Article begins

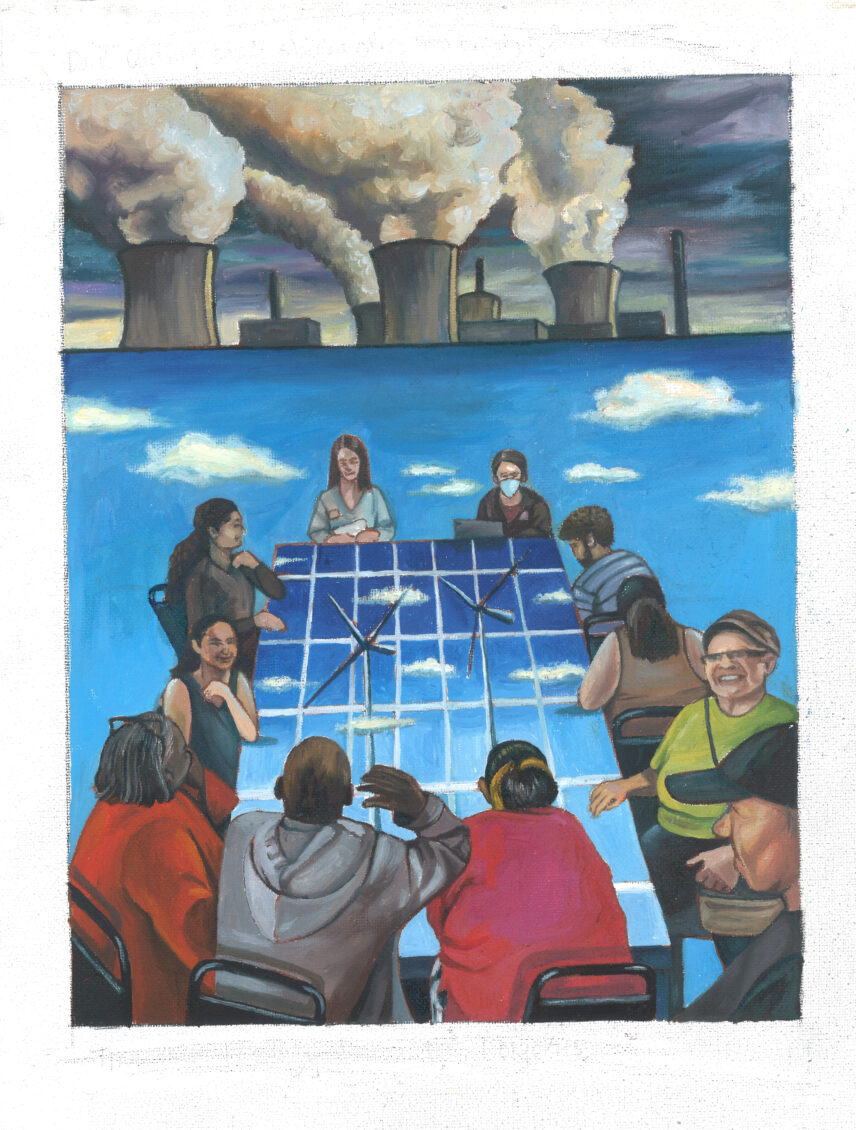

Energy justice sounds like the roar of dozens of people talking at once in El Mercado, the storefront event space of Nueva Esperanza, a community-service organization focused on supporting Puerto Rican and Afro-Caribbean people in Holyoke, Massachusetts. On a spring evening, El Mercado was the site of a focus group workshop intended to understand Holyokers’, especially Puerto Rican and Afro-Caribbean Holyokers’, desires and concerns about energy transitions from fossil fuels to renewable sources. Participants came prepared to share their energy-related experiences, opinions, and convictions.

Sasha: “If it’s [the energy transition] gonna affect the buses then I’m screwed because like, you know, I gotta take the bus. Or like cars, people can’t afford that. I tried to get an extra car and they’re expensive. Like, if they want to give us a new one, a FREE one…”

Kendra: “I’m the type of person—when I was a kid, my grandmother used to tell me, ‘If you’re done in a room, turn off the light.’ If you’re not using something, you unplug it. Yeah, cause no matter if you’re not using it, with it just plugged in, you’re still using electricity.”

Miriam: “Make it so that the families can afford it. Make it punctual, make it affordable. That way, you’re not going crazy trying to pay the bill, and you pay what is the price.”

Members of our community-based participatory research team of anthropologists, engineers, and community organizers heard these comments and much more that night. Neighbor to Neighbor Holyoke, the community organizers who collaborated with us to facilitate the El Mercado discussion, anticipated 20 or 30 people would attend. Our planning sessions centered on the ways that energy systems are essential to everyday life, but we thought convincing people to show up to discuss their ideas about these systems would be difficult. When almost 50 residents turned out for the workshop, it pushed against our assumption that people would not necessarily see their connections to highly technical aspects of energy infrastructures. Holyokers, we found, had plenty to say about their energy systems and possibilities for changing them.

