Article begins

This story is based on Aldo Anzures Tapia’s dissertation, “The Promise of Language Planning in Indigenous Early Childhood Education in Mexico,” winner of the 2021 Council on Anthropology and Education Frederick Erickson Outstanding Dissertation Award. Find out more about this annual award and the nomination process on the CAE website.

It was time for our midday break. Jacinto, a K2 student, stayed with me in the classroom, coloring his page before he left for his snack. As he was drawing in his notebook, he shared that he had “sueños feos sobre mi mamá” (nightmares about my mother). He dreamt that his mother died. I told him, “es una pesadilla, no pasa nada, y ella está viva, ¿verdad?” (It is a nightmare, nothing will happen, and she is alive, right?). He nodded his head. Angsty, he asked me, “¿maestro, por qué soñamos feo cuando vemos películas feas?” (Teacher, why do we dream ugly when we watch ugly movies?). He then stopped drawing and told me that he is sure that his mom works at the same place where I go when I do not come to the school and that “si la encuentra donde usted se va a trabajar, le dice que tuve una pesadilla, que estoy soñando feo, que se moría” (if you find her where you go to work, tell her that I had a nightmare, that I am dreaming in ugly ways, that she died). I told him that she will be back at night to his house, and he can personally share these concerns with her. He continued sharing that he was very worried that because he was not behaving very well, he was having nightmares or that the teacher or I could put him in jail. I told him that this would never happen. He seemed happy with this response and finished his drawing. (Field notes)

Most parents in Huaytsik (a pseudonym) work in the Riviera Maya (e.g., Playa del Carmen), a three-hour trip one-way if one has private transportation. Well-maintained roads and proximity to the Riviera have allowed large resorts to pick up workers in Huaytsik early in the morning, bring them to the hotels to serve as launderers, kitchen staff, and maintenance workers, and return them to Huaytsik at night. Economic remittances, housing styles, and ideologies about language such as the importance of English, are just a few of the forms of capital transported in these daily six-hour trips. Concerns related to parenting, such as child abandonment and schooling, leave parents and children emotionally as well as physically taxed. Jacinto and Yuri, his mother (all participant names are pseudonyms), were not exempt from this emotional and physical stress. Jacinto’s anxiety and fears during the school year made Yuri stop working in the Riviera and stay at home with him and his siblings. To not bring money to the household implied that there would be an economic burden to the extended family since now her siblings had to work extra hours in their hotels.

Huaytsik, the site of my doctoral study, is a Maya town of approximately 5,000 people in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo on the Yucatan Peninsula, and is part of Felipe Carrillo’s municipality, which has been described as the most Maya-monolingual municipality in the state. As has historically been the case in Indigenous communities throughout Latin America, this linguistic characteristic is closely tied to the town’s high rate of social exclusion and poverty. Between May 2017 and August 2018, I engaged in ethnographic and participatory research in a single-teacher multigrade Indigenous preschool (ages two to six) attended by 28 children. I accompanied Elisa, the only teacher and administrator at this school, and participated in the day-to-day aspects of schooling, complemented by my taking part in early childhood activities with the other four preschools in town and in informal early childhood educational activities that took place in the community. This ethnographic and participatory research provided me a window into the complexities of Indigenous early childhood education and helped me to bring into relief the personal stories often obscured by a field focused on school readiness, health promotion, and cost-effectiveness.

Since the 1990s, Maya communities have been moving from an agricultural economy to a cash-dependent one. This shift brought circular migratory waves from rural to urban areas, a phenomenon perceived by many as a mixed blessing: external employment in the town brings with it wage labor, but also a fear of cultural and linguistic loss. Huaytsik is not exempt from this circular migratory pattern, and Maya, amongst other Indigenous languages, is now more visible along the Riviera Maya, creating new dynamics in educational and familial arenas. Paradoxically, instead of taking advantage of the multilingual nature of the families, there has been a process of linguistic homogenization, where Spanish becomes the home language, which is further promoted by schools as it becomes the language of instruction in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous preschools. Moreover, rather than taking advantage of potential linguistic repertoires and Indigenous funds of knowledge, families and schools have opened their multilingual stance to English as a desired language to be taught from the early ages.

For the municipality’s education chief, as tourism is growing, Maya usage is decreasing. He does not just blame English as the reason for this, but also the way tourism is attracting Indigenous people from other states to migrate to Quintana Roo. Accordingly, Indigenous children are coming to the Indigenous preschools “con sus propios dialectos y esto afecta los perfiles de egreso. No hablan ni español, ni Maya y eso impacta mucho el perfil de los alumnos en el estado.” (With their own dialects and these affect the students’ exit profiles. They do not speak Spanish or Maya and this greatly impacts the student profile in the state.) He knows that schools are not prepared to receive these students as children come from “Chiapas, Veracruz, Tabasco, y son diferentes lenguas. Entonces, los niños van a la escuela, pero hablan español, pero también se comunican en su lengua, cada niño va aprendiendo algo.” (Chiapas, Veracruz, Tabasco, and they are different languages. Thus, children go to school, but they speak Spanish, and also they communicate in their language, each child is learning something.) He understands that children are learning something, but the target Indigenous language is not part of it:

En todo Mexico no se pueden reprobar a niños de primero y segundo grado, grave ¿por qué? Este niño va a estar arrastrando toda la primaria. …En México se dice, “a mí me vas a entregar un porcentaje bueno de educación para que yo te de dinero para el fin de año”. Nos condicionan. ¿Qué tienen que hacer? Maquillar e inventar. Las estadísticas, dicen los japoneses, son engañosas. Como decía un cronista, “se parecen a los bikinis, muestran todo, casi todo, pero no muestran lo principal.” (In all Mexico you cannot fail children in first and second grade. This is a serious matter, why? This child will be trailing behind his whole primary education. In Mexico it’s said, “You are going to deliver a good educational percentage in order for me to give you money at the end of the school year.” They condition us. What needs to be done? Make up and invent data. Statistics, the Japanese say, are deceiving. As a chronicler said, “They are like bikinis, they show everything, almost everything, but they do not show the main part.)

