Article begins

Smack dab in the middle of a virulent pandemic, we (a group of four faculty members from diverse disciplines) were handed the challenge of helping students process what they were experiencing from both academic and direct action perspectives. Moreover, we were tasked with doing so from some very different perspectives and preparing students to work with growing global complex problems based on the example of the pandemic. COVID-19 affected many parts of the institution, so we needed to satisfy the intellectual and sometimes emotional needs of students from a fairly wide variety of disciplines, including international development, translation and interpretation, nonproliferation and terrorism, environmental policy, language education, and more. The course, COVID-19: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on the Pandemic, aimed to emphasize intercultural competence—fostering students’ ability to effectively listen to, communicate with, and take action in communities with a range of linguistic and cultural backgrounds. The four instructors are trained in applied linguistic anthropology and intercultural communication, organizational development and public administration, economics and finance, and public policy analytics. It was a unique opportunity for students to conceptualize the pandemic in interdisciplinary ways and prepare themselves to employ these lenses in future complex situations.

| One practical inference that I am drawing from this week, is that interdisciplinary opportunities always exist. Regardless of business type, office type, location, or time, they exist. Considering how we can form bridges into other worlds for our clients, students, or businesses is crucial. How can we set up partnerships that make it easier for our clients to solve their complex problems? How can we educate our organizations about the interrelatedness of our work and other’s work? —Abigail Gray, MA student in international education management and program administration. Canvas discussion post, November 19, 2020. |

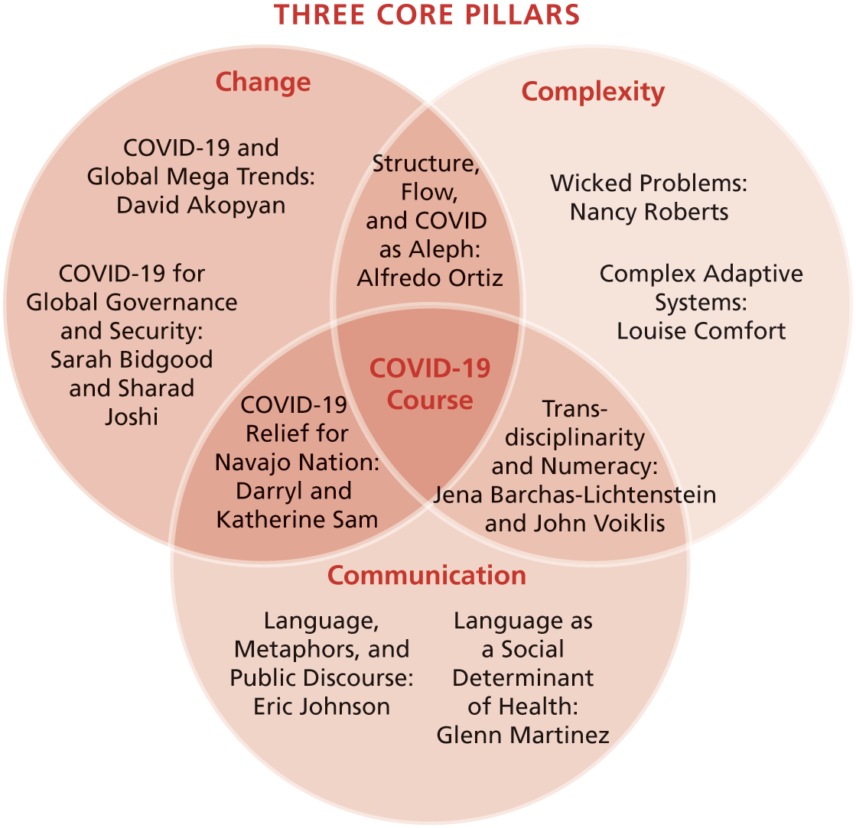

We designed the course around three core pillars—complexity, communication, and change. The complexity pillar focused on COVID-19 as an example of an extremely complex problem with multiple causes, consequences, nonlinear causal relationships, and different stakeholders with competing interests and distinct ideas of what the key problem even is. This lens enabled us to draw parallels to other extremely complex problems like climate change, and also apply analytical frameworks for addressing complex problems. The communication pillar highlighted the role of various forms of communicating across multiple stakeholders with diverse perspectives collaborating to deal with complex problems. The change pillar was action oriented; here we wanted students to leave the course with concrete tools for changing attitudes and behaviors in order to handle complex issues like the pandemic. Across the three pillars, we emphasized critical analysis, active engagement, and design thinking approaches, using multiple cases.

