Article begins

Learning to play Javanese gamelan music in Indonesia and the United States is one of my greatest joys, challenges, and privileges as an ethnomusicologist. Gamelan are ensembles largely, although not entirely, comprised of gongs and keyed percussion instruments. The playing techniques of many of the instruments are accessible to beginners, including people without prior musical experience. (Some instruments are extremely difficult.) So how can one start to play?

Find a group. As an ensemble music, practicing with a group is necessary. While I have spent many hours practicing on my own, it takes playing with others to really understand how the part I am playing fits in with the whole, how to adjust with the shifts in the music, and how to interact with my fellow musicians. If you don’t know of a gamelan group in your community, I suggest an Internet search! The group will likely have access to a set of instruments.

Approach the instruments with respect. Gamelan ensembles are highly respected in Java for multiple reasons, including beliefs some hold about spirits and spiritual power in the instruments, the beauty of the instruments, associations with traditional culture, and in some cases, associations with prestigious courtly culture. For me, studying gamelan music has been a wonderful way to learn aspects of Javanese etiquette, such as taking one’s shoes off, not stepping over the instruments, moving slowly and carefully bent over to humbly lower one’s height, sitting on the floor, etc.

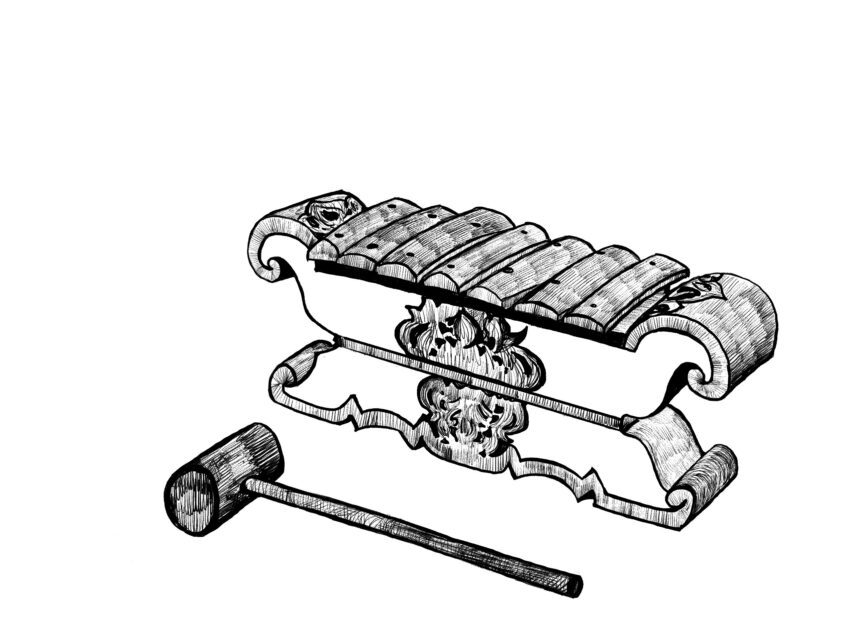

Start with an instrument that is relatively easy to play. I suggest the saron, a metal-keyed instrument played with one mallet. One advantage the saron offers to beginners is that the melody it plays is often played by other instruments, including other saron, so a beginner can follow or be reassured by another player. I recall fondly that the musician I followed when I was first learning to play as a college student on a study abroad program in Java was a young boy.

Learn to strike and damp the saron keys. The saron mallet is held in the right hand while the left hand is used to damp. First hit one key with the mallet, then while hitting another key, damp the previous key by holding it between your left thumb and index finger (thumb on top of the key, index finger beneath). Given the resonance of the keys, the melodic lines could become blurred without damping—although this could be done intentionally in more experimental music. Learning to damp may take some practice, but with time it usually becomes automatic.

As you practice striking and damping, take note of which keys are which pitches. Usually, saron have seven keys. In what is called the pélog tuning system, the keys are numbered (from lowest to highest) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. In the sléndro tuning system, the keys are often (although not always) numbered low 6, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, high 1.

Play a composition. Depending on the group, you may learn to play a composition with or without the aid of musical notation. If musical notation is used, typically numbers represent pitches and periods or dashes represent rests. For example, if the notation reads 3212, play pitch 3, then 2, then 1, then 2, damping appropriately. Each pitch is one beat. If the notation reads .3.2, rest for a beat, play 3, rest for a beat, then play 2, also damping appropriately. Additional symbols are also used, but this provides a basic introduction. If musical notation is not used, follow the direction of the teacher or leader, who may sing or play the melody bit by bit and have you play it back. If there are others playing your same part, you can also follow them. Gradually you will learn how your melody fits within the ensemble, enriching and producing the whole—and if you are open to it, you may experience a bit of magic as you create something powerful with fellow humans.

Illustrator bio: Letizia Bonanno is a social anthropologist and comic artist based in the United Kingdom. She has worked and researched between Italy and Greece, looking at the emergence of social medicine in Italy and grassroots medical facilities in Athens. Since 2014, she has produced illustrations and short comics about the social clinics of solidarity and the economic crisis in Greece; she has also written on the affordances of the graphic medium for teaching, research, and public engagement.