Article begins

The “Going Native” cartoon for this issue of Anthropology News was an exercise in celebration of the International Year of Indigenous Languages, personal discovery, and reverse linguistic imperialism. It is also an opportunity to highlight the discoveries that come from the collaborative aspect of much of my work in indigenous language vitality. I learned Maliseet as my first language but the American school system offered neither support for Maliseet language instruction nor accommodation. By the time I finished high school my primary language became English. My personal experience of grappling with linguistic imperialism includes traumatic episodes that I’ve shared elsewhere. For this celebration I focus on the creative energies that could serve as important catalysts for tipping endangered languages toward language life and vitality.

This issue’s cartoon required my close collaboration with a fluent speaker of Maliseet. I am re-acquiring Maliseet and I needed the help of an expert speaker. Allow me to introduce you to my mother, Henrietta Black. She is a respected Maliseet elder residing on Tobique First Nation, New Brunswick, Canada. She has the remarkable gift of being able to translate from English to Maliseet and Maliseet to English instantaneously, and she provided the Maliseet translation of my English text cartoon. She was patient with me as I worked through the translation, continually making grammatical and spelling errors as well as asking incessant questions about the semantic properties of Maliseet words. The following is a frame-by-frame representation of our creative process working from my initial English text sketch to the final Maliseet version—a celebration of emergent vitalities in collaborative indigenous language revitalization work.

