Article begins

The unsettledness of our times fuels a deepening engagement between poetry (speaking as if speaking matters in shaping the world) and anthropology (knowing ourselves and our lives merely as one among many ways of being). This meeting place of poetry and anthropology—this ecotone, a region of transition between two ecological communities—bears special attention. Poetry attends to experience through living language, animates the present, and brings the full range of ourselves to our writing.

In The Day of Shelly’s Death: The Poetry and Ethnography of Death, Renato Rosaldo writes:

Poetic exploration resembles ethnographic inquiry in that insight emerges from specifics more than from generalizations. In neither case do concrete particulars illustrate an already formulated theory. In antropoesia, my term (in Spanish) for verse informed by an ethnographic sensibility, I strive for accuracy and engage in forms of inquiry where I am surprised by the unexpected. Antropoesia is a process of discovery more than a confirmation of what is already known. If one knows precisely where a poem is going before beginning to write there is no point in going further. The same can be said of thick description in ethnography where theory is to be discovered in the details.

Ethnographers and poets should both start from an understanding that we must attend to people’s experiences with dynamic awareness and living language.

William Carlos Williams wrote in “Asphodel”:

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

Recent poetry challenges Williams’s claim—our understandings of the world can be both informed in the ways of social sciences and transformed in the ways of poetry.

Poetry that speaks to anthropology

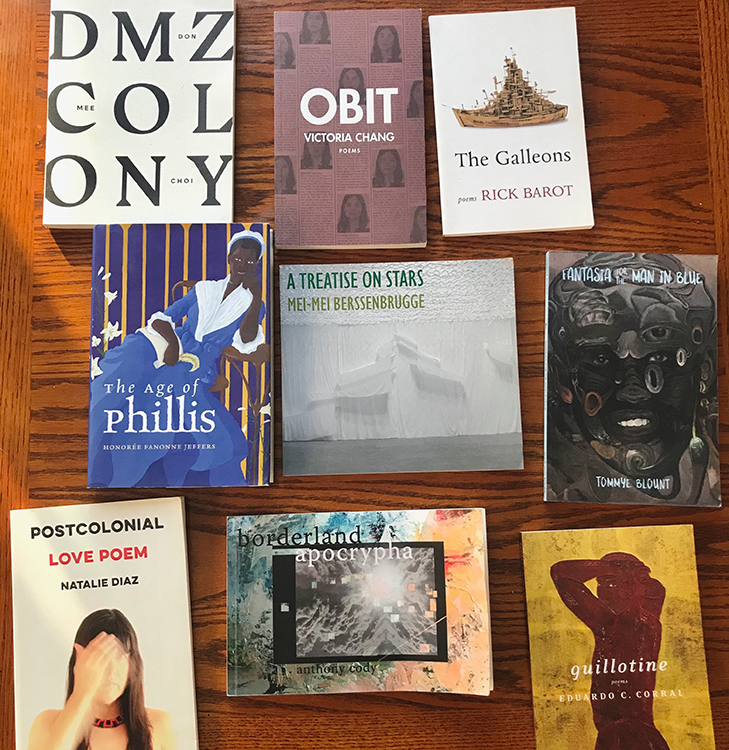

Consider the longlist for the 2020 National Book Award for Poetry. Ten powerful books, with poems exploring topics relevant to contemporary anthropology: racism and social justice, postcolonialism, political turmoil, death and its echoes for the living, love and passion, borders and history, animating the present with stories and thoughts of people whose lives have frequently been ignored and often actively destroyed by the powerful. Anthropologists sometimes talk about “giving voice to the voiceless,” but in our current moment of multiple social crises, the poets on this list provide their own voices. Our collective social imaginations will become more resilient in meeting the challenges of our times if we develop better deep listening to what these poets speak.

After I ordered the books on the list, I sat down first to read The Galleons by Rick Barot. I started at 9:30 one evening, and by the following morning had gulped the entire book. In “Marimar” (58 lines across three pages), Barot draws readers from the Spanish invasion, through phantasmagoria of the Catholic Church grinding beauty out of the poverty and struggles for self-identity it inflicted on Indigenous communities, through lingering traces of the past that underlie contemporary life. The poem begins:

One of the things I know

is that the most beautiful church in the world

is in the Philippines, in the province of Bohol,

in the town of Bacayon. Built in 1727

by Jesuits who must have believed

its jewel-box interior would subdue the natives

into belief, the church still strikes

each of us, jaded and tired from having seen

too much already, with the solemn hunger

that the place is supposed to stir.

Barot offers thickly described glimpses of parrots, pythons, and monkeys paraded for the gaze of tourists under the guidance of a drag performer in the identity of “Marimar,” whose green eye shadow “rhymes with the church’s crumbling.”

Another finalist, The Age of Phillis by Honorée Fannone Jeffers, provides a poetic archaeobiography of the life, writings, and death of early American poet Phillis Wheatley Peters. The age of Phillis is a long age, extending from Spanish ships sailing to the western hemisphere to the precise moment you are reading these words. Time does not move in a linear direction when it comes to considering how race, gender, and power shape US and global realities. Fannone Jeffers excavates not the past, but an alive and real present. The author summons voices through poems as lost letters to and from Phillis, blues performatively laid out on the page, choruses of “the mothers-griotte,” and more. Fannone Jeffers’s novel, The Love Songs of W. E. B. Du Bois was longlisted for the 2021 National Book Award for Fiction suggesting that hers is a voice to which we all need to listen, in whatever genre she writes.

