Article begins

Early in our fieldwork in Madrid, we were invited by the director of one of the youth-serving NGOs in our study to accompany her to a two-day conference, “The challenge of big cities in the context of crisis: Present and future of the children of immigration.” The conference, sponsored by the Madrid municipal government’s Department of Public Safety and attended primarily by police and social educators who worked with immigrants, aimed to provide information on the children of immigrants that would facilitate the goals of “social cohesion” and “safety” in Madrid. We sat in a packed auditorium as invited speakers presented various perspectives on immigrant conflict and revolt and ways to avoid it, spotlighting immigrant youth as potentially violent and dangerous. While it might seem curious that educators and the police would share the audience at a conference on immigrant youth, these groups represent twin arms of the state’s immigrant integration apparatus: law enforcement and education for integration. While law enforcement, including immigration authorities and the police, worked to surveil and contain immigrant youth as potential threats to public security, youth-serving NGOs like the two in our study, targeted immigrant students’ families and cultures for intervention and remediation to transform them into acceptable subjects of the liberal nation-state. In the citizenship education curriculum for one youth-serving NGO, for example, students’ “culture” appeared several times as a “risk factor.”

In our research with Latinx and Caribbean-origin youth in Madrid, in two after-school programs in youth-serving NGOs, we found that they were deeply affected by dominant nationalist discourses that constructed them as objects of fear—potential security threats—or as objects of hope who were leaving their parents’ cultures behind to take on European ways (as in the discourse of “positive integration” we found among educators and social workers). At the same time, their lived experiences in transnational social fields and the forms of cultural hybridity and diasporic citizenship they enacted were mostly invisible to the agents of the state responsible for “integrating” them: teachers, social workers, after-school educators, the police. Seen only through the lens of extremism or criminality, transnational experiences are the very realities that national integration regimes aim to curtail, as exemplified by recent laws in Denmark to criminalize extended homeland trips. So it should come as no surprise that studying them is difficult, that young people might not be immediately forthcoming about these realities to an unknown outsider. When seeking to understand young people’s transnational lives, therefore, we have to work especially hard not to think like a state.