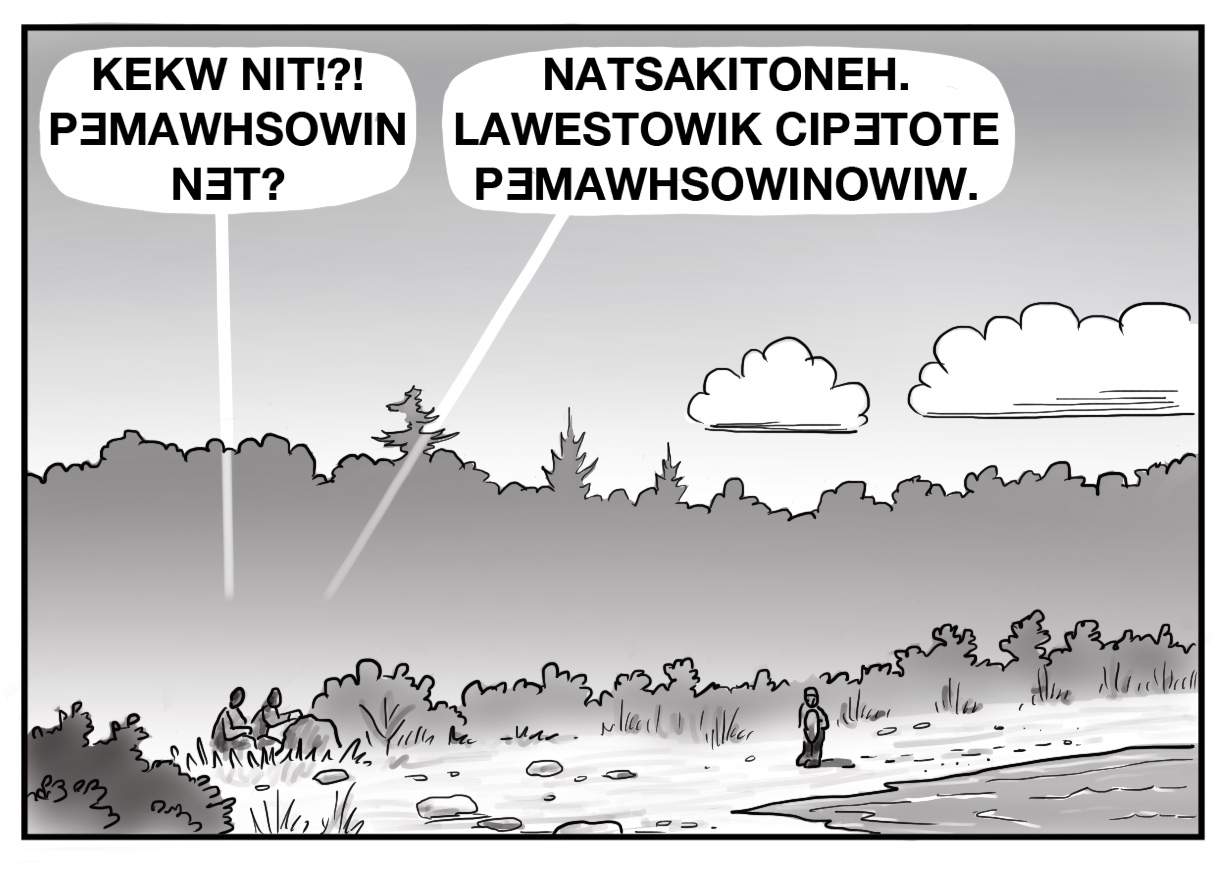

Have you ever wondered what the first peoples of native North America thought when they encountered Europeans for the first time? As a person indigenous to North America, I am reminded on a daily basis that linguistic imperialism is a reality I must endure my entire life. I have to learn foreign language place names, read maps inscribed with those names, and listen to stories that rewrite native lands into colonial places. The greatest and most painful erasure is the persistent silencing of indigenous voices. This cartoon became a way of imagining “in other words” the first moment of encounter between the native peoples on the Atlantic coast and the Viking explorers. So, I turned back the clock a thousand years to imagine what the first peoples of the Americas thought when they first saw strangers strolling on their beaches. Who were these strange creatures that waded ashore on native land? Were they human? As a member of the Wabanaki confederacy, the people of the dawn, I imagined walking along a familiar beach to see for the first time a Viking in full armor. It would be a strange sight. Despite the stranger, it is still my Wabanaki world. The familiarity of my world is punctuated by my encounter with the stranger who embodies the strangeness. The first frame sets up the encounter between Wabanaki worlds and Norse worlds. It also positions the reader/viewer to assume the indigenous perspective. How do these Wabanaki observers make sense of the anomalous apparition in their world? The first task is to recognize the stranger as “strange” and the second is to reconcile the foreignness of the anomaly within the Wabanaki world. The two Wabanaki humans posit the possibility of inclusion and acceptance.

In this first frame, as is typical for my mother, she translated without hesitation the English text as follows:

WHAT IS THAT? KEKW NIT!?!

IS IT HUMAN? PƎMAWHSOWIN NƎT?

I wanted to know more. How was the English word “human” translated? I had understood PƎMAWHSOWIN as a person. She glossed PƎMAWHSOWIN NƎT as “a living thing.” Wow! I have a whole lot more to learn about the semantic properties of Maliseet words.

During the translation for the second speaker’s text a couple of things came up.

LET’S CHECK. NATSAKITONEH.

IF IT HAS LANGUAGE IT MIGHT BE HUMAN. LAWESTOWIK CIPƎTOTE PƎMAWHSOWINOWIW.

How would one translate the English expression “let’s check” and the word “language”? My mother decided on NATSAKITONEH which translates as “let’s go see.” Instead of “language” my mother used LAWESTOWIK to indicate that “if it talks” it might be human. She decided to afford the stranger the possibility of speech rather the possession of language. She is thinking in Maliseet and I am stuck in English: to paraphrase E. E. Evans-Pritchard, I’ve been using English idioms so long that I think in those idioms. Damn! I’ve gone anthropologist!

