Article begins

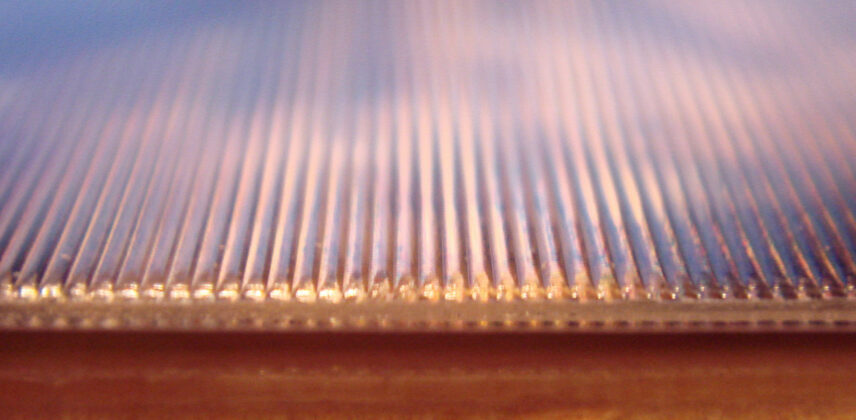

There is a mode of producing dual holographic images that give a viewer the impression of depth and movement called “lenticular printing.” To make lenticular images, you must first capture two images with a special lens and then print each on a sheet of plastic that has a series of lenses on the reverse. You then cut each image into thin strips and reassemble the slices in an alternating pattern. The result is something you may have seen on the cover of a friend’s notebook at school or on a movie poster in the nineties: a holographic image that, when viewed from one angle, shows a subject, maybe a superhero or animal, in a given pose and, from the opposite angle, depicts the subject in a different pose. Two discrete photographs arranged in a particular way are combined so that a viewer moving from one perspective to the other sees a single composition that conveys a given subject with depth and dynamism.

I start with lenticular printing as a way to think about the possibilities and limits of anthropological research in contexts of instability and uncertainty. What does an anthropological inquiry look like when it is suddenly and unexpectedly bifurcated by a period of enforced distance and isolation? And how can such an inquiry be stitched back together? I ask these questions as a PhD candidate who, at the start of 2020, was planning to enter the field in September for twelve months of ethnographic research among Palestinian refugees from Syria currently living in the Shatila Palestinian refugee camp in Beirut, Lebanon. The pandemic put that plan on hold indefinitely. But it also offered me the opportunity to explore questions, deploy methods, and collect archival data that I would not have had the time or inkling to pursue otherwise. However, these archival methods cannot replace in-person ethnographic research—my project still relies on the ability to take a step to the other side and capture the image that emerges from the ethnographic angle. As with lenticular printing, archival and ethnographic snapshots, while different from an uninterrupted year of ethnographic fieldwork, can be interlaced to create a single work that captures a subject in all its nuance and complexity.

Prior to the pandemic, I planned to explore urban displacement in the Middle East through the lives of Palestinian refugee workers from Syria currently living in Shatila. In addition to conventional methods like semi-structured interviews and participant observation with refugees, I proposed methods like mobile walking interviews and mapping exercises that could identify how the links between Shatila and surrounding Beirut shaped refugees’ efforts to accommodate to unfamiliar circumstances in the camp. As the pandemic forced the world online, it became clear that I would not be able to carry out this research as planned. I therefore set about figuring out how I could conduct productive research from a distance while awaiting a chance to travel again. Guided by my interlocutors’ life histories that span the Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus and Shatila in Beirut, I decided to add comparative and historical dimensions to my project. I have explored the histories of these two camps through a variety of digital collections, including newspaper archives, multimedia collections, and grey literature from UN bodies and relevant NGOs.

