Article begins

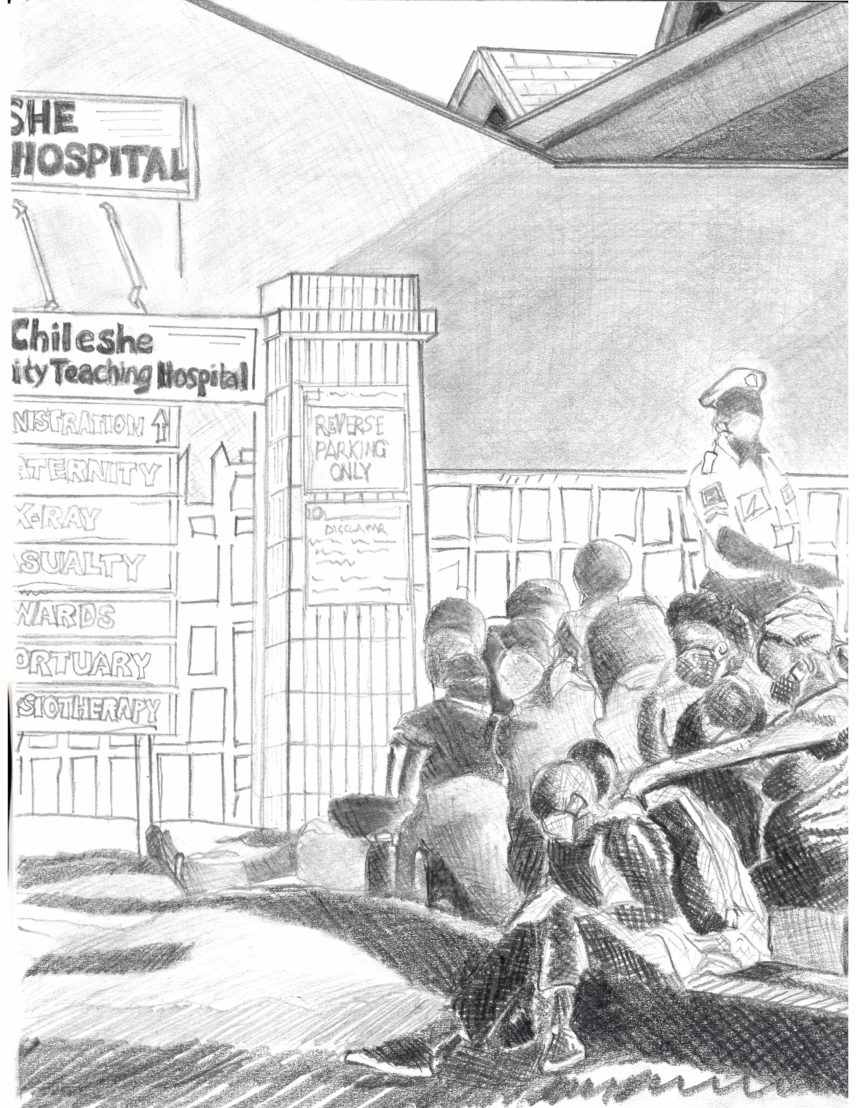

An iron gate marks the entrance to the first children’s hospital in Zambia. Pre-COVID, this gate provided an open entry and exit for patients, families, government officials, nongovernmental organization workers, and researchers. Now, the gate is no longer so porous: protocols designed to protect staff, children, and communities outside the hospital dictate who comes in, who stays in, and who must wait at the gate. One of the new pandemic rules is that visitors are not allowed in the hospital. Family and friends pass food, clothing, and messages through the gate to primary caregivers, often mothers, who reside in the hospital with the patients.

In August 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, we initiated our Caring for Caregivers study in the hospital. Only one of our team, Comfort (a medical doctor), physically crossed through the gate to interview caregivers. She did so masked and at a distance from August until December 2020, when COVID-19 cases in Zambia were on the decline. The rest of us—Mutale, Sarah, and Jean—virtually crossed through the gate during phone and Zoom interviews with hospital staff. And Comfort stopped visiting, too, when cases sharply rose in the country in January 2021.

In Zambia, the practice of caring for one’s kin in the hospital is referred to as bedsiding. Bedsiding, as the name suggests, means being at the bedside of a patient: watching, playing, feeding, bathing, praying, and advocating. But bedsiding also entails care away from the bedside, both inside and outside the hospital gates: washing laundry, cooking food, donating blood at outside facilities, collecting medicine from stores in town, and asking kin and friends for money for treatments. The hospital gate and its closure reveals care given, care received, and care needed.

Since we pitched this story, our founding team member, Mutale Chileshe, has died. This was a hard article to write, and what we write below may be hard to read.