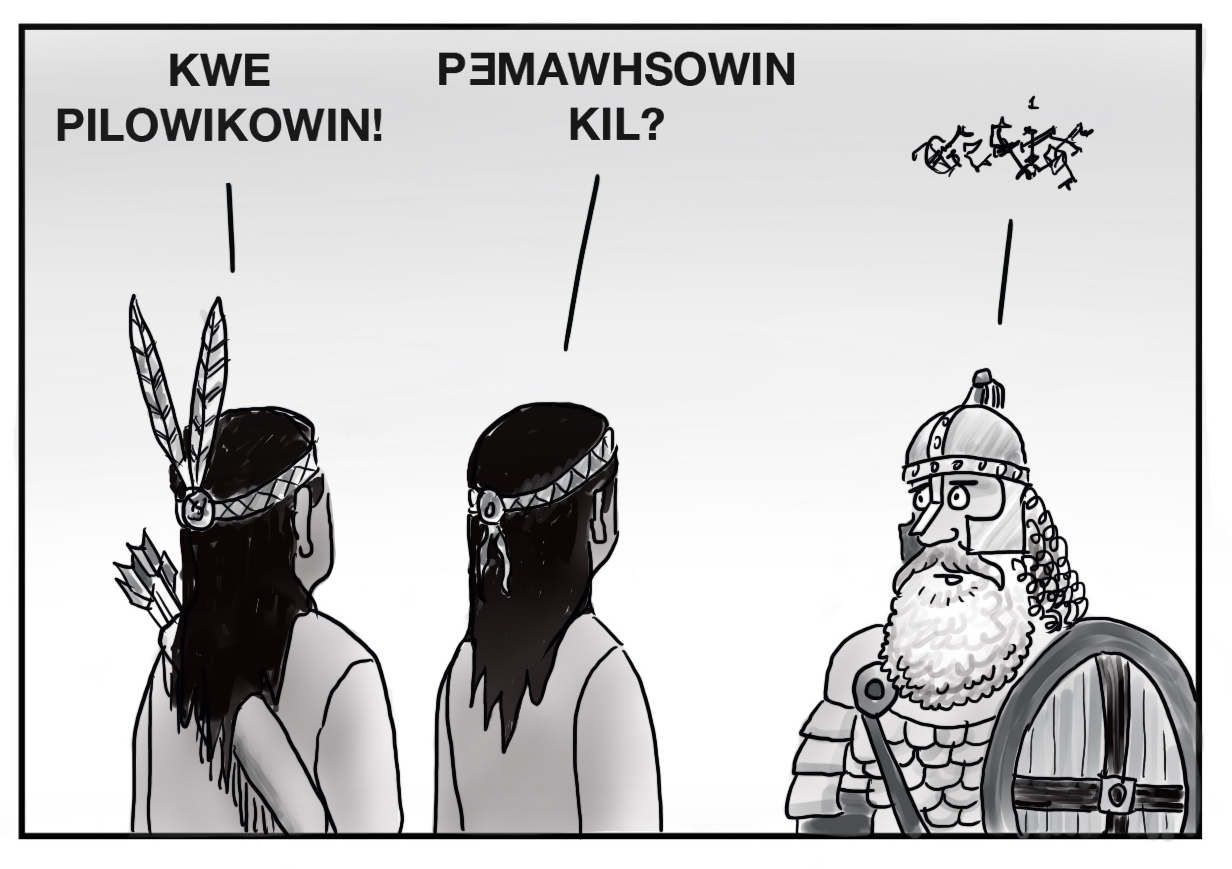

For the second frame I imagined indigenous openness to understanding the strange element as a seemingly novel but perhaps related entity in the Wabanaki world. All that is needed is confirmation. So, the two humans decide to test their hypothesis—the stranger might also be human. The reverse gaze allows me to remind all of us that every new encounter will entail mutual assessment of relationships and epistemes.

The second frame prompted a conversation about how to translate “greetings” and “stranger.”

HELLO STRANGER! KWE PILOWIKOWIN!

Though it is rarely used in everyday conversations, my mother and I know that KWE is sometimes used as “hello” and other similar greetings. As for “stranger,” my mother initially suggested wenoc (white man) but paused and decided on pilowikit (entity that is strange or different from us).

The second speaker presents the “human” conundrum again.

ARE YOU HUMAN? PƎMAWHSOWIN KIL?

I had the impression that PƎMAWHSOWIN was translated as “person,” but my mother described it as “living, breathing, human being.” In the space of two frames I grapple with PƎMAWHSOWIN going from “living thing” to “living, breathing, human being.” My path along semantic discovery continues.