Two other collections, Fantasia for the Man in Blue by Tommye Blount and Travesty Generator by Lillian-Yvonne Bertram, should be required reading for the moment we live within. Blount’s title poem brings us into the consciousness and body of a Black man confronted by authority simply for stepping outside. The poem begins:

You know good and well you can’t be out here

in the dark morning to take in

the moon—full as the bowl of light

attached to this police cruiser.

And concludes with an experience too well known by men with black skins in our racialized society:

don’t say anything else. Let me

take over this body; soften what letters

will bend—I am a poet after all.

Don’t worry. You’ll see. He’ll wish us

a good morning and let us go

after he bends us over the black hood.

We want Blount’s words in this poem to be true—we want the narrator to go home to coffee, to a good morning, to tell this as an anecdote at the end of white supremacy. And yet we know the world that does not force Black men’s bodies to bend is not yet born. Blount’s book offers a seed toward creating that more just world.

I partially grew up in the Texas borderlands, and I have worked in Latin America as a teacher and researcher. I am drawn to the work of several finalists (Eduardo Corral’s guillotine, Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem, and Anthony Cody’s borderland apocrypha) who write in the borderlands that are the subject of important, recent ethnographic work in anthropology (such as in Jason De León The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail). They offer experience-near insights that should make ethnographers pay attention.

Corral’s collection includes “Testaments Scratched into a Water Station Barrel,” a 20-page sequence witnessing the risks, hopes, sufferings, and material realities of humans driven to try crossing a deadly desert rather than stay where they are vulnerable to violence or harassed by poverty:

Bought my luck.

Rabbit’s foot.

Hiked through paloverde.

Thick heat.

Bullet holes in cacti.

Rested by a ditch.

Sand littered with used tampons.

Took off my sneakers.

Ants crisscrossed my feet.

Sandal straps.

Passed around crackers.

Tuna cans.

Mustard & ketchup packets.

Trekked over three hills.

Dashed across a dirt road.

Nearly stepped on a diamondback.

Quiet coil.

Squatted under mesquite.

Drank hot water.

Tried to forget the plazas of Hermosillo.

Rose bushes.

Roasted cashews.

Tried to remember my uncle’s phone number.

A butcher in Iowa.

Ames.

Walked toward a mountain.

Coolness felt through the heat.

Guillotine.

Meanwhile, Natalie Diaz’s work reminds us that borderlands are located not only at boundaries between nations. In “Manhattan is a Lenape Word,” she says:

Manhattan is a Lenape word.

Even a watch must be wound.

How can a century or a heart turn

If nobody asks, Where have all

The Natives gone?

Later in the poem, as “the only Native American / on the 8th floor of this hotel or any” in New York City, she observes:

Somewhere far from New York City,

an American drone finds then loves

a body—the radiant nectar it seeks

through great darkness—makes

a candle-hour of it, and burns

gently along it, like American touch,

an unbearable heat.

The poem ends with a moment of reflexivity:

The siren song returns to me,

I sing it across her throat: Am I

what I love? Is this the glittering world

I’ve been begging for?

The book that ultimately received the book award, DMZ Colony, fuses poetry, photographs, visual documents, and interviews—an approach that would be at home in any imaginatively constructed ethnography. Don Mee Choi, in her study of the after echoes of traumas of colonialism, war, and torture creates an exemplary multimodal text.

Poetry as a place for full-range anthropology

Anthropological writing can seem distant from our deepest experiences—poetry can point the way to bringing the full range of ourselves into what we write. This occurred for me in my own writing. In Places in the World a Person Could Walk, I turned to poetry to grapple with generational legacies of abusive men. Speaking in the voice of my father—who developed a self-aggrandizing persona partially in response to having been abused himself—I wrote, “My Father, Talking About Sausage”:

You can’t make sausage like I do.

Nobody can.

Not every piece of meat seasons the same.

You can’t cure it right.

You don’t know the things I do.

I’ve been blessed—a pinpoint tongue.

I taste everything, the seasonings.

I make the best sausage:

I’ve got the taste for it.

The most flavorful meat’s right here—

here where the arteries spread from the heart.

The poem ends:

My father, talking about sausage, alone,

as if he had made everything—the deer, the hog

and the life that goes into the making.

My second book, With the Saraguros, opens with a poem (“Advice to a Technopelli”) reflecting on methods of learning with community members. Among other advice (to myself and others seeking cross-cultural understanding) I wrote:

Bring everything inside you, not just your brain— and use it all, every day. You’re first human, traveler second.

In ecological science, as well as the applied practice of permaculture, “edge effect” refers to the way that ecotones sometimes result in richer biodiversity. This can certainly be beneficial when edges are the natural results of transitions between ecological systems. There is also a negative form of edge effect when habitats are disrupted (by clear cutting or other forms of upheaval). Species can become vulnerable in these circumstances, as conditions change rapidly.

In the case of anthropology and poetry, the benefits of exploring the ecotone are clear. Diverse voices, both for listening and for speaking, can bring more of what it means to be human into our work. Poetry and anthropology can and must talk to one another to build our human consciousness to be more than—more than what we think we know; more than what we assert to be true; more than the certitudes our discipline has claimed.