Given the challenge of teaching this course, throughout the semester the teaching team embodied Edwin Hutchins’s notion of “distributed cognition,” the idea that impactful knowledge is shared across individuals. We accomplished this by humbly recognizing the limits of our own expertise alongside the interdependence of our knowledge bases as we collectively moved toward meaningful action. We encouraged students to reframe complex global problems and navigate them as situations evolve. Our initial challenge was in providing a rich set of perspectives in a manner that allowed successive positions to reflect, draw upon, or otherwise complement earlier views. To that end, we hosted 16 guest lecturers from different sectors, including community organizations, health services, international security, and critical discourse analysis, alongside framing discussions, reflections, and small group discussions facilitated by the course faculty. For example, David Akopyan, a senior advisor on crisis, fragility, and complexity discussed global megatrends exacerbated by the pandemic (change). Glenn Martinez, director of the Center for Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at The Ohio State University, shared about his collaborative research and advocacy about language access for Spanish speakers in community health care settings (communication). Darryl Sam and Katherine Sam spoke about their on-the-ground engagement advocating for COVID-19 relief with the Navajo Nation (change and communication). Louise K. Comfort, an expert in decision-making in crises and the use of technology to inform managers operating under urgent conditions, discussed approaches to complex adaptive systems (complexity).

To make these complex and interacting perspectives more natural to process, we employed a foundation that progressed from macro to meso to micro levels of processing and understanding. That progression allowed us to begin with an exploration of the complexity embodied in wicked problem scenarios—complex problems with no clear solution—and then gradually move through concepts of social systems, communication, and individual processes that are inseparable from the overall system.

| STUDENT PROJECTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| What | So What | Now What | |

| Complexity |

|

|

|

| Change |

|

|

|

| Communication |

|

|

|

Student projects, integrating the course’s three pillars, used a What (in-depth description from multiple perspectives), So What (analysis, synthesis, interpretation), and Now What (implications, action) structure. By identifying critical elements and dimensions of systemic change processes, students learned to analyze and communicate patterns and frames, evaluate situations using multiple perspectives, and develop creative cross-disciplinary approaches for addressing complex problems.

The fact that everyone was experiencing the overall wicked problem of the COVID-19 pandemic made the course at once phenomenological and removed. We were all presented with the opportunity to analyze how individuals and groups were processing and interacting with the pandemic as we lived through it. The technosocial online format facilitated more complex, synchronous, and frequently asynchronous communication than we would normally be able to sustain in an in-person class environment. The course therefore allowed us to cultivate knowledge, skills, and dispositions relevant for both experiencing and analyzing a complex problem. Our own participant-observation efforts—in relation to one another, our disciplines, and our students—reveal how our interdisciplinary approach engaged with students as a model to begin solving complex problems. The course was not dominated by any one person or perspective, and the distributed cognitive space that developed was negotiated early in the course’s development.

| COVID is ever-evolving and this course taught me how to think about this change. But it also taught me to be more observant in the present, and focus more on tangible tasks I can tackle now. Like with any crisis, the opportunity to take on COVID will come knocking, and I want to make sure I am paying attention when it does. —Rose Thompson, MA student in international policy and development. Canvas discussion post, December 4, 2020 |

Interdisciplinary co-teaching experiences

Angela

As an international education management master’s candidate, I was drawn to the interdisciplinary aspect of this course and wanted to learn more about how people were addressing COVID-19. The pandemic is drastically exacerbating socioeconomic inequities. I believed taking this course would give me a better understanding of how to approach tackling these challenges. As the teaching assistant, I brought a professional educational background while the professors built the dynamic, innovative course. As an observer for both the students and the professors, and with a human-centered approach, I advocated to enhance the online learning and teaching experience. We created a community that showed us all what we are capable of doing when we use our strengths across disciplines to undertake wicked problems. The teacher–student experience was a reciprocal process, and holistic design in online learning was key to our success. Due to the nature of the course, it was easy to make connections across my other courses, from managing budgets to learning about environmental conflict. With its solutions-based approach to COVID-19, the curriculum taught me how to break down barriers across disciplines to create tangible solutions.

| There was a sense of collaboration, communication and critical thinking toward each subject through the course and this space really allowed for each individual to take part in the conversations we might not have been able to have with others. —Grizelda Ambriz, MA student in translation and localization management. Canvas discussion post, December 5, 2020. |

Fernando

I teach economic policy analysis, which entails a large amount of quantitative analytics. This means that most of the time my students and I are observing phenomena from afar, both in space and time, and certainly from an outsider’s perspective. This time was different. The global nature of the pandemic and the fact that we reside in a state hard-hit by COVID-19 in the United States made us participants in the process we were trying to observe and analyze. This is something with which I was not accustomed to dealing in my professional practice. It challenged my ability to adapt rapidly to new incoming facts and I became aware of how my perception of events impacted my analytical judgment. After some tribulations, I understood my role as helping students understand that we were balancing an insider/outsider dichotomy, accepting it as part of our practice. Denying or blocking our own perceptions would have prevented our students from taking full advantage of an opportunity that is rare in most of our fields of study. I am aware that this is common practice in some fields (social psychology, action-oriented research, anthropology) but it brought a level of reflection and novelty to our policy programs.

| The other insight that stuck with me on this project was the language and accessibility methods used to disseminate the information. For example, in one of the modules, I learned why it is problematic to use the wording war against COVID-19. —Daniel Zamora, MA student in program administration. Canvas discussion post, December 5, 2020. |

