Article begins

Growing up my (Danielle) dad and I would read the newspaper every Sunday morning. He read the politics section and I read the comics. Those Sunday paper comics were my introduction to social commentary, and I was hooked from the moment I learned to read.

Supporting Indigenous students through their higher education journey requires a commitment from the institution, from offering financial assistance to creating infrastructure for academic success and retention. Yet, what often gets missed with these initiatives is an understanding of how to support Indigenous students’ social and emotional needs in a culturally relevant manner. As an undergraduate, I struggled to find culturally relevant support that normalized my experiences of being the only Indigenous student in the class, studying in a department with no Indigenous faculty, and suffering from severe homesickness. These experiences were extremely isolating and often left me feeling the full effects of imposter syndrome. It was not until my junior year that I realized these emotions and social experiences were the norm for Indigenous students pursuing higher education!

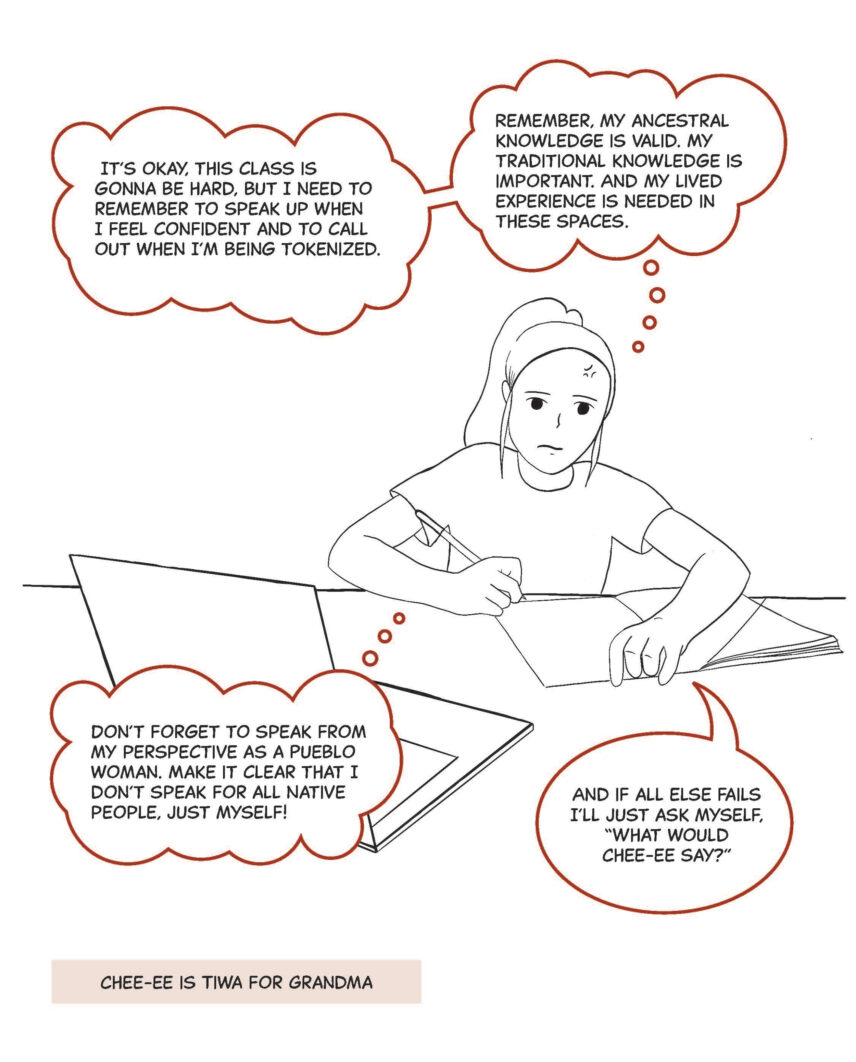

I started to draw comics based on these interactions, from experiences of being the “only” in a class to having to field questions like, “Do you live in a tipi?” Drawing comics helps to process the microaggressions and brainstorm retorts to ignorant comments. They also provide an outlet to normalize both my feelings of isolation and my ability to rely on family, friends, and traditional teachings to push through the hard days and celebrate the triumphant ones. Comics became a way for me to create culturally relevant support on the social and emotional journey that comes with pursuing any degree.

