Article begins

Stuart Sones was awarded the 2022 Student Paper Award from the Middle East Section. In this piece, he summarizes his award-winning paper. Find out more about this annual award for undergraduate and graduate students and the submission process on the MES website.

Conspiracy theories boiled to the surface of mainstream American media amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, shedding light on the heightened distrust that had been long festering in a neoliberalizing media landscape of competing authorities and truths. As an undergraduate student trying to find something to write my thesis about within the confines of my home, I did as most people did: I watched YouTube.

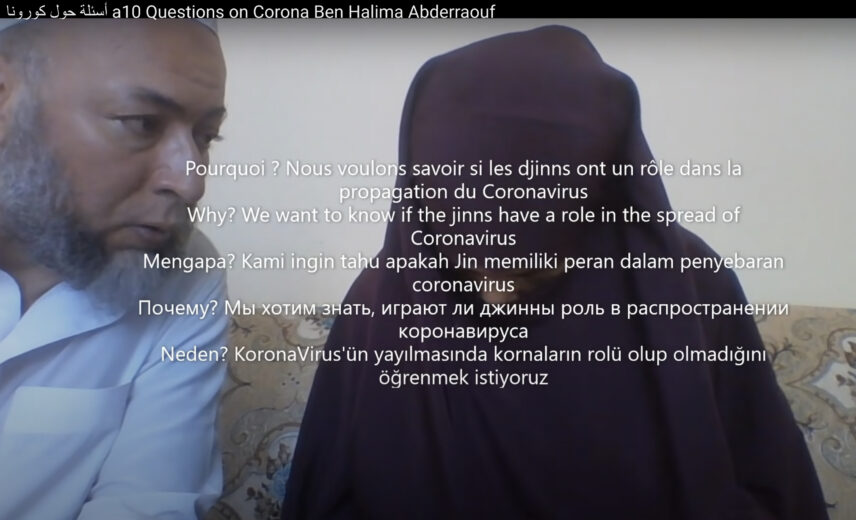

With the spread of the pandemic and quarantine’s effects on mental health, I became interested in understanding Islamic healing practices and began watching videos on Quranic cures for physical and spiritual maladies, a practice known as al-ruqya al-shar‘iyya. One title from February 2020 caught my attention: “Djinn Catching for Coronavirus, Ben Halima Abderraouf.” In the video, French-Tunisian internet preacher and traveling Islamic healer Abderraouf Ben Halima proposed a theory that I had not yet heard. Jinn (sing. jinni), the invisible beings who coinhabit the earth in the Islamic tradition, had colluded with the United States in planting the coronavirus in China.

Ben Halima’s video fused conspiratorial narratives with religious guidance, but what stood out to me was that he did not give a typical sermon drawing from the transmission of religious knowledge (naql) and reason (‘aql) to authenticate his claim. Rather, Ben Halima and a veiled woman beside him performed an elaborate routine known as “jinn catching” (khaṭf al-jinn) in which they invoked the jinn to convey the narrative as truth and impart a moral lesson. In the video, the healer recited the Qur’an over the woman (known as the “catcher”), summoning the jinn that would possess her. Once the jinn had fully seized the catcher’s body, he proceeded to interrogate them about their involvement in the pandemic. In a hushed growl, the jinn, speaking through the woman, revealed the invisible truths behind “hypervisible,” mediated politics. Concluding, Ben Halima reiterated the jinn’s discourse in his own words, urging Muslims to rekindle their faith and piously transform their community in hope of overcoming these malevolent forces and curing the anxieties that haunt Muslim communities.

Ben Halima, an unorthodox Islamic reformist at the fringe of contemporary Muslim practice online today can help us understand the making of religious authority and truth on social media platforms. With sites like YouTube crowded with influencers, internet personalities, and conspiracy theorists, traditional networks of trust have been disrupted, demanding innovative solutions for verifying the credibility of their claims. Ben Halima’s jinn catching answers this call. While not fitting the typical image of a digital nomad, the traveling Islamic healer’s performative techniques work to rationalize, authorize, and lend credence to his conspiratorial narratives within the Islamic tradition, all while making his brand of Islamic activism and neoliberal self marketable on social media.