Maha

I have been teaching organizational management, leadership, and ethics in the Public Administration program. When the pandemic began, my colleagues and I saw an opportunity to bring a multidisciplinary approach to our teaching in the hopes of better preparing students for complexity while also stretching their minds. In designing and teaching this course we took our first step, and I already experienced challenges and promises of new ways of teaching. Creating and delivering this course was itself a complex problem that required us to suspend our assumptions (and with that, also check our egos tied to our disciplinary identities), be open to others’ perspectives, appreciate their unique strengths, and continually adapt to find the best path forward. As someone who is action oriented my contribution has been in steering the course toward “now what” kinds of questions and focusing on practical applications. In that spirit, I am now asking a new set of questions to build on this course and experience.

| These insights have allowed me to design my project complementary with existing work while taking what I have learned into account. In the course, there was a sense of collaboration and a consistent interdisciplinary approach toward each of our projects obtained through feedback and opening sharing of project ideas. Each week’s module focused on a different population and lens with the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing for holistic and comprehensive tools and deliverables. —Daniel Zamora, MA student in program administration, Canvas discussion post, December 5, 2020. |

Netta

I am an applied linguistic anthropologist; in collaboration with colleagues we analyze interaction, language, and discourse in connection with power, privilege, and inequity with a goal of social change. As the course came together, I had assumed that my main contributions would focus on communication; it was enriching to learn about new ways of conceptualizing language from interdisciplinary colleagues and guest speakers. The range of diverse voices in the course allowed us the opportunity to enact multivocality and “audience coalescence,” building bridges across multiple perspectives and challenging us to see what we are/are not experts on. We were all simultaneously in the roles of both speaker and user, listener and recipient, embodying anthropological principles of participant-observation. The course ethos is a microcosm of what we sought to teach the students—more heads are better than one and complex problems like COVID-19 can best be addressed through balancing structure with emergence. We realized the power of “CO-VID”: being together on video. A constant feeling of social distancing allowed us to strike a balance between experiencing COVID-19 as both familiar (part of our everyday experience) and strange (something we can only understand through learning others’ perspectives). It was an enriching process to feel ownership of the course while recognizing that the way it unfolded would be beyond my individual control—an interdisciplinary lesson that sticks with me in regard to the pandemic as well.

| Many times one simple/complicated/complex problem combines with another (or many) and results in a wicked problem. Since the start of this class, I have noticed myself making these types of connections and trying to figure out how to have a solutions-oriented approach and how we can use design thinking to find these solutions. This can be so discouraging when so many different forces are at play. I found it encouraging to hear the silver linings and positives that have come as a result of all these problems. This made me connect to the speakers we had last week… “Necessity is the mother of invention.” What new normals will we see as a result of all of these wicked problems? —Grace Davis, MA student in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL). Canvas discussion post, November 20, 2020. |

Phil

My early graduate work was developed in the area of cognitive social systems. Although currently my teaching focus is in analytics, I am fascinated with how cognitive systems ingest, process, and ultimately create the scenarios that surround them. It was a joy for me to be a part of a course that both analyzed these concepts and developed an emergent system of shared cognition. When we are in the middle of a large, wicked problem, it is easiest to focus on our immediate needs and environment. What is left over is chaos and confusion. Interpersonal networks that form social systems are generally closed, or semipermeable in nature. So, constructing a social system, as we do in every course to some extent, combined with the process of consciously examining what makes such systems function to develop a meta-understanding of the pandemic’s effect. That, in itself, was wicked.

Participant-observation pedagogy

Our interdisciplinary experiences of co-teaching this class demonstrate the importance of a participant-observation pedagogy for complex problems—one in which we are all teachers and learners at once. This approach honors each individual’s unique perspective alongside the group’s complementary strengths. In many ways this course was reactive to the circumstances of the pandemic and also proactive in its forward-looking focus on addressing future complex problems. This collaborative pedagogical model can be adapted for examining diverse wicked problems, fostering students’ and faculty members’ abilities to draw from their own experiences and analyze complex issues from a distance as we work together to find solutions.

This course has challenged us to reflect on how the goals and methods of graduate education can match the needs of an increasingly complex world. Working with multidimensional problems such as the climate crisis, poverty, women’s rights, and political polarization requires an emergent approach that builds on diverse perspectives of stakeholders and disciplines, continual communication and adaptability, experimentation and innovation, and commitment to sustain this engagement. Interdisciplinary approaches are imperative for addressing the global human problems of our time. Yet many graduate-level courses confine students to the limits of faculty members own disciplinary boundaries, partly because we slice up larger issues to examine them closely using a particular set of lenses (and may forget to put the pieces back together!). In many cases we may grow comfortable within fragmented but more manageable walls, reinforced by our different networks, conferences, and disciplinary language.

Cultivating new ways of perceiving and working with complexity requires long-term engagement with ideas and with one another. Synthesis of novel perspectives and ideas—what we hoped to instill through the course’s focus on COVID-19—necessitates time, commitment, iteration, and experimentation. We see the role of graduate education as a place where students come to sharpen their minds and critically review their pre-existing assumptions in light of new perspectives. How might we collectively innovate in our pedagogy to ensure impact and relevance in a complex world? How can our courses embrace interdisciplinarity and emergence in terms of content and process? In our experience, balancing participation, observation, and distributed cognition can help us to find answers to these essential questions.