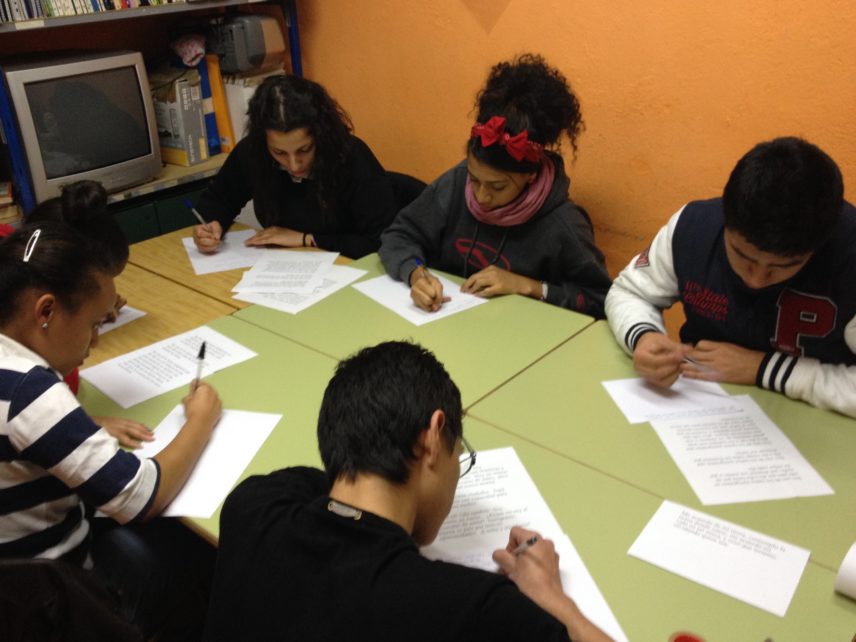

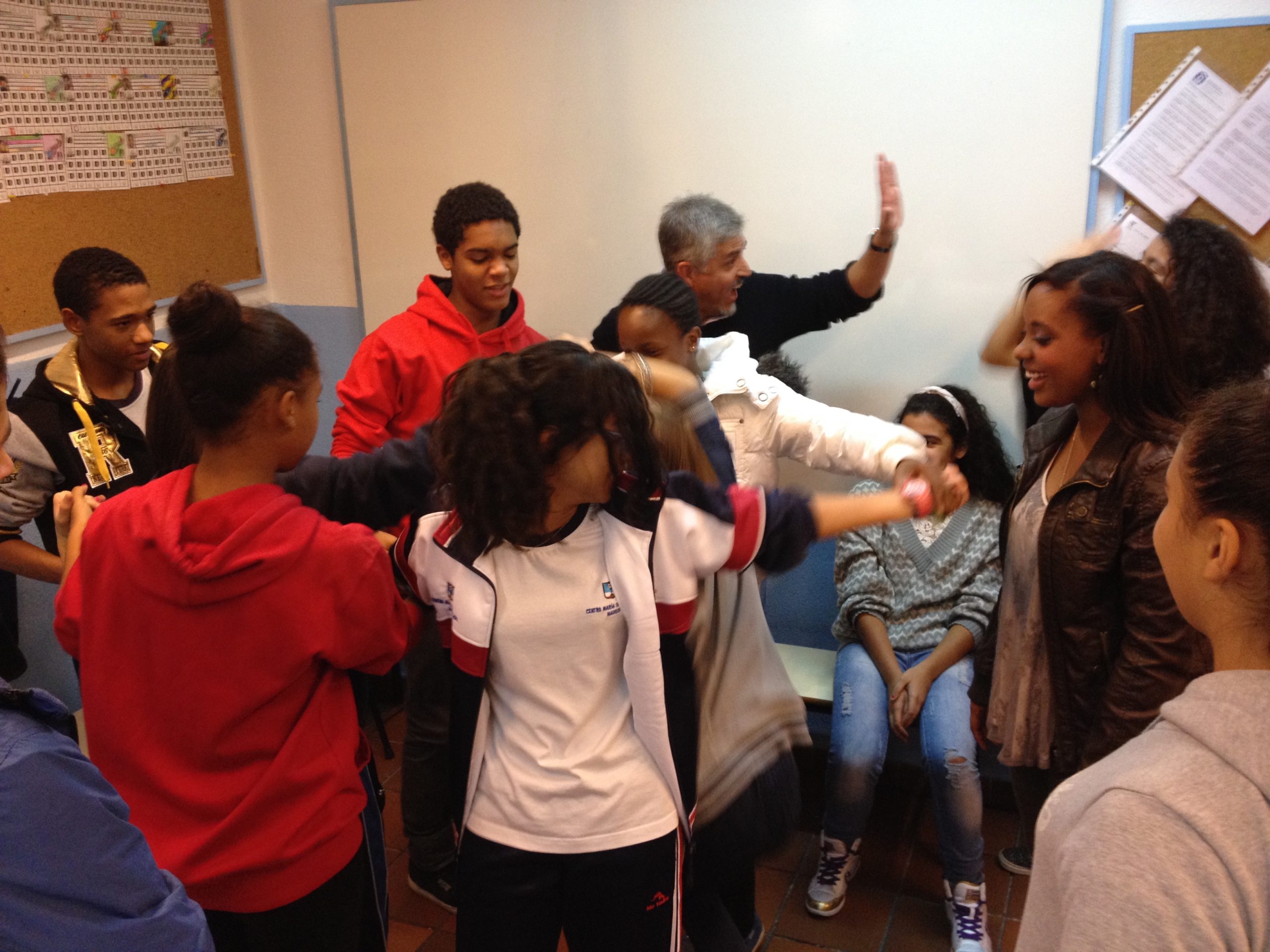

The above example from Madrid is one of several sites where we examined how young people growing up in the Latinx diaspora contend with dominant regimes of citizenship, even as they create and imagine new forms of identity and belonging that transcend national borders. Working in Northern California, El Salvador, and Madrid, we consider how epistemologies, methodologies, and pedagogies of the borderlands invite new ways of narrating and making visible lives in between, at the margins and interstices of multiple national communities. We found that conventional ethnography is not enough to get beyond the nationalist and “imperial detritus” (Abu El-Haj 2019) that weighs on migrants’ lives and to unearth hidden insights of transnational lives. While critical ethnography in multiple contexts was essential to trace the larger public and policy discourses surrounding immigrant youth, we also needed multiple methods of engaging young people’s lived experience, including poetry, dramatic role-play, video, identity diagrams, and participatory modes of inquiry, dialogue, and reflection. This is because observing everyday behavior and conducting formal interviews within spaces controlled by the state, whether schools or state-funded after-school programs, can only capture performances designed for the state: young people’s performance for national actors and institutions. Performances can tell us a lot about how young people embody, negotiate, and sometimes resist nationalist discourses of belonging, but they can’t tell us what they contrive to keep from view, or in the words of Gloria Anzaldúa, what “missing and absent pieces” must be “summoned back” to make them whole. This kind of work takes place in the space she called “Nepantla”: “the point of contact y el lugar between worlds—between imagination and physical existence, between ordinary and nonordinary (spirit) realities…where wholeness is just out of reach but seems attainable.” Likewise, a single disciplinary tradition cannot illuminate this work in-between, so we draw from interdisciplinary conceptual frameworks of borderlands feminisms, Chicanx/Latinx Studies and decoloniality.

