Article begins

In July 2020, Alexei Dymdymarchenko, Lyosha or Dym-Dym to his friends, an artist whose work I had been following, died of complications from the COVID-19 virus in St. Petersburg, Russia. His death, devastating for his community, is too easily characterized as one death among many stalking adults living in long-term care facilities. The pandemic has accelerated the slow emergency of disability incarceration affecting communities across the world. Anthropologists in Russia studying the question of deinstitutionalization are finding that the pandemic has shifted the possibilities for redesigning social care in postsocialism.

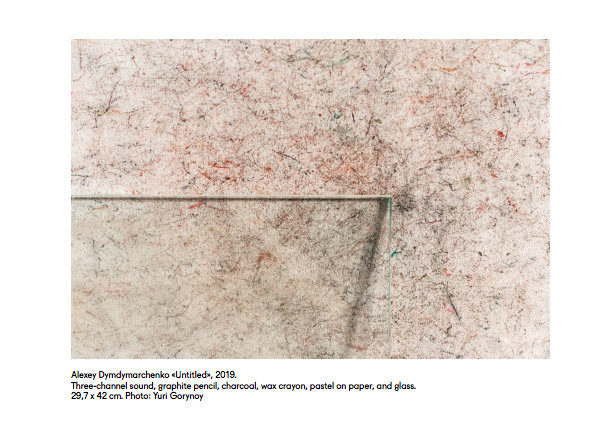

I learned of Dymdymarchenko’s artwork when I wrote to Sasha Ivanov, a curator and art studio manager in St. Petersburg, asking for samples of works by artists with disabilities for a gallery show in Toronto. I was immediately taken with Dymdymarchenko’s works. Untitled, they are typically an amalgam of seemingly random marks on the blank rectangles or European standard printer paper sizes. Ivanov described the work as “somewhere between sound art and performative practice” in a write-up for the international media art festival CYFEST, where the works were exhibited. Dymdymarchenko created each work by taking a bin of pastels (or crayons) and dumping it out over the paper, repeatedly, ceremoniously, as a tactile, gestural, and auditory process. In this way, each paper is a trace left over from a ritual sound performance, evidence of the repeated sound: the rush of small objects falling onto paper on a wooden tabletop. Dymdymarchenko himself was minimally verbal, and Ivanov typically represents him and other artists in the studio to the broader public. The studio itself is a program run by a nonprofit organization and housed in a small annex connected to a residential institution (called an internat in Russian) for adults with neurological and psychiatric disabilities near St. Petersburg.

I reached Ivanov via video chat for an interview about Dymdymarchenko’s passing and the broader impact of the pandemic on the studio community. Ivanov looked down for a moment, gathering his thoughts before describing Dymdymarchenko to me. He was, Ivanov recalled, light and willowy, tall and thin. He didn’t talk or hold conversations, but he had a unique kind of resolve and special focus and creative concentration in the studio that inspired others to consider their own work in new ways. He would sit quietly and turn the crayon bucket over, over and over again, with careful attention. And, his work was resistant to some of the common essentializing practices toward disability art that Ivanov finds frustrating, such as treating the artwork by disabled artists as “special” and apart from broader artistic conversations. To Ivanov, this way of siloing disability arts is paternalistic and bound up in the neoliberal production of value through inclusion, and does little to address underlying systemic ableism.

In the midst of the first few months of the quarantine imposed to tackle the spread of COVID-19, Ivanov explained, Dymdymarchenko ended up in one of the St. Petersburg city hospitals, one of two residents of his internat diagnosed with COVID-19. He was hospitalized for one month, and then returned to the internat. But he died of a heart attack soon after, a likely complication of the virus.

Receiving this news in Toronto, where the pandemic’s first and second waves swept nursing homes and residential institutions with devastating impact, I was struck by the cruel fact that Dymymarchenko’s death—as an Autistic adult living in a state-run institution—was profoundly unsurprising, even expected. His death reverberates with COVID-related deaths of others living in institutions in Russia, Canada, and around the world. As one woman with disabilities living in an institution in the United States told human rights interviewers, “people in institutions are not receiving adequate assistance or access to medical supplies. Staffing is insufficient and at dangerous levels.”

The moral calculus of determining how to prevent the spread of COVID-19 has consequences for particular communities, in this case the many adults diagnosed with intellectual and developmental disabilities, from autism to cerebral palsy, living in institutional care. Institutional care for disabled adults is typically contrasted with “community care”—the group home model that emerged in North America and Western Europe in the 1970s and onward, typically funded by government contracts and executed by nonprofit entities. While those nations juggle the challenges of community care, state-run institutional care persists in postsocialist Eurasia. The situation refracts an ongoing theme in ethnography of disability in the region: people with disabilities facing untenable situations that are at once uniquely post-Soviet in configuration, yet disturbingly quotidian in transnational disability advocacy. This theme is well established in anthropologist Sarah Phillip’s academic work on mobility disability in Ukraine, as well as in a both Russophone and anglophone works by the Russian sociologist Elena Iarskaia-Smirnova and her students, including a landmark edited volume. Beyond Russia, the harsh realities of life in institutional care across regions and cultural contexts have been well documented; ethnographers of disability experience have also attended to the resilient ways in which adults living in institutional and community care settings claim agency, pleasure, and a sense of self.

