Article begins

Uffe scaled the ladder up to his roof with ease. I was more uncertain, trying to dig under the foot of snow to find something to grasp without dropping the beer can clutched in my hand. He laughed as I peered down at the dogs barking from the safety of the ground. Standing firm he took the can and taped it to the TV aerial with the thick black tape I had bought at Arjeplog’s local convenience store. The February wind rocked the metal rod with its little colorful can. We removed the small “shutter” and, just like that, the camera was operational.

I got the idea from a YouTube video by Justin Quinnell (2012), in which the photographer shows students how to make pinhole cameras from soda cans. Doing this as fieldwork, I thought, could be a way to explore new modalities, following Ethiraj Gabriel Dattatreyan and Isaac Marrero‐Guillamón’s call to utilize media in inventive rather than descriptive ways to “generate relations” (2019, 220; see also Estalella and Sánchez Criado 2018). Amanda Ravetz, Anna Grimshaw, and Elspeth Owen have also proposed an “open ended” experimental approach to visual anthropology, in which they call for scholars to “try things out even though they might seem awkward, or puzzling” (2013, 150). Inspired by this work and keen to engage with more experimental processes, I instigated a number of different photographic methods with my friends and participants in the field to spark conversations about landscape.

The beer can cameras were by far the most fun. When I told Marianne, a friend and participant during fieldwork in northern Sweden, she was delighted. “We will have to work hard,” she said, “and drink beer for your PhD.” I rummaged in recycling bins to find old empty cans of Norrlands Guld. Norrland is the name of the northernmost part of Sweden, and “Gold of Norrland” cans are embossed with a landscape emblematic of this region: a vast lake framed by forest and mountains, a single boat, and a moose gazing into the distance. This was a brand well-suited for cameras designed to record the North. We bought new cans that were bright and cheerful, drinking the beer in the sauna and washing the metal in the kitchen sink. Photosensitive paper went into each can followed by a sharp pinprick to create an aperture and allow light to stream through and carry the landscape into the camera. The light from the scene projected an inverted image onto the paper; cans became cameras. We set them up in trees outside the house, on the aerial at my friend Uffe’s house, and on my balcony.

