Article begins

“I wouldn’t want anyone to get attached to a space. But if, for the sake of an example, there is going to be a space, then it needs to be a space where people feel safe, where they feel welcome, where they feel invited, and where those who are holding space know how to do that…I’m grateful to hold space that way for us.”

This is Maya speaking, a yoga instructor who teaches classes throughout the city of New York. Beginning with a statement of non-attachment to fixed space—a clear indication of her preference to speak in terms of relationality rather than spatiality—Maya described the conditions for what she believed to be an optimal healing space for Black people. It must be safe and welcoming, and further, it is one of her duties as a healer to hold it. Maya is an affiliated practitioner of the new up-and-coming Black-owned wellness café in Brooklyn where I have been conducting fieldwork. The café serves two purposes as defined by the two co-owners. Firstly, it is a gathering place (café) where they serve coffee alternatives, teas, and pastries, complete with a few tables, chairs, and cushioned benches where their customers can congregate. In this way, it resembles a standard Brooklyn café or coffee shop. Secondly, it is a place of practice (wellness). Beyond the café area, you will find a yoga studio, private session rooms on the lower level, and an outdoor multipurpose area where the café hosts workshops and other small events. These are the spaces in which the practitioners that the co-owners hire offer health and wellness services in the form of Reiki healing, sound therapy, meditation, yoga, and others. Since its opening in May 2018, the café is quickly becoming a place of significance for many people. Some of the regulars include a young birth worker, a businesswoman who comes in to work on slow days, a young couple, their toddler. And since my initial visit, the number of affiliated practitioners has grown by nearly fifty people—some of whom offer services regularly and others who have hosted special one-time sessions or workshops. More than a café, this is a gathering space where people are invited to tend to the needs of their individual, social, and political bodies, which are constantly intermingling, dissociating, and coming back together again.

Maya described the conditions for what she believed to be an optimal healing space for Black people. It must be safe and welcoming, and further, it is one of her duties as a healer to hold it.