Islamic entrepreneurialism in a moment of distrust

Abderraouf Ben Halima is first and foremost an Islamic entrepreneur. Born in Tunis in 1967, he excelled in mathematics before moving to France for university and beginning his career as an engineer. Involved in Islamic reformist da‘wa (proselytization) from the age of 15, he left his engineering job to commit himself full time to Islamic activism in 1995. He went on to receive a master’s degree in Arabic, which he used to start a French Islamic publishing company, Le Figuier (The Fig Tree). Through the company, Ben Halima has written, translated, and edited more than 21 books on various topics related to Islam (some of which are now available for purchase on Amazon).

Ben Halima was uninterested in the world of jinn until, as he narrates, jinn possessed his wife on a missionary trip to Pakistan in 1993, prompting him to seek a cure in ruqya, the liturgy of spiritual protection and healing based on the recitation of the Qur’an. By 1997, he had dedicated himself to treating people and training them across the Muslim world, establishing ruqya centers in numerous countries. Keeping pace with the digital platforms available to him, Ben Halima has amassed an international following, his website and videos available in seven languages. He is most famous for the “jinn-catching” method he pioneered to uncover invisible truths by mediating the voice of jinn for YouTube audiences.

But the healer, along with his trademark method of jinn catching, is by no means in the mainstream among the Muslim reformist circles to which he claims to belong. Echoing a tradition of skepticism toward the exploration of the unseen (al-ghayb), his reform-minded contemporaries have condemned his practices for being illegitimate and untrustworthy. For instance, the popular British preacher and ruqya-expert Abu Ibraheem Hussnayn claimed Ben Halima’s method violates the principle that “doubt does not take precedence over certainty.”

The critiques of Ben Halima’s engagement with the ambiguity of the unseen demonstrate the heightened skepticism that Muslim authorities and believers practice online today. As a result of media’s disruption of traditional centers of Islamic authority, the digital landscape has been flooded with preachers deemed either trustworthy or untrustworthy, whose self-branded, pious entrepreneurship is increasingly akin to the model of social media influencers. How then does Ben Halima prove to his followers that his version of the truth is reliable?

YouTube “jinn-catching” performances demonstrate the way in which neoliberal platforms have reshaped networks of trust in Muslim communities while generating novel methods for authenticating truths in this so-called post-truth world. Developing tools from linguistic anthropology, I analyze one of Ben Halima’s jinn-catching videos—this one about Saudi Arabia’s invitation of the controversial rapper Nicki Minaj to perform there in 2019—highlighting how his performative devices construct his authority and make his brand of ethical deliberation believable. Although Nicki Minaj ultimately cancelled her performance a week before the scheduled concert, this video nonetheless demonstrates how the decentralization of Islamic authority on social media has provoked new modes for certifying pious discourse amidst the increasing distrust that characterizes this hypermediated, neoliberal moment.

Catching jinn, authenticating conspiracy

Sitting in a Tunisian courtyard, Ben Halima begins his video by reading, with disdain, a summary of the news that Nicki Minaj had been invited to perform at the Jeddah World Fest. The invitation of a singer “who contradicts Islam” symbolized for Ben Halima the diminishing role that Saudi Arabia once played in reforming Islam and the weakening authority of traditional Islamic scholars: “This voice that called us to Islam,” he admits, “we no longer hear it.” He continues, “So, we will catch [the jinn] for all the viral, developed corruption in the Muslim community.” Ben Halima makes his intentions transparent, explaining that the purpose of the catching is twofold: First, to summon the jinn committing these sins and convert them to Islam. And second, to teach Muslims that there are those who conspire to destroy Islam, making it imperative for them to wake up from their negligence and revive their faith.

Turning to the woman beside him, he recites a supplication of sincere intention that ushers in a new generic frame and locates his performance within an Islamic paradigm. The expectations entailed in this framing device constitute a framework for entextualization, or the process of converting live performance into a standard, recognizable, and transmissible text. Such a process is vital for Ben Halima’s YouTube channel because it crystalizes his experimental jinn-catching performance as a reproducible act that he can sell online.