Paper City

Holyoke, a small city of forty thousand people some 80 miles inland from Boston, is built on energy. Nicknamed “Paper City,” Holyoke was founded in the mid-nineteenth century as one of the first master-planned industrial cities in North America. Firms recruited immigrant workers to construct a stone dam across a narrow bend of the Connecticut River, with the dam feeding into a canal system powering paper and textile mills. People brought to Holyoke to construct the dam and labor in factories came first from Ireland, Germany, and French Canada, and later, from Puerto Rico. Industrial production continues today, often side-by-side with empty factory buildings. Like many former industrial centers across the United States, Holyoke has experienced patterns of disinvestment typical of late-twentieth-century offshoring practices.

Given elevated unemployment and neglected infrastructure in the city, Holyoke is prioritized for funding in federal climate legislation. State environmental justice statutes also prioritize Holyoke for energy transition funding due historical and ongoing inequities in exposure to environmental hazards at the intersections of race, ethnicity, language, and class. Fifty three percent of Holyokers identify as Latinx, more than 25 percent of residents live on incomes below the federal poverty line, and 22 percent of adults are considered English language learners. Among other hazards, aging housing stock located in proximity to waste transfer and industrial infrastructures subjects Holyokers to statistically greater burdens of lead poisoning and respiratory illness than the average Massachusetts resident.

Long before state-facilitated environmental justice protections, Holyokers took environmental justice campaigns into their own hands. Since the 1980s, diverse coalitions led by Latinx, especially Puerto Rican, activists have come together to successfully fight against proposed incinerators and gas pipelines. They have also organized for the creation of community gardens, renewable energy employment, and permanently affordable housing.

In 2014, Holyoke residents successfully organized for Holyoke Gas and Electric (HG&E), their municipal utility, to decommission their city’s coal-fired electricity plant and replace it with a combination of solar and battery storage. Coal plant workers were trained to support renewable energy infrastructures and employed at their same salaries. Member-organizers from Neighbor to Neighbor Holyoke played a key role in this early rehearsal of a just transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

To further support these efforts towards a renewable energy transition and gain new insights into energy justice issues at the community level, our team of researchers from the University of Massachusetts Energy Transition Institute (ETI) is collaborating with Neighbor to Neighbor Holyoke for community-based participatory research. Our goal is to learn from Holyokers’ experiences of their energy systems and to work towards improving the quality of life, housing, and urban environment in Holyoke.

The El Mercado gathering marked the start of an ongoing effort to place the desires of Holyoke residents, especially Latinx, Black, and working class Holyokers, at the center of renewable energy implementation in their city. With support from the US Environmental Protection Agency, researchers and organizers are codesigning a four-year series of citizen science research, technology workshops, and related activities that will engage Holyokers in developing just energy policies and practices. To facilitate a community-based and participatory process, we began with focus groups of Holyoke residents to situate ourselves within their knowledge of energy systems, the issues that are most salient to them, and their existing visions for just and sustainable energy systems.

Lived energy experiences

With simultaneous discussions around eight tables, El Mercado got loud. Snippets of parallel conversations in Spanish and English reverberated off brick walls and the metal ceiling. From the din, we could hear that people cared about energy in their homes and communities. Discussions that night converged around people’s worries about energy as well as hopes and ideas for change. Our participants did not speak in unison. Their voices mixed in overlapping and sometimes contradictory ways. Heard alongside each other, they sketched energy transitions and energy justice as multidimensional concerns.

Reflecting mainstream environmental movements, conversations around energy transitions in North America tend to over represent the positions of white, wealthy people. When communities of color, especially communities of Latinx, Black, and Indigenous people, are brought into these conversations, it is often to testify to violence they experience from fossil fuel infrastructures. Rather than centering damage, we hoped our focus group conversations could begin a process of supporting Holyokers in building an energy system that reflects their desires and values. We refined focus group questions through dialogue with city residents. What types of energy do they use at home? How do they interact with energy providers? How do they think transitions to renewable energy systems will affect them? What would make energy systems fair, especially for people in Holyoke?

Across workshop tables, people discussed frustrations with their energy system, especially its rising costs. The electricity rates charged by Holyoke’s energy provider, HG&E, a nonprofit utility owned by the City of Holyoke, are lower than those charged by for-profit utilities operating in adjacent towns. With two-thirds of the city’s power coming from municipally owned hydroelectric generation, the electricity supply is also one of cleanest in the Northeast. And yet, for many residents, especially those facing increasing rents, monthly bills are a source of stress. As one participant put it, “Your bill goes up a little and they’re quick to turn it off. […] Not everybody is sitting on racks of money, you know?” Unaffordable bills remained a concern, even for participants who had taken significant steps to reduce their energy consumption. Common strategies included minimally heating homes in winter and limiting air conditioning use to days when it was hotter than 90 degrees.