Turning Points: A Guide to Native Student Success, is a magazine made by and for Native college students. Produced at Arizona State University’s Center for Indian Education, Turning Points develops culturally relevant and timely stories, resources, and support for Indigenous students. Here, we (Danielle, the cartoonist and Taylor, the magazine’s chief editor) collaborate with other magazine staff on story ideas for each semester.

For us, the magazine and the comic strips we develop tap into a cultural understanding for many Indigenous students. In Indigenous communities, humor is a tool for healing and emotional support. We are peoples who love to laugh, through our heartache, through our successes; we are joyous people even in dark times. The comic strip allows readers to laugh but also shows that we are not alone in many of our struggles. They make room for Indigenous students to say, “That happened to me too!” or even inspire Indigenous students to challenge themselves or remind them that they are powerful and belong in these spaces.

Here is what you need to create culturally relevant comic strips to support and uplift Indigenous students.

A good team. An Indigenous person (preferably someone who likes to draw), a pen and some paper (or in my case, an iPad and an Apple Pencil), a sense of humor, and a magazine editor who is down to support you every step of the way.

Indigenous students. Check if your institution has Indigenous students enrolled. If they don’t… that’s a whole other conversation you should have with your university.

Conversations and connections. If there are Indigenous students, invite them to lunch. Share a meal with a Native and we will talk your ear off. After this meal, think about the experiences shared, think about your own experiences. What do you wish someone had told you in your freshman year, your senior year, or mid-graduate program?

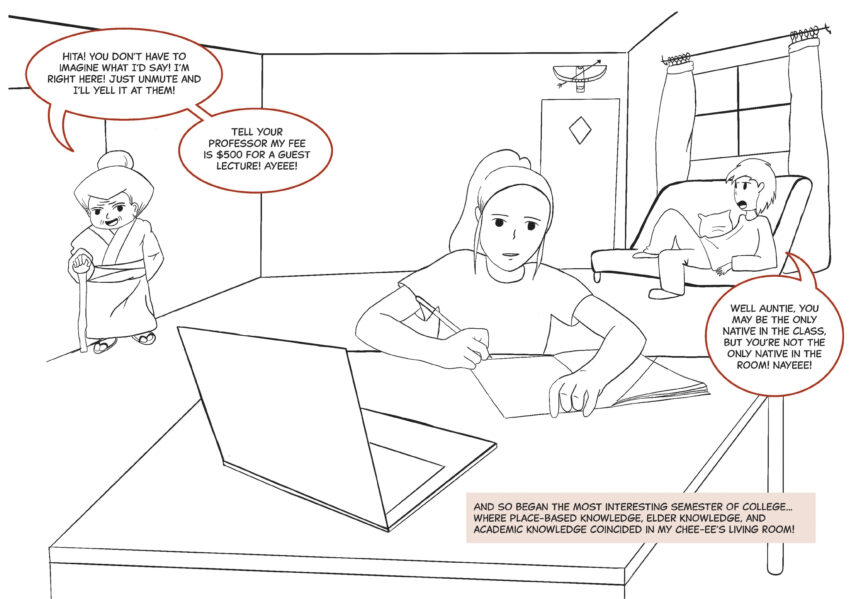

Start drawing. Pull from your lived experiences. Call your grandma and ask, “Hey Grandma, what advice do you have for when I really miss home and want to drop out of school?” Then figure out how to draw what she says. In my case, I drew a little old woman yelling, “Nooo grandchild! I want a free trip to New York City! Imagine me! In the city that never sleeps! Ayyeee!”

Be honest about the advice. Sometimes it’s hard to hear; sometimes it makes no sense until much later; and sometimes it’s not helpful at all, but it makes you laugh. Share that joy, that’s the point of culturally relevant comics: they are honest, authentic, and vulnerable.