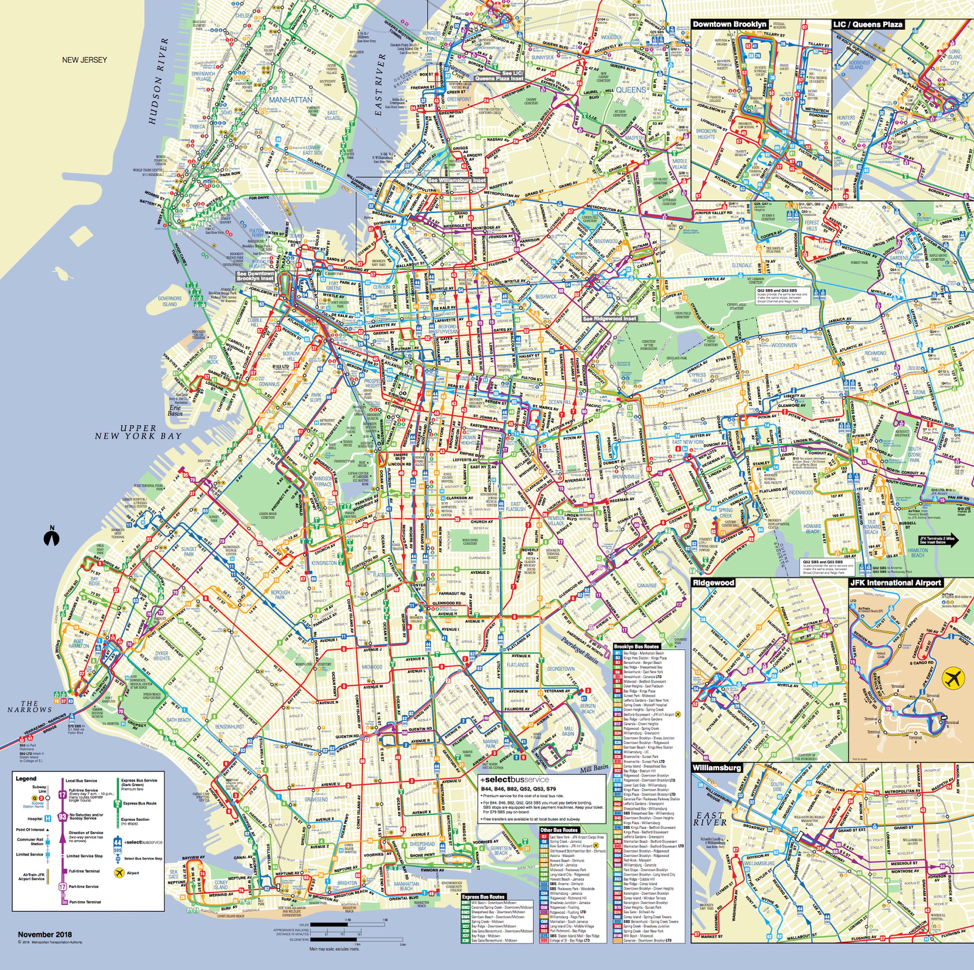

“Why would you go to a people’s institutions who hate your very existence by nature to provide you wellness?” Maya continued after her initial comments, visibly repulsed at the mere thought. I couldn’t help but to laugh in discomfort. Honestly, it sounded kind of ridiculous to me too now that she had put it that way, but I didn’t say so. In an Mbembean posture, Maya was clearly advocating for a kind of sovereignty which must exist beyond these institutions in places that are cultivated by communities and held by healers like herself. These kinds of places are peppered throughout Brooklyn, often connected by the tracks of the folks who frequent them. With each passing day that I made the trek from my apartment in Harlem to the café in Clinton Hill, sometimes backtracking a bit into Fort Greene for free community yoga or south toward the Flatbush apothecary, I traced the care network.

Brooklyn Bus Map © Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority

I begin with Tabatha of the Flatbush apothecary—a master herbalist, so to speak, who has trained many people in herbalism, some of whom are now a part of this care network practicing in Fort Greene, Prospect Heights, and East Flatbush. One day, a shop regular at the wellness café mentions an herbalism workshop that is happening this week at the community garden in East Flatbush. “It’s led by this woman Tabatha who owns an apothecary south of here. Y’all wanna go?” In Fort Greene, a former student of hers arrives at a local gallery and multipurpose venue to host a free meditation/yoga/breathwork/sound healing session for an hour. She is now a part of a collective that travels from venue to venue carrying a vision of sustainable Black life in the name of healing justice. They carry place with them as an embodied assemblage of knowledges, experiences, and subjectivities gathered from these respective sites of practice. Place travels in this way as a series of occurrences, and the healers set the rhythm through hums and chants and choreographed movements of the body.

One evening, the collective participates in an event in the multipurpose venue in which healers from around the city share resources and host workshops. Well into the evening, a member of the collective approaches two Black women to ask them in a hushed tone if they want to participate in meditation practice. “There’s a lot of colonial [read: white] energy in here,” she laments. And further, if it is clear that Black people and people of color do not need the meditation practice, she will cancel the session. They did not. Perhaps compounded with the tasks of place-making and space-holding, a healer may also necessarily be a guardian of space and to hold for whom it is intended. It is a radical exercise of sovereignty on the part of the healer to assert that “this space is ours”, that “our bodies are ours”, and to fortify Black communities from potential harm against the body by way of the micro-aggressive behaviors of the well-meaning; for “truth be told, you could no longer control those sighs than that which brings the sighs about.” This guardianship over safe space is an attempt to control that which brings the sighs about—a kind of preventative healthcare. So, they guard, and they hold, and everyone breathes.

Defining what it means to establish places of belonging is vital to any medical anthropological endeavor that seeks to answer questions about communal healing practices. If the healing of the Black collective body requires a reconstitution of relational infrastructures of care, communities like those found in Brooklyn are sites of significance as their constituents work to make, hold, and guard structures of belonging.

Symone A. Johnson is a PhD student in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Notre Dame. Her research explores how Black Americans in urban spaces employ modes of healing in their everyday lives and build communities around visions of well-being.

Please send your comments and ideas for Anthropology News columns to SMA contributing editors Dori Beeler ([email protected]) or Laura Meek ([email protected]du).

Featured Image: Symone A. Johnson

Cite as: Johnson, Symone A. 2019. “Making, Holding, and Guarding as Spatial Politics of Healing.” Anthropology News website, March 27, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1125