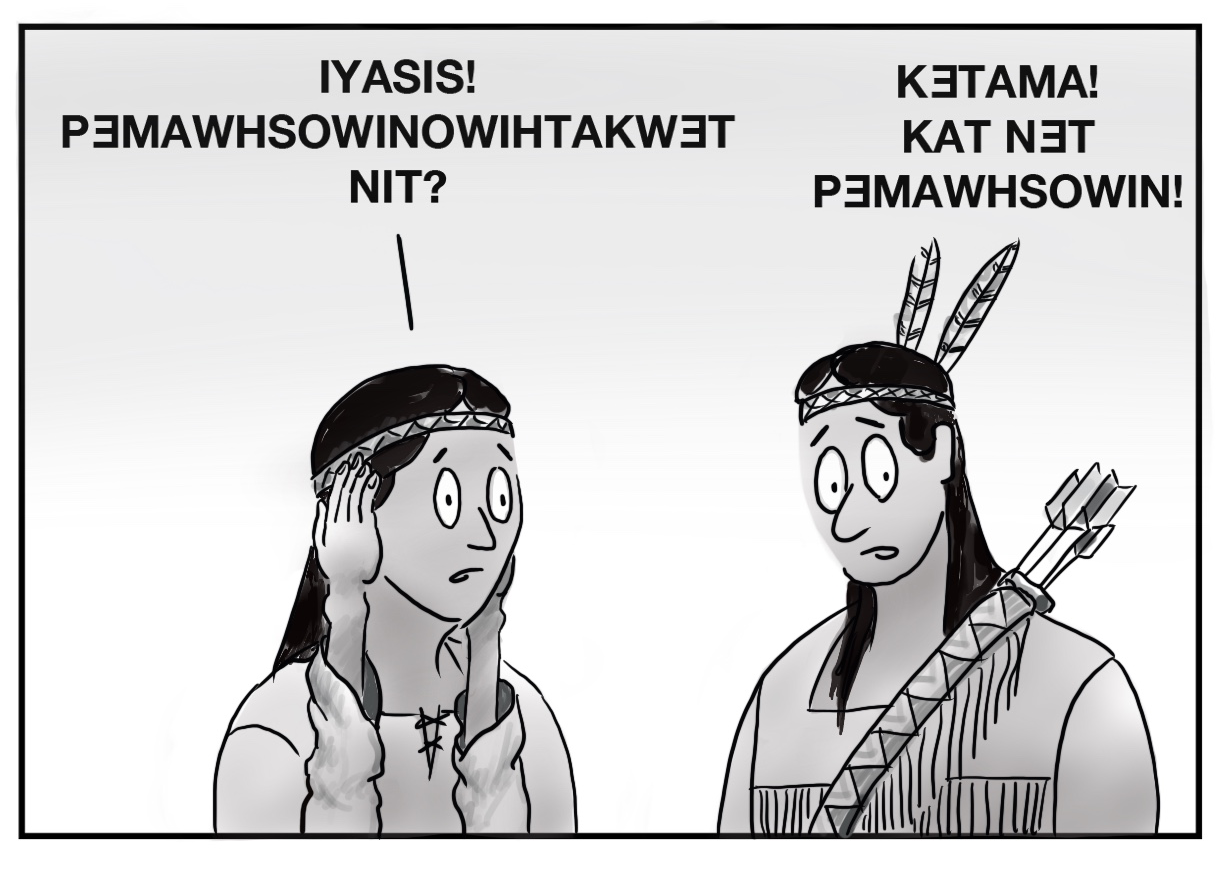

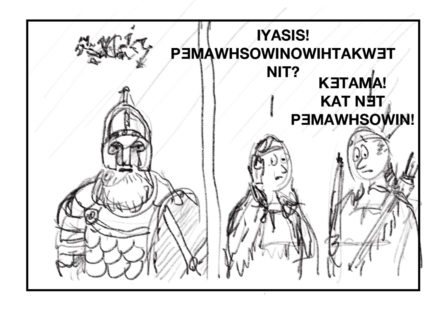

Translating the third frame made things a lot more complicated.

The Viking mutters his Norse greeting (which I do not know [my mother’s vocalization was very funny]). In response, the Wabanaki humans are aghast.

WHOA! WAS THAT NOISE HUMAN? IYASIS! PƎMAWHSOWINOWIHTAKWƎT NIT?

IYASIS! was an easy translation but PƎMAWHSOWINOWIHTAKWƎT NIT propelled me down my path of personal and semantic discovery again. My mother, without pause, provided the translation to evoke the query “is it making a human sound?” My initial impulse was to characterize the Norse utterance as ”noise” but my mother afforded the stranger the possibility of human attributes. At one point I asked, “What is the Maliseet word for noise?” When she told me, I recalled it as a familiar word describing unpleasant sounds. Yet, my mother insisted on allowing the stranger the benefit of the doubt. It was another lesson about perceptual stance on social relations through semantic nuance. I really should be going native!

