Article begins

My Canadian passport and UK biometric residence permit are laid out on the kitchen table beside my laptop. Pages faceup, side by side. I line up these little artifacts of privilege ready for display. Two pieces of shiny laminated government paper presented to quickly construct trust.

The purpose of this call is to verify that the physical copies of my ID match the documentation I uploaded in the interview screening process. The check is only scheduled for 15 minutes; one last step of digital authentication. I don’t know yet that it will barely last 7 minutes, far from the time needed to demonstrate my skills or perform the institutionalized rituals of modern job hiring.

The browser window to the video call opens wider on my laptop screen. As the conference call starts, I briefly introduce myself to the two HR representatives and proceed to hold my ID card next to my face so they can check the black and white photograph. I’m aware that my passport photo looks much nicer than the hologram image on my residence permit. Then again, I was six years younger in the passport photograph and I’ve already distracted myself before I hear the words, “That’s great. If you could just hold it a bit closer to the screen. Excellent, thank you. That’s all from us. Have a great day!”

And just like that the appointment has ended.

Speak to someone working in IT and they will likely tell you that “digital authentication” refers to usernames, one-time passwords (OTPs), digital certificates, CAPTCHAs (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart), and multifactor authentication systems (MFAs). Speak to someone at an advertising agency and you may hear how “digital authenticity” is tied to strategic brand marketing and weaving a connecting thread throughout a company’s digital footprint. My participation in a series of interviews in different contexts has led me to question the process of rehearsing, evaluating, improvising, and familiarizing myself with my own version (and others’ versions) of a digital authentic self.

What does it mean to trust one another in an online interview? Body language experts might have certain takes on what to look for but decoding digital authenticity may be more of an art than a science. In an online interview, our identities are constantly negotiated and renegotiated as we communicate through our words, tones, and actions. Which elements offer a sense of digital authenticity? What do we possibly convey about our nondigital selves in this virtual arena, through the shared exchange of visual data and the transaction of words?

Improvisation

After a few minutes’ wait, I am admitted to the virtual meeting room. My eyes dart to the bottom right corner of my screen. 8:04 p.m., so we’re starting a bit late. It’s those two seconds of waiting for the browser to fully load that makes me feel helpless, as if my computer is about to crash. It’s happened before in an interview—an experience that left me frantic and frazzled.

The woman on-screen smiles pleasantly. She’s seated in front of a blank blue wall with the sun shining through a window to her left. I assume she is reading another computer monitor as her eyes are fixed on some object at the exact same level as the camera. She barely tilts her head to look at me and say, “Hello.” But then she pauses.

“Hi, nice to meet you,” I reply, and wait for her to continue. Naturally, I expect that she will start us off with an introduction or background information—the customary formalities at the start of an interview. When we continue to smile at each other, I take the pause as an opportunity to jump in and fill the silence: “Well, I know we have limited time for this conversation, so I’m happy to get started right away.”

Those magic words open a permission gate. She promptly begins, “Right. So, I’ve been having lots of trouble with my account, you see…”

This was an unexpected opening for a job interview, but I was trained to go with the flow. Interviews are about improvisation, are they not? My instinct is to go into researcher mode, encouraging and coaxing her to continue: “Alright. What are you interested in sharing?” Is this a surprise case study as part of the interview?

She proceeds to start sharing her screen explaining her difficulties navigating the conference and collaboration app, while losing track of attachments sent in various conversations. Suddenly its periwinkle hue is splashed across the shared screen with emails, conversation threads—surely confidential file names—listed. I try to avert my eyes and blur my focus. By now I’m sure my eyebrows have furrowed a little and my positive go-with-the-flow demeanour is wavering.

This cannot possibly be the start of my job interview, can it? I know I am improvising, but I don’t know if she is yet or not. I’ll just have to continue and see.

Familiarization

It’s a quiet Thursday morning in Amsterdam. I’m seated at my student residence standard-issue desk in one of the most basic swivel chairs imaginable. It’s a good thing I’m petite. My back aches from just thinking about my six-foot neighbor hunched over in his identical chair.

I comb through my inbox on my laptop, including a fresh email from a researcher who is writing a book. We sat down for the video call some months ago, and she has just sent me the transcript to review in preparation for our next interview. The email reads, “I’ve annotated, highlighted, and reviewed your original transcript of IDI-1—fantastic, insightful, articulate. Then I added a few illustrations from your notebooks. If possible, can we use this original IDI as a springboard to a second interview?”

Flattery immediately washes over me. There’s no doubt in my mind to agree to a second session. I’m far too curious to see what richness might emerge. I enjoyed the process—picking out a pseudonym, answering the questions, coming up with answers—and knowing that was my task. Just that. It’s the first time I have participated in research like this for a fellow researcher. Being asked, instead of doing the asking. It’s relaxing. I get to experience the therapeutic nature of qualitative research by contemplating the stories we rarely have or make time for to resurface.

I read on as I sip my morning brew. Her instructions guide me towards the original transcript attached. “Note what is interesting to you. Note what in that original interview manifested or motivated the actual moving abroad to Amsterdam.”