Closing the gate

In October 2020, I (Comfort) approached the children’s hospital gates. It was visiting hour, a time when the gate was predictably crowded. I waited when I noticed a man approaching the guard. His hands were full. Through my mask, I could smell freshly cooked nshima and kapenta. I watched the guard nod to him; she recognized him and raised her phone to call up to the ward. I pictured a nurse answering the guard’s call and telling his wife or sister to meet him at the gate. The man nodded back to the guard and moved to the side of the gate to wait with others.

Hospital gates have always been remarkable. At hospital gates in Zambia, emergencies become evident, people meet, gossip is spread, help is given, and guards keep watch. But for more than a year, gates at hospitals around Zambia have been closed. At the children’s hospital, only one adult is allowed in with hospitalized children and fewer families are coming for care.

The gates open for staff, of course. When we asked how it felt to cross through, staff described fear. To enter the hospital at the peak of the pandemic, one staff member said, felt “like suicide.” But staff entered because this is what they do—they care for sick children, and it wasn’t the first time that they were encountering infectious conditions in their work. They keep going, they said, because of a “heart for the work,” a sentiment anthropologist Claire Wendland (2010) has discussed in depth in her work with medical students in Malawi.

The effects of lowered admission and fewer visitors are complex. Doctors and nurses worried: Were children getting sicker or dying at home? They had some evidence of the effects of delayed admittance when seeing children in critical condition once inside the gate. Alternatively, fewer patients and visitors gave staff more time, and this time enabled them to provide more attentive care to children who were present and also to the bedsiders too. This is no pandemic silver lining. That staff found themselves better able to care speaks to the challenging conditions of care in under-resourced hospitals; nurses in pre-COVID times might have had as many as double the number of patients they had in 2020 and thus far in 2021.

Care without visitors inside

COVID-19 is taking a toll on bedsiders. The number of bedsiders asking for medical attention, we’re told, has risen substantially. While bedsiders have always been “patients,” Mutale frequently reminded our team, the visibility and rise in illness is indicative of a change in support that some bedsiders previously received during visiting hours. Sister Claudia (Sister refers to nurse in Zambia) explained, “What used to happen in the past is that the bedsider would have people from home visit them and bring food, refreshments. And so that aspect is not happening anymore…” Visiting hours persist but visitors are not allowed past the gate. Without these visits at the bedside, Sister Penelope told us, the work of bedsiding is complicated: “It’s difficult for our bedsiders. For example, they need to go out and get something for the patient, for themselves. They can’t necessarily leave the patient alone and go. So those visitors were like a point of contact for them with whom—uh, where they come in and bring something in for them.”

Pandemic-related restrictions on visitation also make for difficult medical care. Some drugs and equipment are in short supply in Zambian hospitals, and clinicians may ask bedsiders to procure prescribed drugs, equipment, and tests outside the hospital. As Dr. Sakala explained:

But with COVID, [this necessity] has been a challenge… So if you ask them to go look for a drug, who will remain with the patient? If you ask them to go look for money to do the test, who will remain with the patient? So [clinicians] are not getting that much support from the bedsiders because of the restrictions on the number of bedsiders.

Care at the gate

In November 2020, Mutale, visiting briefly from Lusaka, and Comfort sat down at the gate to talk with the guards charged with gatekeeping. Emotions run high at the gate, the guards said, as parents and other kin and friends long to see a sick child and assist with caregiving. Sister Mercy explained, “Now with this same COVID when you stop them, you find that you start arguing [with visitors]. Yes, we are trying to protect the life of the visitor, the life of the baby, and the life of the mother… It’s better [bedsiders] receive them from outside rather than making congestion inside.” There are times when people sneak or make their way in through force or privilege. Nurses and doctors, then, act as gatekeepers inside, managing their discomfort, fear, and exasperation when telling people to leave.

However, nurses and guards don’t just keep kin out, they also help kin give care at the gate. They relay messages and announce arrivals. Nurses watch over children when bedsiders go out to receive food, medicine, money, and well-wishes.

Prisca, who was in the hospital with her three-month-old, was kept well by her kin and friends at the gate. When she called her brother, he brought her medicine that the baby needed and that the hospital didn’t have, even though she wasn’t “sure how he got the money.” Her neighbors brought food to the gate and sometimes they would pass 10 kwacha through for diapers. As much as going down to the gate provided some relief to Prisca, she was lonely; she missed socializing and she missed her church, whose members likely would have visited in pre-pandemic times.

COVID-19 restrictions compound the challenges families face in giving care to and receiving care from a range of people during hospitalization.

Not all bedsiders had people who came to the gate, just as not all bedsiders had visitors pre-COVID. Purity was six months pregnant and bedsiding for her 10-year-old stepchild from her husband’s first marriage. She told Comfort that her role as the child’s bedsider was a source of gossip among family and friends. Why was she the one doing the bedsiding? people asked. She told Comfort that no one except for her husband had visited her at the gate. And she saw her “friends from the ward” receiving “food from home.” It hurt that the child’s family and her friends and family did not visit. To make up for this absence, her fellow bedsiders would sit down with her, and they “would eat the meal [they received from their visitors] together,” inviting her to partake in their kin’s efforts to care.