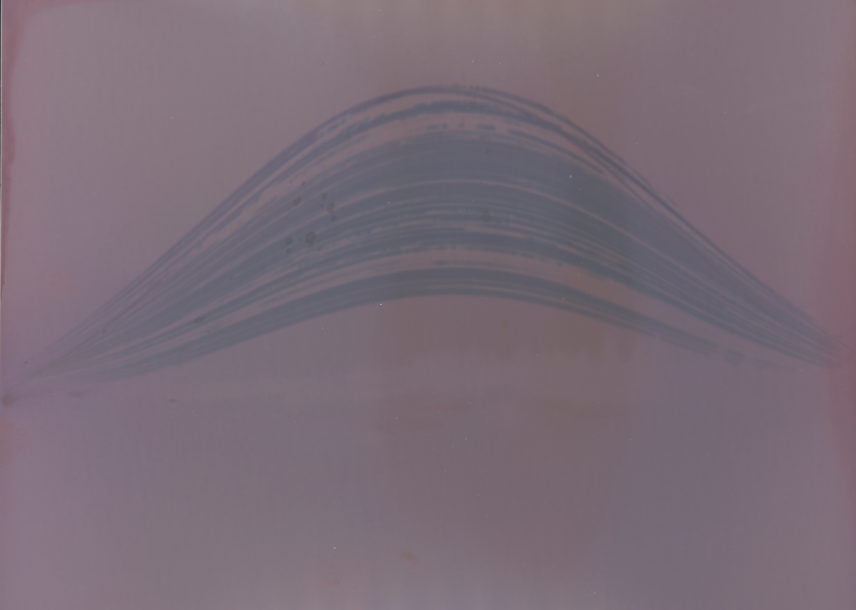

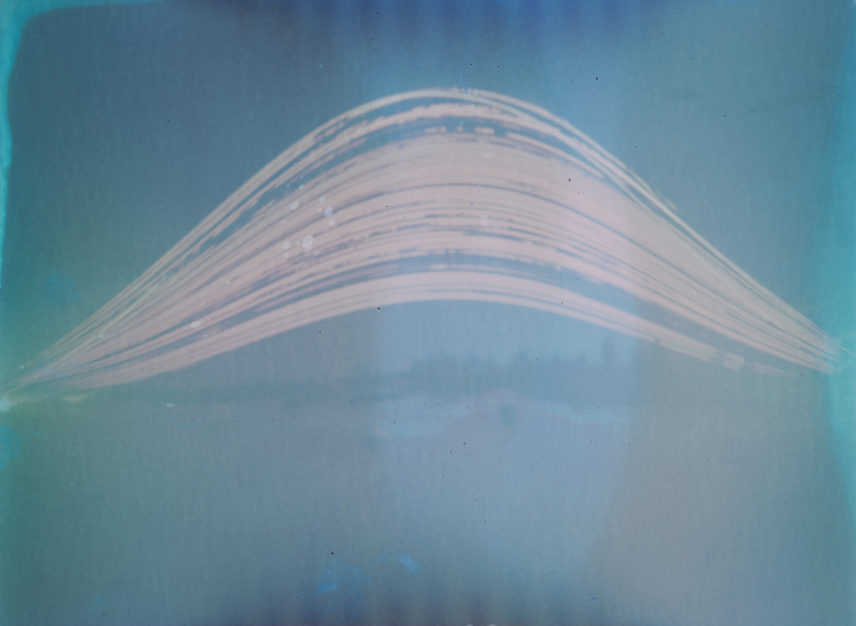

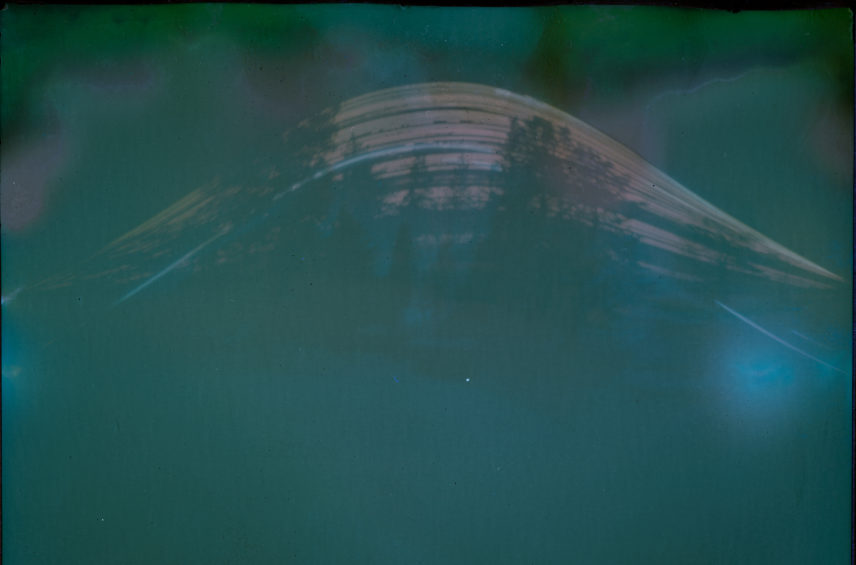

Once in place, and at the same time out of place, the cameras waited in the trees as the winter sun rose a little more each day and snow melted into summer. Through every snowstorm, every sunrise, every wandering moose or flock of birds, the cameras stayed in place as material interruptions in the subarctic landscape. They diligently recorded their changing surroundings in one frame. Each turn of the sun left an imprint seared across the chemical surface of the paper, rising each day toward midsummer and forming a pink lumen print. Digitally scanning and inverting the colors creates a positive version of the image: bluey green skies streaked with pink light. While the landscape in the foreground stays largely the same, the tracks are movement and change. Each streak of light is a new day, stretching across the paper and embedded in its surface.

As the world came into the cans through the light of the sun, the cameras were materially affected by the landscape and affected it in turn. On my balcony, and above Uffe’s TV aerial, the warmth of the houses protected the integrity of the paper, keeping it intact. Out in the trees the 35°C air shriveled it into a tight cylinder, revealing only a whisper of the tracks and streaks, invoking the movement of the northern lights.

As I pulled the paper out from the balcony camera, the edge caught against the rough-cut ring of the can and it ripped. When I scanned the paper this hole revealed the inner workings of the scanner itself. Pulling the tape from the trees pulled the old bark away with the cameras, leaving a rugged shadow of where the tape had melded with the material surface of the pine. The cameras interrupted the landscape, and left traces of their presence once removed.

Many people in Arjeplog did not want to engage with discourses of climate change, given conflicting notions of land use and environmentalism with the South (see also Bartlett, forthcoming). They waved their arms through the air in a representation of warming and cooling throughout Earth’s deep time, contextualizing current warming in a continuous natural pattern outside human influence. The sun tracks moved across the paper just as the arms moved through the air, both gestures of time passing on radically different scales.

In these images, the scales of time are also disrupted. The photograph becomes not one split-second moment but a long, slow process emplaced within the fieldsite. It is a record of six months, changing seasons, and changing landscape.