I’m far too eager to come back to this later. The moment I open the file, my eyes jump to the first line of the transcript: “Researcher: It’s kind of unusual for a researcher to be interviewing a researcher, which is fascinating. I hope you’re going to enjoy it as much as I am. I was looking forward to this.”

It is indeed a rarity. I have only ever read through my own interviews or colleagues’ interviews at best. I’m typically listening to questions in my own voice, except this time it was the voice of the person answering that I recognized in the transcript notes. A new moment of familiar strange.

I reread her highlighted notes in yellow: the lines that jumped out to her the most. I’ve picked fluorescent blue as the colour I will use to track my own curiosities, which I’ll eventually email back to her. I read on, familiarizing myself with what’s already been discussed and reflecting on new lines of inquiry that spring to mind. Key phrases and words jump out, but it is the surprise in my past self’s voice that entertains me.

Rehearsal

Rescheduling the interview for a second time would have been unprofessional at this point. Plus, a general hassle—or at least that is what I tell myself. Adina (a pseudonym) and I have both made time for this interview and the award selection committee needs to make a decision in the coming weeks.

Adina is from Romania and has never attended this specific North American research conference before, nor any for that matter. This award scholarship would sponsor her registration, flights, and accommodation to attend the conference later in the year. The procedure involves two selection committee members conducting an interview with each of our shortlisted candidates. Scheduling the interview itself required some extended communication to coordinate across three time zones and competing commitments.

Since it is my first time sitting on this conference scholarship committee, I’m hesitant on the best approach. Chitchatting with Adina is a polite way to stall to see if my co-interviewer will arrive. After several minutes, I make a snap decision to go ahead. I figure I will take a structured interview approach for the sake of candidate fairness. That way the committee can hardly claim I did the interview “wrong” if I simply read out the questions in a neutral, objective tone. Right?

I shift my comments and tone to some opening remarks and how the interview will proceed. Adina is eager to tell me about the research industry in Romania. Words flow out of her mouth in a stream, and she quickly begins to use her arms to capture the extent of her enthusiasm. Over time, her nerves begin to ease. I ask the next question. She answers. We repeat and 45 minutes flow by.

At the end of our hour, I ask Adina if there is anything we have not covered today that she feels is important for me and the rest of the award committee to know.

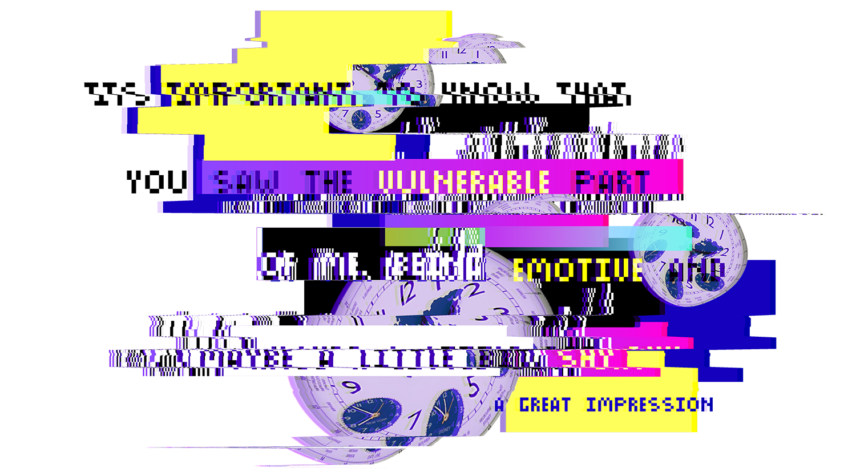

“It’s important to know that you saw the vulnerable part of me. Being emotive and maybe a little bit shy. When I am on the stage, when I am presenting, I am doing my homework. I am presenting in front of the mirror several times. So, I really manage to take this serious role so that the public cannot see my emotions and vulnerabilities. This is the part that you haven’t seen right now, and I feel that it’s important to know.”

I am caught off guard by Adina’s seeming desire to address her presentation of self and her sense of my impression. If anything struck me about her answer and delivery, it was her emotional willingness to discuss how research makes her feel inside. Yet openly admitting this would be far too encouraging since the rest of the committee needs to weigh in on this interview and the other candidates.

I smile and say, “Thank you, Adina. I think I have a great impression.”

Evaluation

Four of us sit around the boardroom table in a medium-sized meeting room, two on each side. The department head has set up the large screen so that the candidates’ full faces appear in the frame. Although, we each have our own laptops so that we appear evenly on the screen, which makes our facial features and expressions that much more visible. I expect it could be either a blessing or a curse to see our reactions up close, it just depends on the candidate.

We are gathered for the first round of interviews for an assistant professor. As a graduate student representative, I have every intention of performing my duties at the highest level of integrity and professionalism. This is a responsibility to my fellow students, future alumni, and to myself.

I try to maintain a resting, calm smile while on camera. I am silently embarrassed by how many times I make eye contact with my on-screen self. I type my notes for later consideration and chime in to ask my two questions without sounding robotic.

