Article begins

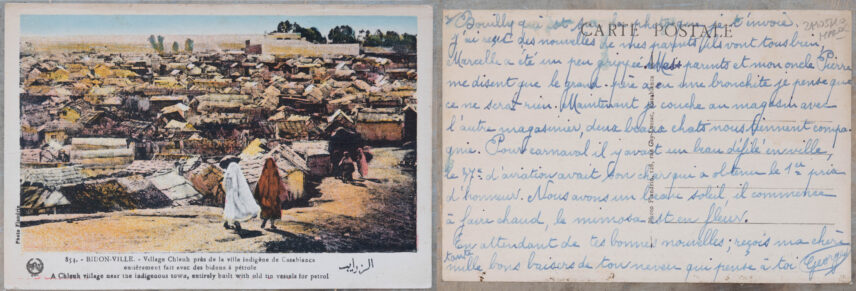

“BIDON-VILLE.―A Chleuh [a Berber group from southern Morocco] village near the indigenous town, entirely built with old tin vessels for petrol,” reads a postcard from Casablanca.

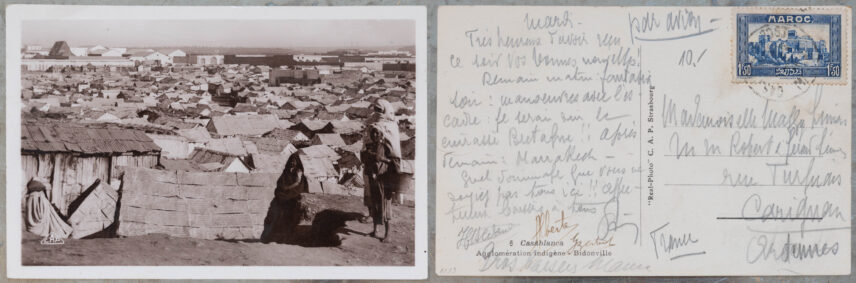

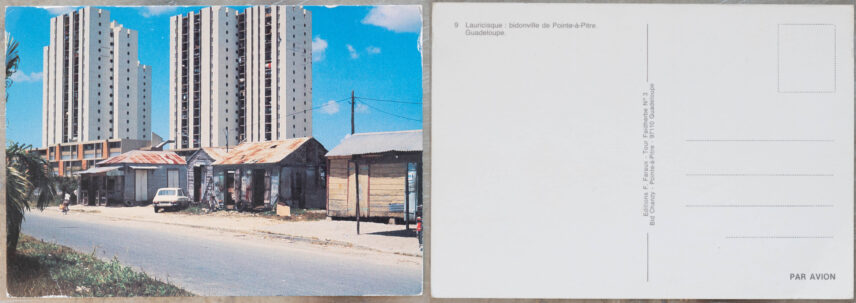

Coined in colonized Morocco and Tunisia as an administrative term for a settlement built from discarded jerry cans, from the 1930s onwards, bidonville (can city) became a powerful global idiom to delineate and define precarious peripheries of urban life.

Postcards and their circulation were crucial for this globalization. They sought to visualize what the term described. This visual assemblage, often scenes of tin can roofs stretching into the distance, then met with the everyday, personal writings of soldiers, colonial administrators, and tourists. “The grandfather had a bronchitis […] For carnival there was a nice parade in town […] We got a nice sun, it’s getting warm, the mimosa is in bloom […],“ someone named George wrote in French to their aunt on the back of one such postcard.

Tin houses and bronchitis, parades, mimosas. A paradoxical combination, yet one that helped to anchor bidonville in the quotidian life of the privileged; to generalize it, while consolidating the us versus other―first far away in the Maghreb, then at home in France. The world dichotomous; the creators and inhabitants of such places impure and dispossessed others, living a peripheral life in waste.

Yet from another perspective, the creators and inhabitants of so-called bidonvilles also ascribed new value to the residues of extractivism and “progress” and reappropriated them; they made a home and created a community amidst the metal tins and cans. Precarization does not silence subaltern agency and creativity, and as Anna Tsing writes about commodity chains and survival in damaged landscapes, life in ruins is possible. Moreover, we increasingly come to learn that peripheries and centers cannot be held apart, that nature-culture divides collapse, and that we live within interdependent, emergent worlds. It was with such a sense that the audiovisual installation Bidonmondes was conceived.

In the Sine-Saloum Delta, Senegal, 20L plastic canisters are omnipresent. They largely stem from Malaysia and Indonesia and are imported via the Gambia as palm oil canisters before delta inhabitants reuse and modify them in various ways.

Both oil and palm oil production are extractive and drivers of precarization and environmental ruination. Their offspring, the canisters, represent, take part in, and materially inherit processes of deforestation, enclosure, or the polluting of air, grounds, and waters that lead to displacement, loss of livelihood and biodiversity, and contribute to global climate change. As tangible and quotidian, yet always malleable objects, they provide sensuous access to such processes and relate various human and more-than-human actors―among them plantation workers, palm trees, and consumers―to each other across space and time.

In Bidonmondes, the canisters’ history is brought into correspondence with their various applications in the delta after the palm oil is consumed―their use as canisters for palm oil, water, and petrol and their modification into dustbins, sieves, and burning material. The different material and symbolic makings and remakings of oil and palm oil are explored across six audiovisual loops. They reconfigure, enlarge, and contrast imagery and sound. On the one hand, the imagery and sound around canisters in the Sine-Saloum Delta; on the other hand, the canisters’ inherited sounds―Malaysian logging, oil palm cutting, a palm oil industry advertisement, motorboat use, petrol production, and a petrol industry advertisement for offshore drilling near the delta. The video loops’ arrhythmicity and possible sequencing into one imperfect, endless cycle also point towards the unfulfilled human desire for infinite (re)production within a finite world.

Bidonville became a general term in the singular, circulated and reproduced across the world with the help of images and quotidian, personal stories told by the privileged. Thereby, Raffaele Cattedra writes, the individual experiences and the collective linguistic inventions of those living in and naming such places were erased; the history of the tin was rendered absent.

Bidonmondes keeps history present, held in plural, and gestures towards multiple worlds. By taking up the term bidonville and paying homage to the oeuvre of artist Romuald Hazoumé, whose mask and installation works mobilize petrol containers as postcolonial critique, it connects the agentive ways of living with and within residues in the French colonial empire and beyond with those in postcolonial Senegal. It contrasts them with both the continuities of extractivism and precarization and their twenty-first century acceleration and intensification.