Be vulnerable. Sometimes the comics provide humor and relief, and sometimes they provide a sense of shared experiences, both positive and negative. But sharing the failures, negative feelings, and experiences help normalize the process and journey that Indigenous students go through in higher education.

Drawing comics is easy and everyone can do it (I would never call myself a good cartoonist). But drawing comics for an audience that I deeply love and care for and sharing advice and vulnerabilities is hard work. It is not easy, but it provides a sense of pride and humility when I walk into my grandpa’s house and see cutouts of my comics posted on his fridge for my little nieces to read. Comics are how I learned to read with my dad on Sunday mornings, and now I draw comics for my nieces to read and imagine themselves in spaces they may not have ever thought possible.

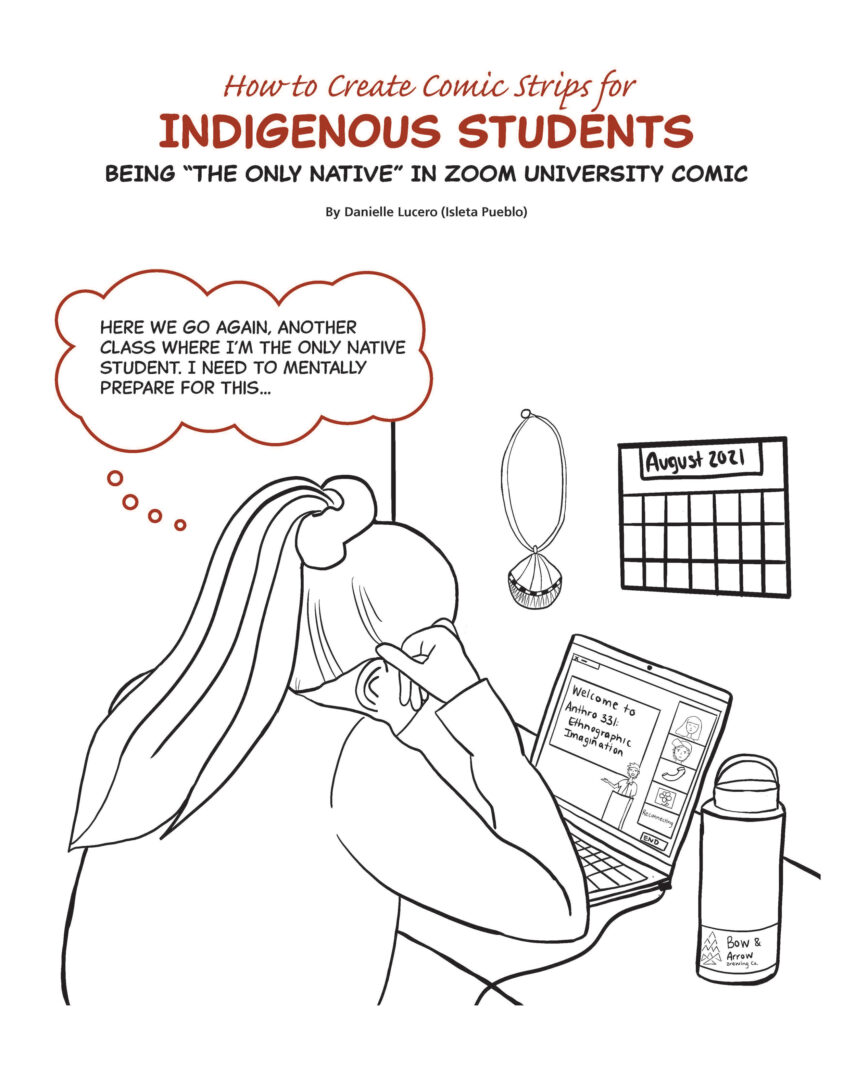

Below that, there is a person sitting at a desk, laptop open in front of them with a Zoom class meeting for “Anthro 331: Ethnographic Imagination” on its screen. She rests her head on her fist and stares at the screen, thinking “Here we go again, another class where I’m the only Native student. I need to mentally prepare for this…” On the wall is a calendar labeled August 2021 and a decoration hanging on the wall; beside the laptop is a bottle.