Institutional life for adults with disabilities in post-Soviet Russia and its alternatives is the subject of several recent works from medical anthropologists working in Russia. In her work on disabled residents and nondisabled volunteers in a St Petersburg area internat, anthropologist Anna Klepikova argues that disabled residents of these institutions claim agency in a highly regimented system that limits personal freedom of movement, media consumption, communication with others, and ownership of objects. Klepikova (in her monograph, published in Russian in 2018 and a 2011 article) explains that while the long-term staff attendants in the internats are paid poverty wages by the government, much of the day-to-day care is carried out by volunteers, usually young people from Eastern and Western Europe who have taken a sort of gap year volunteer position. These volunteers enter the institution in an unusual space of neither staff nor resident, and are therefore able to form more meaningful relationships with the residents than staff, who must maintain nearly impossible schedules.

However, not all people with disabilities in Russia live in institutions. My research on adults with disabilities living at home traces the nongovernmental organization (NGO) and government disability services serving that population, and a recent ethnographic film by Anna Altukhova (with Klepikova and Ilya Utekhin) documents the experiences of neurodiverse adult “graduates” of an orphanage system navigating personal agency in support of a living group home model in a rural Russian town; Altukhova also develops a theory of how psychiatric diagnosis and institutionalization in Russia reproduce social normalcy in a 2018 article (in Russian).

When quarantine began in March 2020, the staff of the nonprofit serving the institution where Didimarchenko lived, including those working in the art studio, undertook what was at first a last-ditch emergency effort to move some of the residents out of the internat to live in apartments in the city (including staff members’ own apartments and apartments of family members). Subsequently, with the support of several other NGOs, the organization undertook what they dubbed the Evacuation Project. Twenty-six residents from the internat (15 of whom participate in the art studio, of approximately 1,100 total internat residents) were relocated to apartments in the city. Others were able to go with family members who thought they would be more protected from the virus at home than in the internat. “Of course it’s dangerous in the internat, because the attendants who work there are taking public transit to get to and from work,” Ivanov told me, in Russian. However, the volunteers were not able to move Dymdymarchenko to a city apartment.

Those who stayed in the internat during quarantine experienced a tightening of the already strict rules: people weren’t allowed to visit other wards or rooms, there were restrictions on going to the art studio, the studio staff was forbidden from entering the internat building and could only go into the studio through the separate entrance. Meanwhile, the internat residents who moved to volunteers’ apartments in the city took to meeting on Skype. Volunteers have tried to support efforts to keep up communication between friends who are in and out of the institution, made difficult by limited access to technology for those quarantining in the internat. One artist has created an epic new work, covering the walls of their apartment room with colorful drawings.

Local histories combine with changing transnational “inclusion” models to create unique formations for living disability otherwise

For those who have remained in the institution throughout the quarantine, Ivanov reports that there’s an odd element to the way that fear circulates there. Residents are disconnected from the daily news cycle, as only some have phones and radios. The lack of access to information, increased restrictions, and staff curtailing movement reminds some residents of the early post-Soviet period, when shortages were rampant. NGO workers worry that the already insufficient carework staffing levels have been reduced, potentially creating dangerous situations for residents who require ongoing care to prevent bedsores or maintain personal hygiene. In early 2021, Ivanov posted a Facebook elegy, remembering another member of the art studio and internat resident who died on January 10.

Through the grim first year of the pandemic, a few small glimmers of possibility have emerged from these dark times for the disability advocacy community in the St Petersburg region. In spring 2020, disability activist Ivan Bakaidov’s social media campaign #ButWeAreAlwaysAtHome (#АМыВсегдаДома) went viral on the Russian internet. The hashtag asserted that the problem of being quarantined and stuck at home is one that is all too familiar to people with mobility impairment disabilities living at home in the St. Petersburg area, given the inaccessibility of the city’s built environment. Ivanov is working with others in the NGO sector and beyond to build capacity for community-supported living in the St. Petersburg region.

As I and other ethnographers of disability in Russia have argued, local histories combine with changing transnational “inclusion” models to create unique formations for living disability otherwise. Like the repeated soft pattern of pastels or crayons hitting paper in Dymdymarchenko’s sound drawings, the St. Petersburg disability community witnessing institutional deaths during the global pandemic reverberates the slow emergency of care that is disability incarceration.

Sasha Ivanov and Anna Klepikova contributed information, fact-checking, and conceptual framing for this article.

Dymdymarchenko’s work will be shown as part of the #CripRitual art exhibition in Toronto in 2022.