Article begins

Homebirths are often imagined as either an outdated practice of low-income countries or an emerging New Age spiritual practice. Yet tracing the homebirths of women in Istanbul tells us a different story. With the neoliberalization of health care and widespread obstetric violence at hospitals, homebirths are more popular than ever, connected with a broader, transnational movement of alternative medicine. And with COVID-19 continuing to strain hospitals, the phenomenon seems unlikely to wane.

Despite popular belief, homebirths occupy a gray area between legality and illegality in the Turkish system of law. This legal position dates back to the Ottoman modernization reforms, which banned “traditional” midwives from attending childbirths and fined the educated ones for malpractice. While there is currently no effective law that bans homebirthing, the practice has generated controversy and faced criminalization. There is a penal fee for midwives who work at public hospitals and attend homebirths. Independent midwives who work at their own health clinics (called sağlık kabini in Turkish) could risk their permits if they attend homebirths outside of the city where their clinics are located, and it is illegal for medical doctors to attend homebirths. Then why do people demand homebirths and midwives offer them, undeterred by legal complexities? For expecting families, given the soaring costs of private care and how public health institutions’ approach to childbirth resembles an assembly line, homebirth has emerged as a viable alternative. On the other side of the equation, when the exhausted, overworked, and underpaid health workers were hit by the pandemic, the risks of legal action seemed reasonable compared to bigger risks of violence and harassment they faced every day at hospitals. The growing popularity of homebirths underscores how, amidst compounding crises, homebirthing offers an alternative model of care for midwives and birthing people.

On January 13, 2022, a pregnant woman in Ankara attempted a homebirth. Hours later, the baby showed up in a breech position and became stuck in the birth canal. After an ambulance took the birthing woman to the hospital, the baby was pronounced dead. The final medical report specifies the reason for seeking hospital care as a homebirth attended by a doula. I later learned that the parents tried unassisted childbirth at home, and when they realized something was wrong, they called a friend for help, who then took them to the hospital. The hospital staff who wrote the report assumed the nonmedically trained person who came with them was a birth coach. This case has now gone to court, but leaves us with the question, Why would an expecting couple with universal health care access and in an urban setting, attempt a homebirth?

As a part of 26 months of fieldwork on the politics of childbirth in Turkey, I interviewed nine homebirth midwives, 23 homebirthing women, and three women who planned their homebirth but eventually ended up at the hospital. These homebirth midwives are currently in the process of creating an independent midwives’ advocacy group as they are not represented in existing midwifery organizations, which prefer to avoid legal implications regarding homebirth. When I saw the news about the couple in Ankara, I called Arzu (a pseudonym), a popular homebirth midwife I met during my fieldwork, praying that she was not the doula reported in the news. Luckily for her, she was not. She stopped attending homebirths until media attention tapered off and it was safe to do so again—legally and practically.

In the United States, the controversy regarding homebirths arises from the rift between direct entry midwives (DEM) and certified nurse midwives (CNM). In Turkey, all midwives I interviewed were educated in mainstream schools with a biomedicalized understanding of birth, thus homebirth midwifery indicates a shift in their practice. Arzu is a daughter of a midwife, both she and her mom were educated in midwifery schools that were first opened in 1841 by Besim Ömer Pasha as a part of biomedicalization efforts during the Ottoman modernization. She started practicing midwifery in 1988 and has attended more than 12,000 births even though she is only 55 years old this year. When I asked Arzu what made her turn to homebirths, she recounted one event that was the final straw among many incidents of obstetric violence.

At the time, she was working at Konya Birth House, one of the most crowded clinics in a city known for its Islamist conservatism. In that clinic, midwives were taking care of the laboring women until the actual moment of delivery, since childbirth is an event that can take up to 72 hours. The doctor on call had a nasty temper and was usually tense with the midwives.

One night, the clinic was unusually busy, thus the attending doctor was extremely irritable. Arzu and other midwives did their best to support a laboring woman until it was time to call the doctor to crown and deliver the baby. Finally, the doctor arrived. Arzu was trying to hold the woman who was about to give birth. She touched her belly and immediately realized that something was wrong. Trying hard not to transgress her assigned inferior place as a midwife, she warned the doctor in a panic. Her pleas were met with a slap across the face. Arzu was six months pregnant at the time. Her midwife colleagues in the room told her to leave. She received the bad news during her next morning shift: the woman whose delivery she attended died shortly after from a hemorrhage due to a rupture, as she had correctly guessed. Distraught, she was called to the doctor’s office.