Next, Ben Halima recites the Qur’an to summon the jinn. The woman beside him begins to breathe heavily and make exaggerated gestures with her arms. With each verse Ben Halima recites, the possessed woman moves as if embodying the literal meaning of the text: for example, making a chopping motion with her hand as he recites Qur’an 21:30, a verse that depicts the splitting of the heavens and the earth. If listening to the Qur’an is a “moral physiology,” in which the believer must make themself an “instrument capable of resonating” the attitudes of the verses, then jinn catching takes this to another level as the catcher’s embodied performance enacts divine word through exaggerated corporeal signs. Through unsettling movements that convey her possession, the catcher gives affective and material force to the performance.

Soon enough, the jinn begin to whisper through the catcher’s body, revealing that satanic forces had tasked the jinn to corrupt Muslims by making a pact with Nicki Minaj. Ben Halima echoes back each of the jinn’s utterances, converting their otherworldly whispers into legitimate sources of knowledge. The act of echoing and amplifying the jinn’s speech is a “mediational routine,” a performance that entails the recontextualization of an utterance through a mediator to be heard by a new target audience—here the YouTube viewers—thereby authorizing the discourse.

As much as he reproduces the jinn’s whispers word for word, he does not replicate the discourse in form, accent, or pitch. He thus divorces the jinn’s utterance from its rhetorical power, rendering his own speech dominant over the jinn’s. For example, whereas the jinn speak in the Tunisian dialect, Ben Halima echoes in Modern Standard Arabic. While the shift in accent further legitimizes the jinn’s speech by making their language clear to a broader Arab audience, it also lends Ben Halima credibility as he speaks in an authoritative register closely associated with religious sermons. Moreover, he often gives the speech a sarcastic spin by raising his tone of voice and eyebrows. Such inflections decenter the authority of the jinn’s whispers in a way that allows Ben Halima to appropriate their power as authors of the speech and possessors of knowledge about the unseen. By imposing his voice over what the jinn convey in what linguistic anthropologists call “double voicing,” Ben Halima communicates his own intended meaning to the audience, facilitating the didactic purpose of the catching: transmitting knowledge about the unseen realm intended to motivate pious transformation.

The catching intensifies as Ben Halima recites more Qur’anic verses to summon stronger jinn, extract information from them, and ultimately convert them to Islam. But suddenly the jinn disappear. The camera refocuses on Ben Halima as he summarizes what the jinn had told him: “Thank God, you have all seen… Behind the singer’s performance are satanic jinn who want to spread corruption and humiliate Muslims.” With this evidence, he confidently imparts his pious guidance, imploring the Muslim community to embrace their faith: “We hope that, if we wake up and rise, repent for our sins, hold fast to religion and struggle, we will awaken Muslims and benefit them.”

While Ben Halima’s echo of the jinn’s speech may be thought of as a small-scale mediational routine, stepping back to look at the broader narrative arch of the performance from its introduction to its conclusion reveals that the jinn catching itself mediates Ben Halima’s original message. In his introduction, Ben Halima speculates that the Nicki Minaj scandal was in some way related to evil forces that wished to corrupt and undermine the Muslim community. The jinn then reproduce a similar narrative when prompted, Ben Halima’s words inhabiting the catcher’s body as much as the jinn. But their dramatic performance and elaborate story mask the relationship between their speech and Ben Halima’s, and even the topic of Nicki Minaj is all but lost (but somehow connected), causing the mediation to vanish. At the end, the healer emphasizes what he wishes to be the official narrative of the routine, indexing back to his original message but this time drawing evidence from what the jinn had revealed to authenticate his vision.

As such, Ben Halima’s jinn-catching routine becomes an ingenious empirical method for overcoming the heightened distrust within his community, proving certain truths about the precarious state of Muslims to YouTube audiences and imparting moral lessons to believers. The catching’s performative devices that mediate his message through the jinn establish Ben Halima’s authority as a credible Islamic preacher while making his self-branded content marketable, distinguishing him from the thousands of other contending voices online.

After watching my own country spiral into alternative realities in the wake of the pandemic and January 6 uprising, I began to see how authority and truth can be just as ambiguous as the world of jinn. As a healer, Ben Halima seems to be diagnosing the state of the world through his experimentations with the unseen, suggesting that the truth can be as difficult to pin down as jinn and just as difficult to certify.