Some of the most compelling data I have gathered has come from collections established specifically to preserve Palestinian history and culture. Historically, Palestinians’ enforced geographical dispersion and ongoing struggle for liberation has made collecting and archiving a fraught endeavor. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and its member factions have all kept records but these, like the organizations themselves, are dispersed geographically. Events like Israel’s 1982 seizure of the PLO’s Research Center archives further fragmented these collections. Recently however, multiple museums dedicated to preserving Palestinian history and culture have opened in the United States and Palestine. These institutions have been collecting and exhibiting objects, documents, and narratives that tell the story of the last 100 years of Palestinian history. Most of these efforts pre-dated the COVID-19 pandemic by several years. With the pandemic suddenly precluding in-person fieldwork, I have found many of these resources incredibly generative in exploring the historical dimensions of my research on urban Palestinian refugee camps. Among the most useful and most evocative are a pair of photo archives. The first is the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East’s (UNRWA) Film and Photo Archive, which has since 2013 been digitizing photographs from across UNRWA’s history of aid provision to Palestinian refugees. The second is the digital archive of the Palestinian Museum in Birzeit, which holds photographs alongside other digitized objects like magazine articles and documents.

The historical photographs hosted in these collections have provided vital insight into the changing built environment of these camps at different times. This is especially true of the photographs of Shatila in the 1970s and 1980s collected by UNRWA and the Palestinian Museum. During this period, Israeli assaults and, later, sieges by Syrian-backed Lebanese militias during the War of the Camps led to repeated rounds of widespread destruction in Shatila. The UNRWA and Palestinian Museum digital archives contain dozens of high-quality photographs from this period, in black and white and color, that depict Shatila in various states of destruction and reconstruction. These photographs emphasize that urbanization in refugee camps is not a linear process beginning with tents and unidirectionally developing into a telos of urban slums. Rather, hard-earned stability and security can be erased nearly wholesale, necessitating the periodic return of tents and emergency aid. Additionally, the photographs give clues to the materials and strategies of construction refugees used as they attempted to build and rebuild their homes. For example, a photograph taken during a truce in the War of the Camps shows laundry drying on lines on the roofs of concrete block houses. The houses pictured all feature naked rebar protruding from the vertical columns at the buildings’ roofs, the telltale sign of the intention to build more floors above. Another photograph of the same camp, taken at the conclusion of the War of the Camps, once again shows near-total destruction. The vertical rebar that attested to the desire for more floors rests on piles of rubble. Part of a magazine spread, this later photograph is accompanied by text stating “we will rebuild this camp, even if we liberate Palestine tomorrow.” Such images provide valuable insight into the deep affective and material ties these refugees have developed to the camp spaces they inhabit in exile, even as they participate in a national struggle whose stated aim is to return them to Palestine.

Having spent several months exploring these collections, I have come to appreciate just how valuable archival methods and data can be. The histories of these camp spaces, their changing built environments and the fundamental differences between Yarmouk and Shatila shape my interlocutors’ contemporary experiences in Beirut. But there are limitations on what data archival methods can provide. Some of these limits arise from the nature of the space itself; the assumption that refugee camps are temporary and the uncertain, unstable positions of their inhabitants means that information on these camp’s histories is difficult to locate and access. Moreover, I hope to learn about how my interlocutors, in the present day, make use of Shatila’s affordances and overcome its limitations—which requires me to be in the camp and observe everyday life.

Here is where the lenticular image can serve as guide. I am not the first person to look to lenticular printing in the context of ethnographic study. However, I see the lenticular metaphor as useful for thinking about how to reconstitute an inquiry that is split by unexpected distance and uncertainty. In-person ethnographic research remains necessary both for my project and the broader field of anthropology, but it is unclear when it will again be safe or ethical to carry out ethnographic research. Such ethical questions are especially fraught in the already over-researched Palestinian camps of Lebanon, where refugees have been dying of COVID-19 at three times the rate of Lebanese citizens. Due to these concerns, researchers like me will likely only have the chance to capture a brief ethnographic snapshot rather than pursue continuous year-long fieldwork. A lenticular approach offers a way to produce a textured and detailed work despite these limitations—both for my project and for the field of anthropology during and beyond the pandemic. By stitching together my archival and ethnographic snapshots, taken from two angles, during two different periods, and showing two distinct but related images, I will be able to construct an inquiry that captures the complexity of these refugees’ daily lives as well as the deeper histories of the spaces they inhabit. Furthermore, the current pandemic, devastating in its own right, is also an indication of the increasing precarity and uncertainty that characterizes the twenty-first century world. For anthropology, this means, among other things, less certainty when it comes to funding and time for extended research and increased possibilities of research being interrupted. Perhaps then a lenticular approach, one that sees snapshots as the building blocks for inquiries with a different sort of depth and detail, could provide a way to pursue anthropological research in an unpredictable world.