Purity explained to Comfort that she hadn’t left her stepson’s bedside in a week. She slept in a chair nearby, something that bedsiders had to do even pre-pandemic. She was exhausted. At six months pregnant, she could not pick up the child or take him to the toilet. She was arranging for her husband to “swap.” Bedsiders, like Purity, have always needed to get out of the gate, especially when they are sick or exhausted, and when those left at home also need care. Before the pandemic, swapping was negotiated within families and at the child’s bedside, as one set of family members would take over bedsiding and another would leave. People still negotiate swapping within their families, but now swapping requires other forms of communication, via cellphones and gate conversations. It also requires hospital permission. As one nurse told us, bedsiders need “a very good reason” to swap, a preventative measure to avoid transmission of COVID-19. Purity had a very good reason. She also had someone with whom to swap, something that not all bedsiders had during or before COVID-19. In our prior studies, we have witnessed how stressors in the hospital and at home could draw bedsiders outside the gate, especially bedsiders who did not receive visitors or who did not have kin to make up for their absences in the household and in their income (Chileshe 2021). They did so even as doctors and nurses tried to convince them to stay, though such convincing could not be compelling, as Mutale recently wrote, without resources and without an understanding of the social.

Jean has shown in her prior work with children caring for kin who had tuberculosis that even before COVID-19 the hospital gates were already closed to some members of society—to children—when family members were hospitalized or bedsiding (Hunleth 2019). Children had to engage their creativity to give care to those in the hospital and receive care back from the people inside, what she calls imaginal caring. They traveled to hospitals in their fantasies to give medicine or to pull patients out so that they could watch over them. The children worried that, in their absence, the patient they care for and about would be alone, and being alone—for numerous reasons—could lead to death. Their assessments were based on evidence they had accumulated, including knowledge of the shortages in hospitals that families have long had to make up. Their fantasies aimed to make up for these shortfalls, to uphold and nurture their relationships, knowing that relationships were what could make the difference between life and death, of themselves and of their patient.

Our team takes lessons from the children in Jean’s study. COVID-19 restrictions compound the challenges families face in giving care to and receiving care from a range of people during hospitalization. These challenges predate the current pandemic, and so too does the creativity—the lengths that families had to go—and the absences in resources and of kin that have left some bedsiders and some patients abandoned. The gates are now visible. COVID-19 brings to light just how critical bedsiders have been to facilitating hospital care and just how needed visitors are to the work of bedsiders and clinicians. Care at the gate is just one form of care that has emerged to make up for shortfalls as everyone now must embrace their imaginations and creativity to survive. But this form of care, too, has its limits, especially for the many bedsiders and children who come to the children’s hospital already experiencing multiple forms of oppression, and, as a result, may not even have care waiting for them outside the gate.

Remembering Mutale Chileshe

For months we remained researchers “outside of the gates,” distanced from being either bedsiders or patients. The nurses and doctors we interviewed reminded us that this is not how life works. They knew that today they might be medical professionals, but tomorrow they could be patients or bedsiders. Their knowledge comes from exposure to systematic injustices and persistent inequalities. The nurses’ and doctors’ words hit home for our team six months after we initiated our study.

In January 2021, COVID-19 was spreading swiftly through our social networks in Zambia, and our team started to witness the deaths of acquaintances, friends, and family members. Mutale, pregnant with her first child and staying in her house in Lusaka, began feeling ill. She tested for COVID-19, each rapid test returning negative. With measured relief, she told us that she thought she just had a bad flu.

A week passed, and she WhatsApped our team: “Hi I started the week with energy and fit but am down with fever and a terrible cough.” Because her COVID-19 and malaria tests were negative, she said, “I guess it’s just a fever that will pass.” Three days later she wrote to Jean: “Hello my dear friend, am still in a very bad state Just continue to pray for me.” She was later admitted to the hospital, her sister and husband keeping watch at her bedside. A final COVID-19 test returned positive, and she was moved to isolation. “It’s hard without a bedsider,” she WhatsApped Jean, “You can inform Sarah and Comfort.” The next day she wrote “Amen.”

On February 10, 2021, Mutale Chileshe, our friend, our mentor, and the person who drew each of us, and so many more, to focus on bedsiders, passed away. We will move your vision forward, Mutale. May your soul rest in eternal peace.

We use pseudonyms in this article for all interlocutors except the authors.

Paul L. Banda is an accomplished Zambian self-taught artist, scholar, and administrative professional. He received his MA in human resources management from Washington University in St. Louis in 2017 and is currently working on his DLA dissertation. He lives in Houston, Texas, and his paintings can be found at Componere Gallery in St. Louis, Missouri.