As we end the final interview, we launch into a brief conversation about the candidates. The discussion meanders to our inclinations to invite candidates to the next round despite any hesitations. A line of conversation creeps in around what candidates did and did not say. Phrases such as “face value” or “authenticity” cause me to squint a bit more in thoughtful consideration.

Committee members reach out for a second round of biscuits on the table, but the teacups grow cold. The pace of conversation has slowed down after more than four hours together. I am waiting for a signal that it is time to pack up and call it a day; but in the customary way I adopted during my fieldwork, I wait until someone else makes the first move.

Someone strikes up a final attempt to discuss immediate action steps that will hold us accountable. Papers are shuffled into a single pile, laptops closed, and notebooks shut. I take stock of all the hundreds of different body language cues from my colleagues as we pack our bags, agreeing to meet online to make our decision in a few days’ time. I notice which professors have polished nails, what colored pens they use in their notebooks, who has made use of the printer. Are any of these observations helpful for the task at hand? Probably not, but it does not stop me from making them anyway.

Applied anthropologists are asked to move so seamlessly in and out of the virtual setting of the online interview with its intimate, controlled format framed and mediated by the screen. A sort of neutral territory perhaps. We see what the screen shares, peripheral distractions and sensory signals—faraway gazes, fidgeting fingers, tapping feet—minimized.

In research and in work, applied anthropologists frequently make decisions based on the outcomes of online interviews. Video calls have become a comfortable medium to gather information to answer a variety of questions. Whether synthesizing important data, designing new services, bestowing a job offer, or awarding a scholarship, consequential decisions can hinge on these types of conversations. In these interactions, an evaluation is at hand to distinguish and appraise nuances related to consistency and genuineness—to elicit or decipher a kind of authentic response. Naturally, we want to have confidence in our informational exchanges, to leave with a belief that there is substance behind what was discussed and disclosed. We seek authenticity to convince ourselves that what we see and hear online genuinely represents either someone else’s, or even our own, true character.

Digital authenticity could be seen as the accumulation of actions and expressions used in pursuit of trust or genuineness or credibility. Yet there is no universal guide for what social cues and bodily signals might indicate one’s trustworthiness in a digital setting vis-à-vis in-person interaction. Instead, we must rely on the limited sensory information available to us in the moment.

What is “authentic” or “inauthentic” in such virtual spaces? We sit in front of the webcam asking those on the other “side” for honesty, while potentially judging what our ears and eyes tell us. We make this social contract from the moment we click “join” until the browser closes. And in the time that lapses in between, we adhere to performative roles that will keep us close to our desired outcome—an answer rich in detail, a seemingly candid disclosure of information, experience, or thought.

We may try to convey trust by responding to the tone of a comment or interview question, even when the flow is unexpected. Is the epitome of digital authenticity to replicate the same response as one would have off-screen? Or is the accidental goal to find yourself in an unscripted scenario—impossible to prepare for—so that you catch yourself behaving in a believably raw and unfiltered manner? Often, we value spontaneity as something akin to openness and vulnerability. But for stories to float to the surface, we must refresh them in our sea of memories and give ourselves time to contemplate. In the words of author and researcher Brené Brown, “Vulnerability is the first thing I look for in you and the last thing I’m willing to show you.” Therefore, we must guard against the belief that to be premeditated automatically equates to being fake.

Digital authenticity becomes a variant of sociologist Erving Goffman’s presentation of self, the ways in which people try to manage and control the impressions others might make of them while also trying to acquire information about the person or people they are interacting with. In the digital age, many of us are skilled at manipulating and controlling the information about us that people can access online, and, by extension, their opinions of us too. In online interviews, we gear up for an impression to be formed or a decision to be made and aim to elicit a positive reception.

How can I be honest in representing myself and my values? How do I show that how I am seen onscreen reflects who I am in person? How much doubt surrounding these pieces of information are valuable when we weigh our final decisions?

As applied anthropologists, we bring a hunger for honesty and truth into our work and our research that makes the very nature of questioning what social cues constitute “digital authentic” selves a reflexive task. If we are serious about questioning the authenticity of others, surely we must start to question our own too. If the best possible version is to mimic and transmit the same bodily, emotional, and mental responses as one would in person, the problem becomes less about how we perform in front of the camera, and more about how we exert ourselves in spaces where we lack so many of the sensory signals that inform our impressions and experience off-screen. We check our webcam preview, we click “join,” and we try to interpret words, tone of voice, and bodily expressions.

The need for digital authenticity vanishes if we relinquish the need for an evaluative framework and accept everything as honest and trustworthy. Then, the tension between actively monitoring and measuring the differences that may exist between one’s digital and nondigital self and simply ignoring any possible dissimilarities would be diffused. Except, would such a route diminish our ethnographic credibility in distinguishing this type of authenticity overall? What if we could escape the act of decoding digital authenticity altogether?

Illustrator bio: An Pan is a multimedia designer, illustrator, and culture lover. He is currently a designer-accessory to Chinese consumerism but works with a big dream of decolonizing design. He enjoys traveling and doll collecting.