

—Max (born in 1997)

“I remember the first time I found out about 9/11, we were driving into the city and there was this block of space, and my mom said, ‘There were once towers there.’ We used to talk a lot about 9/11 in middle school. There would be firefighters who would come in and talk about taking bodies out of the building, and it was traumatic. I was 12 when they started doing this. We knew how bad it was, but we were shocked hearing how many people lost their lives and how affected people were.”

—Emma (born in 2003)

“I don’t know who did it.

I don’t think I know why it happened.

I don’t think I know what countries were involved.

I went to a small school in Brooklyn. I learned the surface level of it at school. I only learned that it was a terrorist attack against the Twin Towers. Nobody spoke about who it was or why. I think this was in 4th or 5th grade. It was a quick discussion in history class. It wasn’t in our textbook or talked about deeply. Was it ISIS who attacked? Was it two planes or three? I don’t know the details . . .

I know it’s affected my family. My father was born in Egypt, so when security sees his passport at the airport and they see he is from the Middle East, they automatically check his bag. It also happens on the subway with the police. His bag gets checked every single time. It still happens to this day.”

—Izzy (born in 2001)