In the space of Nepantla, 16-year-old Gabriel struggled to remember an older brother in Ecuador whom he had not seen in many years, and narrated his sadness at being separated from his native land. Although he was able to talk to his sister and his grandfather there occasionally through Skype, his brother lacked Internet access. On hearing this, his fellow student Paula, from the Dominican Republic, suggested that Gabriel talk to his mother about his brother, and look at photos of the family. In dialogue groups like this one, which we convened in all of our multiple study sites, diaspora youth accompanied each other in their efforts to “summon back” the missing parts of themselves. Across our locations, we consider how our own subjectivities as transnational US Latinx scholars nurtured our capacity to recognize, support, and create spaces of acompañamiento and autoformación (self-education), borderlands pedagogies that center migrant youth as experts and co-researchers of their own experience in the mutual effort to recover fragmented lives. Youth read and reflected on poetry written by other migrants, then wrote and discussed their own; they interviewed members of their families and communities about the experience of migration and discussed their findings with a public audience; and we engaged in deep and sustained dialogue.

For 14-year-old Raquel, who had moved to Spain from the Dominican Republic when she was 6 years old to be reunited with her mother, it was poetry written by undocumented Mexican migrant youth in California that got her to start talking. She said she identified with one of the poems because she also had to leave her country behind, and she still wasn’t sure it was worth it. While she migrated to be reunited with her mother, the move separated her from her extended family, replacing one loss with another. She talked to her grandmother and other family in the Dominican Republic regularly on the Internet, but “it’s not the same thing to be talking through Facebook or Skype as to be there, giving them a hug.” When Raquel presented with us on our research to an audience at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, she used the occasion to disrupt narratives of the “Spanish Dream,” telling the audience that since she had arrived in Spain, “I have not spent a single full day with my mother.” Her mother had sent for her and her brothers to be together, but “worked without rest from Monday to Sunday, like the circular [metro that circles the center of Madrid].”

Dialogue groups that centered the lived experiences of diaspora youth provided an opening for students to retell experiences that defied dominant discourses of integration: including experiences of racism and racialized police violence in Madrid that made it impossible for them to “belong,” and experiences of communal life in their home countries, where neighbors “help each other out and everyone knows each other,” and intergenerational parties with music and dancing where “alcohol is not essential.” Most importantly, national integration lenses could never capture the stunning complexity of their lives, marked by back and forth movement between countries and family members, languages, and cultures. As 15-year-old Rolando, born in Madrid to an Ecuadorian mother and Dominican father and raised in rural Ecuador and Madrid, explained, “When I’m there [in Ecuador] I want to stay, but when I’m here I don’t want to leave…I don’t choose either side: not Spanish, not Ecuadorian, nor anything.” The youth made it clear that they could not be complete in any one of the places of their experience, and their identity formation was an ongoing, incomplete process, fraught with loss and longing.

Across all locations, when invited to reflect on lives and loved ones “over there,” young people become self-aware of the limitations of national identity and, especially, the fallacies and contradictions of Western supremacy that promise superior lives in countries of immigration (whether Spain or the United States) while buttressing violent regimes of inequality. Their critique emerged organically through the comparison of life in two places, but for most of the youth, never translated into activism. In one of our study sites, however, young Latina activists at a feminist activist association in Madrid consciously recalled experiences from Latin America to critique citizenship politics in Spain and especially Spain’s treatment of immigrants. For them, refusing national identity was a conscious political stance, necessary to maintain their location in a “bridging house of difference,” as Chela Sandoval called the “third space” of Third World feminism. The activists made clear what was only a latent possibility for diaspora youth still enrolled in (state-led) compulsory schooling: that lives in transnational fields provide cultural resources for transcending inequality that are not found within the boundaries of a single nation-state. As Ruth Trinidad Galván reflected, recalling Anzaldúa, “For those of us born and raised transborderly, we are a countryless people, and more and more this does not sadden me.”

This column is based on Dyrness and Sepúlveda’s book, Border Thinking: Latinx Youth Decolonizing Citizenship (University of Minnesota Press, 2020), winner of the 2020 Council on Anthropology and Education Outstanding Book Award. Find out more about this annual award and the nomination process on the CAE website.