Article begins

Contemporary images of Cubans in Florida as mainly White, right-wing, and affluent clash with the state’s involvement in Cuba’s late-nineteenth-century independence movement. In Key West and Tampa, Black and White Cuban émigrés worked together to free Cuba from Spanish colonial rule. Their struggle was part of a larger worldwide movement for human and labor rights—values strongly embedded in the cigar industry workforce. During a period of extreme racism and hardening segregation in Florida, Tampa hosted a large Cuban immigrant population, a good portion of it Black, as well as Spaniard and Italian. Collectively, they were working towards some version of international socialism, as were workers around the world.

Yet in the past and today, Tampa celebrates its historic role in what was ultimately called the Spanish-American War (April 21,1898–December 10, 1898), a framing that neglects the years during which Tampa Cubans toiled in support of Cuban independence. For the Cuban émigré community, it was the War of Independence (February 24, 1895–February 10,1898), subverted by a three-month US intervention. This brief American chapter of the war is remembered and reenacted in popular light-skinned renditions, but important roles played by Cuban South Florida, especially Black Cubans, have been largely erased in Tampa.

Many Black Cubans on both sides of the Florida Straits played prominent roles in fundraising, organizing, communications, fighting, and other key activities. We reinsert these lost figures into the narrative of Cuban independence and “Cubanness” in Tampa. Their lives and the continuing erasure of their contributions and experiences are part of a history and present colored by the pervasive effects of Jim Crow racism and the never-extinguished racism of Cuban and American slavery.

Cigarmaking was the lifeblood of Tampa’s immigrants, most concentrated in an enclave called Ybor City, named for the Spanish Cuban cigar magnate who founded it in 1885. By the 1890s, dozens of factories and thousands of workers composed an activist community determined to free Cuba and transform world politics, race being a major issue in the planned rebellion. About 15 percent of Cubans in Tampa were Black. They included journalists, labor organizers, and business owners—prominent members of Tampa’s revolutionary constituency. Many were close associates of José Martí, Cuba’s most revered hero, who visited Tampa frequently before his death in battle in 1895. He oversaw the Cuban Revolutionary Party (PRC) and planning of the war.

While there Martí usually stayed in a boarding house owned by Black Cuban patriots Ruperto and Paulina Pedroso. His public friendship with them was emblematic of his plea for Cuban racial solidarity. The site of their house, across from the Ybor factory, is now a park named for Marti. In the semi-official local narrative, the Pedrosos are lone representatives of Black Cuban revolutionists, Paulina’s image serving as the sole reflection of Blackness in the entire story of Cuban Tampa. They are presented as simple folk who idolized and took care of Marti, although their actual contributions were more complex and important. They were part of a much larger group whose actions have been erased.

Tampa became a major fundraising and propagandizing hub, and Ybor City and a newer intensely Cuban section called West Tampa became prosperous enclaves. Cigarmakers’ wages financed preparations for the Cuban rebellion during the 1890s and earlier. The Pedrosos purchased several lots, in addition to their boarding house. They and two other Black Cuban entrepreneurs made good profits from their investments, much of which was funneled into Cuba Libre. Cornelio Brito and Bruno Roig owned stores in Ybor City and were active in revolutionary organizations: both were members of the reception committee for Marti’s initial visit in November 1891 and officers in leading revolutionary clubs. Brito had come from Key West, where he met the Pedrosos and several other Black Cuban activists who later moved to Tampa.

Included among the group who migrated from Key West were several prolific Black Cuban writers and editors who founded, edited, and wrote for revolutionary publications locally and published articles and books in New York and elsewhere. Educational opportunities for Black Cubans in the nineteenth century were very limited. Most of the figures described below were remarkable autodidacts who learned to read and write with little formal assistance. Paulina Pedroso reportedly taught herself to read both print and music, although she is presented as illiterate.