At one table, five Holyokers grappled with feeling a lack of control over their energy despite municipal ownership of their utility. Amelia, an artist in her 30s and a relative newcomer to Holyoke, moved discussion in this direction. Amelia and her partner owned their home. Unlike 60 percent of Holyokers, the pair did not need permission from a landlord before taking steps to conserve energy like adding insulation. But when looking for options to replace their aging, gas-powered boiler with an electric heat pump—a technological change that can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and energy costs—the couple found HG&E lacked basic guidance provided by neighboring utilities. Amelia explained that even though Holyokers technically owned HG&E, “It doesn’t feel like it’s ours.” Other participants added to Amelia’s comment, noting the barriers people faced in accessing public utility meetings. Even when people could attend meetings, they found surprisingly little discussion around utility rates and policies.

At another table, six Holyokers shared their excitement at the prospect of having new technologies in their homes that would reduce their energy use and improve their quality of life. Among them, Sasha, a Latina/e in her late thirties living in a public housing apartment building with her two children, chimed in, “I think we should have solar panels in each home. It would help reduce our dependence on traditional energy sources and lower our bills in the long run.” An older woman and longtime resident, Miriam, met Sasha’s optimism with a note of caution. Miriam also lived in public housing, and she was especially worried about the possible damage that solar installations might cause to roofs, resulting in the need for costly repairs: “Families need more financial assistance to ensure their homes are safe and comfortable.” The conversation turned to participants’ common desires for reducing fossil fuel dependency in ways that also reduced the costs of cooking, cleaning, and heating their homes.

A table of longtime Holyokers discussed their ideas for changes to make energy fairer for people in Holyoke. Teresa, a schoolteacher in her fifties, voiced her concern that new technologies rolled out in Holyoke would end up just like the solar hot water heaters that used to cover the roofs of her relatives’ houses in Puerto Rico. The devices were installed as part of island-wide energy conservation projects. For a while, they kept bills low while showers, baths, and taps ran hot. But when the devices stopped working, none of the specialized installers flown in years before were there to make repairs. Plumbers often replaced broken solar heaters with more readily available fossil fuel-powered ones. Around the table, other women nodded and expressed similar concerns.

After the formal end of the discussion, an elder named Donna wondered aloud, “But who’s going to help us? No one cares enough to help us!” Donna’s question encapsulated ones asked in discussions throughout the evening. People in Holyoke know well that climate change is a planetary problem to which not everyone contributes or experiences equally. Across contexts, wealthy institutions, corporations, and individuals benefit most from fossil fuel economies. Lower-income people, especially lower-income Black and Brown women in places like Holyoke, shoulder the overwhelming burden of environmental costs from fossil fuel extraction, production, and use. As Donna intimated, most people in the room understood the pressing need to phase out reliance on fossil fuels. Yet they also refused to take sole responsibility for addressing an unevenly distributed, collective problem.

Desiring energy justice

Engineering models and individual decision-making frameworks are helpful starting points to energy transitions. But they also reproduce faulty assumptions that energy users do not have adequate knowledge of their energy systems, especially in relation to fossil fuels. Energy realities are more complicated. The Holyoke residents who turned out for our workshop show how people often have intimate knowledge of energy and desire to phase out fossil fuels from their energy systems. Yet people face structural barriers to making that transition a reality. Those barriers cut across institutions, political economic systems, and built environments. People identified them in discussions around escalating bills, opaque utility operations, and roof conditions.

Holyokers centered the need for renewable energy transitions to address inequities that are endemic to fossil fuel capitalism. While people were interested in adding solar panels to roofs and swapping out old fossil-fueled heating, cooking, and cleaning systems for efficient, electrified options, they also worried that landlords would increase rents to cover new systems. Their worries reflect how the United States’ legal system is stacked against tenants across local, federal, and state registers. For instance, recently enacted energy transition policies focus on subsidizing building owners to phase out fossil fuel use, but do not protect tenants from displacement through environmental gentrification. Alongside this, some Holyokers observed how merely swapping in electrified options will not necessarily phase out fossil fuels for good. Sustaining energy transitions requires building capacity in local communities to repair systems when they inevitably break.

As participants mingled after the focus group conversations, they continued to ask questions like, “Well, what comes next?” This question had multiple meanings. For some, it was a request to know when members of our project team would report back on the overarching themes raised in the focus groups. Others wanted to discuss actionable steps their communities could take to make energy systems that reflect their shared values and priorities. Across these meanings, Holyokers conveyed a common commitment to engaging further around thorny issues and anxieties inherent to infrastructural change.

In a multiplicity of voices, Holyokers articulated how energy transitions link everyday experiences to structural concerns around racial equity, economic dignity, and sustainability. Listening to them, we heard desires for energy systems that can assure just futures. For our participants, a just energy system would make it possible for everyone to live in clean and comfortable homes without fearing shutoffs or unpayable bills. It is one in which utilities would set transparent policies and be accountable for phasing out fossil fuels. In the context of transitions from fossil fuels to renewable sources, Holyokers reflect how a just energy system must provide people with certainty that they can remain safely in their homes and communities over the long term.