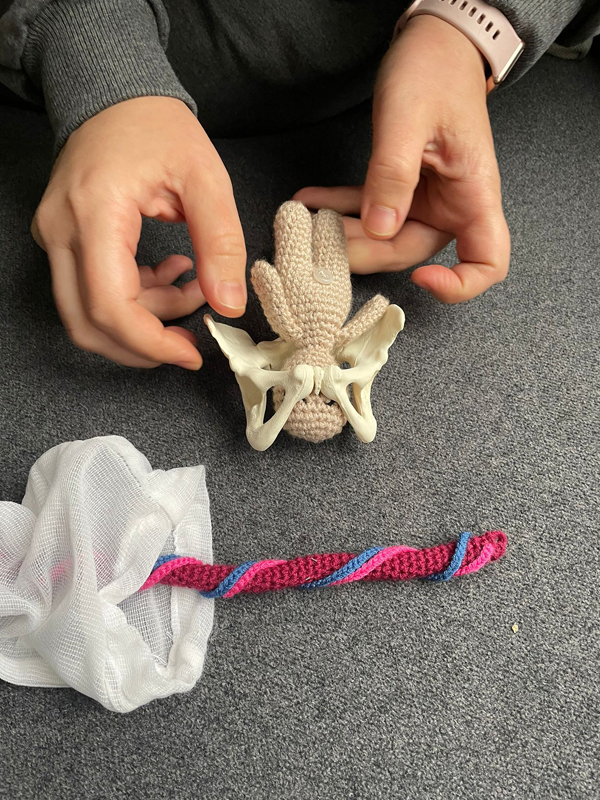

To Arzu’s surprise, she didn’t find the doctor aggravated or angry. It was his apathy that convinced her to leave. The doctor told her that the late woman’s family had brought him chocolate for his care and efforts and asked Arzu if she wanted some. Her job was hard, the pay was low, but she reiterated many times how much she loves being a midwife. Around that time, a friend mentioned the Istanbul Academy of Childbirth, an institution that offers classes to become a doula. She had her retirement savings and was eager to learn and improve her knowledge. The course she has taken at the Academy questions most of the standard practice in public hospitals. Instead of a forced C-section at the 40th week, they recommended waiting for childbirth to start spontaneously on its own until the 42nd week of pregnancy. Instead of immediate well-being tests on the baby, they prioritized mother-child bonding with skin-to-skin contact.

“So this is how you learned about natural childbirth the first time, when you were becoming a doula?” I asked her to confirm. Startled, she corrected me:

Of course, this is not the first time. As a matter of fact, almost nothing I learned was new. I saw my mom many times doing these things. In homebirths I attended when I was a student, we always placed the baby to mothers chest so they could see each other. And when a baby passed her due date, I never intervened except to tell the pregnant women to sweep the floors on all fours, it usually starts the labor anyway. But I wasn’t allowed to do any of these at the hospital under supervision of doctors.

The internationally accredited courses are not the only source for Arzu to find new (old) ways, to revise her knowledge and to keep up with the latest developments in the natural childbirth community. As she attended many foreign nationals’ (mostly Russian women) homebirths, she read the latest academic papers with the help of Google Translate. Through informal meetings with many midwives over the years she has managed to create another standard practice. She trusts her gut feeling above anything else. A midwife, she explained to me, feels what to do anyway. And she knew what to do when she was working at hospitals. She was just not allowed to act.

Arzu’s story is neither unique nor old. In the absence of a legal clause defining midwifery work and drawing its limits, thousands of midwives today are working in the first step health institutions, doing desk jobs and being at the forefront of raising violence against the healthcare workers.

As Faye D. Ginsburg and Rayna Rapp argue, reproduction is an entry point into the analysis of social life. The stories of conversion from mainstream midwifery to homebirths, even though they are limited in their numbers, underlines the structural problems that alienate midwives and birthing people. The pandemic has only exacerbated the problems with working conditions: the number of doctors leaving the country is at an all-time high, midwives are protesting against a pay rise for doctors as they are tired of being seen as second-class medical professionals, and physical violence against health workers is on the increase. As hospitals become riskier places in terms of health and safety during a time of pandemic, the home emerges as a sheltered space for work. However, in the absence of a legal clause that protects them, homebirth midwives are taking personal risks to offer their services and explore new possibilities of reproductive care based on experience, expertise, and intuition without the constraints of a broken system.