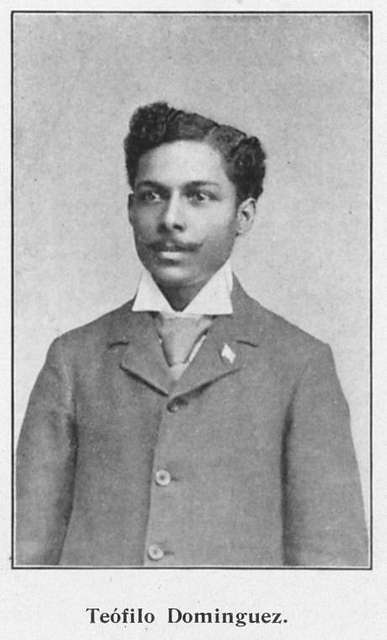

Cigarworkers informed and entertained themselves by hiring lectores who read to them in the large galleries where they worked. This practice fueled revolutionary writing and opened roles for at least six Black Cuban writers and editors in Tampa: Juan Bonilla, Teófilo Domínguez, Julián González, Joaquín Granados, Emilio Planas, and Francisco Segura. During the 1890s they founded or wrote for major propaganda organs in Tampa and Havana. Domínguez and González directed publications about sports, the proceeds of which were donated to the revolution. Segura and González were close associates of the PRC leaders in Tampa and wrote for the official publication Cuba. Planas founded a weekly publication, El Patriota, reportedly popular with readers and workers in the factories. Bonilla and González wrote for him and many other papers. Granados was also a prolific writer, a son of enslaved people who taught himself to read. He was associated with Martín Morúa Delgado, who lived in Tampa prior to the war and later rose in Cuban politics. All were close to Rafael Serra, a famous Black Cuban writer and organizer in New York. Domínguez compiled a book about their work, Figuras y Figuritas (1899), the only reason we know about them.

The war’s end changed everything. Most of the writers went back to Cuba. Brito gave all his wealth to the revolution after Martí’s death and left to join the fight, remaining in Cuba and dying there in poverty. The Pedrosos, who had given so generously, also died poor in a Cuba that was far less liberated than they had hoped.

Domínguez and Roig remained in Tampa, along with the Pedrosos, who initially stayed. They were among the founders who met in October 1900 in Pedroso’s parlor and started a club, La Sociedad Martí-Maceo, which would serve the next five generations. In 1899, Cubans in Ybor had formed a racially integrated mutual aid society, El Club Nacional Cubano. This was an era of intense Jim Crow racism, infecting Cuba as well as Tampa. The new Cuban organization lasted only one year. In events that went unrecorded, there was a split; Black members were ejected. Their response was to form a new Black organization named for celebrated Black and White Cuban independence heroes, perhaps a poke at former comrades. The Martí-Maceo Society became both haven and ghetto, a place to gather that also provided medical benefits and served the members well. Yet they all still suffered under Jim Crow.

Urban renewal projects demolished their building in 1965, so they moved to another less grand structure and managed to continue. Ybor City’s centennial in 1986 inspired a campaign to revitalize the area, still scarred by urban renewal. Developers sought to capitalize on Latin heritage and local history. Publicity and planning conspicuously left out Marti-Maceo, although the four White immigrant societies were prominently involved. This omission was consistent with long-held practices, but members objected this time in fear of another demolition. They recruited Susan to help them present and validate their history and forebears’ contributions.

Members gathered documents, photos, and elders to interview. A lovely pictorial history was created. We spoke at events and clearly established the historic importance of Martí-Maceo. It hardly mattered. Ten copies were donated to the Ybor Museum; an intern there told us they threw them away. Articles in local newspapers usually leave Martí-Maceo off the list of Ybor societies, still happening in 2021. Several years ago, members were granted an official historic marker outside their building. The marker disappeared one night, not long after a large decorative arch was installed across the intersection next to their building. The marker was later discovered hidden in a garage belonging to the city administration. No apologies or explanations, but they reinstalled it. Efforts to remove the marker were emblematic of the long-standing pretense that Martí-Maceo and its Black Cuban members never existed, that Ybor City’s history was White. Black Cubans made important contributions to that history, made sacrifices that were never repaid. Their descendants have made important contributions also, yet Florida’s K-12 teachers are now forbidden to teach about racism or the true history of the places where they live. Although the marker went back up, the erasure continues.