The closing sentiment, “Nope. Not human.” was straightforward.

NOPE! KƎTAMA!

NOT HUMAN! KAT NƎT PƎMAWHSOWIN!

The translation prompted no hesitation from my mother and elicited no queries or quandaries from me.

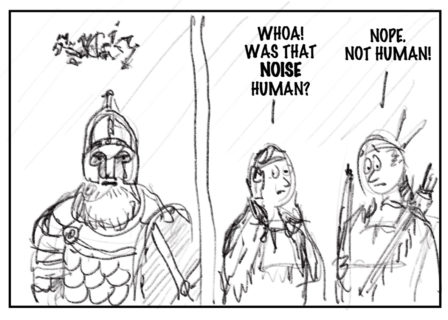

I now had to transfer the Maliseet text to the graphic outline.

Ooops! This is not going to work! It seems the grammatical structure of Maliseet and English are different enough to force me to change the composition and restructure the dialogue. English has a convenient isolating structure. The original version was so simple! The Maliseet version messed up my plans for composition and presentation of the punch line; I couldn’t simply drop the Maliseet translation into the English graphic composition. Back to the drawing board. I learned a huge lesson: I need to start in Maliseet and translate into English. In short, I need to go native.

When the Viking responds in his language the sounds are meaningless and unrecognizable. The only conclusion the Wabanaki humans can make is that the stranger is not human after all. This punch line emphasizes the harm that can be done to others when the presuppositions latent in our respective language ideologies reify our prejudices. I hope the cartoon provides a cautionary tale reminding us to try to see encounters from both sides.

It was important for me as the creator of the “Going Native” series to provide a cartoon in an indigenous language; namely, Maliseet. Presenting the cartoon in an indigenous North American language allows me to highlight the reality that many indigenous people face on a daily basis—we are continually confronted with alien languages. The cartoon also provides opportunity to address the historical linguistic imperialism that sought to demean, trivialize, and dehumanize the languages of the native peoples of the western hemisphere and other colonial contexts—and to have fun while doing so.

Christopher Columbus wrote in his journal on October 12, 1492, “They ought to make good slaves for they are quick of intelligence since I notice they are quick to repeat what is said to them, and I believe they could very easily become Christians, for it seemed to me that they had no religion of their own. God willing, when I come to leave I will bring six of them to Your Highnesses so that they may learn to speak.” This excerpt from Columbus’s journal may be the first expression of “old-world” linguistic imperialism imposed upon the first peoples of the so-called New World. William Shakespeare would echo such sentiments through the voice of Miranda in The Tempest,

I pitied thee,

Took pains to make thee speak, taught thee each hour

One thing or other. When thou didst not, savage,

Know thine own meaning, but would gabble like

A thing most brutish, I endowed thy purposes

With words that made them known.

We know what Columbus and Shakespeare thought about the native peoples of the Americas and their languages, and we’re witnessing the results of five centuries of linguistic imperialism in the current global linguistic crisis of language endangerment and extinction.

Today, we participate in reverse linguistic imperialism not as a silencing mechanism but as an opportunity to learn indigenous languages to understand indigenous worlds. The Maliseet translation of “Going Native” is SKICINOWI PƎMAWHSOWIN, which means “living like a native person.” Welcome everyone to native North America.

I want to acknowledge the lessons in language, life, and generosity from my mother who provided the Maliseet translation and lessons in personal discovery. I also want to acknowledge the unwavering support of Natalie Konopinski and the great staff of the AAA publications team for their valuable work to make this celebration of IYIL possible.

Bernard C. Perley is Maliseet from Tobique First Nation in New Brunswick, Canada. He teaches courses in linguistic anthropology and Native American studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He combines his art and architecture background with ethnography to promote indigenous language revitalization and social justice issues. And, he loves drawing cartoons.

Cite as: Perley, Bernard. 2019. “Going Native…In Other Words.” Anthropology News website, September 19, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1262