Since there is lack of resources, people lie about how well Indigenous schools are doing, which perpetuates the deficiencies many of these schools embark on, such as saying that they are teaching Maya, when they are not. Yet he knows that even if they want to teach Maya, the migratory situation will hinder it, as the language environment in the region is unique and complex when compared to the rest of the country.

Yuri tries to speak Maya to her children as much as possible, but with the experience of being engaged in the seasonal migration to the Riviera, she understands that speaking Maya and Spanish is not enough, “porque ahorita cuando salen a trabajar es acá a Playa, a Cancún y es donde se habla más la maya y ahora lo que piden es algo de inglés. Poco a poco se ha ido quedando atrás la maya.” (Because right now when they go to work it is here in Playa, Cancún and that is where Maya is spoken and now what they ask for is English. Little by little, Maya has been left behind.) These assertions surface the intertwining dynamic of the potential equality and actual inequality of languages, where there are glaring power differences among languages in society in the face of the linguistic dictum that all languages are potentially equal.

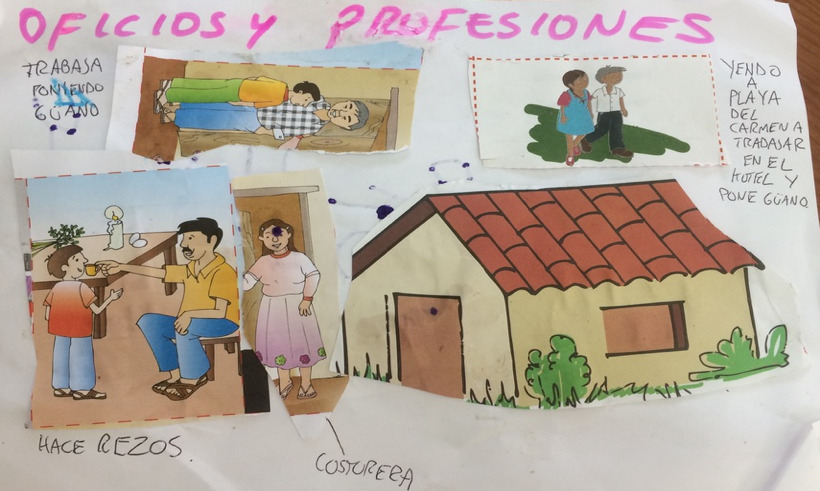

Just like Jacinto, Zara also imagined where her mother was working or what types of jobs she was doing. On one occasion, Elisa was teaching about jobs, a topic that motivated them to talk about the jobs their parents have in Playa del Carmen and Cancún. The aim of the activity was to identify, cut, paste, and describe the different jobs in some worksheets. When I asked Zara to explain what she cut out and pasted, she told me that in her pictures “la gente está yendo a Playa del Carmen a trabajar en el hotel y poner güano [para los techos]” (the people are going to Playa del Carmen to work in the hotel and place palm fronds [for the ceilings]). She later added that they also go “para hacer magia y rezos” (to make magic and prayers).

Zara was one of the children who felt her parent’s absence the most and always asked if I was going to Playa del Carmen or if I had left my children, too. Zuzy, her mother, recognized Zara’s sadness, and told us that she feels a lot of pain every time she leaves, and does not want Zara to think that she does not love her. After the 2017–2018 school year ended, Zuzy decided to take Zara to Playa del Carmen with her. She preferred for both to be together even if the adaptation to Playa del Carmen could be dangerous and a challenge.

As a researcher, I struggled with the idea of being separated from one’s children at such a young age. How great must the need be for you to leave what you love the most? Parents understood that I was interested in preschool education and Maya language, but I soon realized that migration was the utmost factor that affected the way education was lived inside and outside the school, and thus how Maya was eventually transmitted. As tourism and migration bring Indigenous children from all over Mexico who speak languages other than Maya to the peninsula, an important question remains: What becomes the function of Indigenous modality schools to a multilingual population when they can barely provide services to their own community’s languages? My research sheds light on how regional educational policy needs to consider the fact that Indigenous preschools placed exclusively in rural communities fall short of the ideal of serving all Indigenous children, when many of them and their families are migrating to urban areas.

Parents engaging in daily migratory patterns are fundamental to creating the paradisal Maya experience where turquoise oceans and Maya ruins come together, while they are consistently excluded from them. Indigenous preschools, even as they are ill equipped, are places that have operated as safe spaces where parents leave their children and where families’ anxieties are managed as affections are displaced. Moreover, Indigenous preschools are potential spaces for Indigenous multilingual ecologies to develop. Thus, it is important to consider how even though Indigenous modality schools in Quintana Roo might lead to nothing in terms of the teaching and learning of Maya, they nevertheless create caring spaces for parents and establish milestones for the future implementation of Indigenous language policies. Because of that, they should be extended to urban spaces that are receiving immigrants from places that are different to the peninsula. Once established, the defense and strengthening of these educational milestones will depend on the support of parents and the astuteness and preparedness of teachers, supervisors, and education chiefs as they navigate the politics of tourism, migration, and education for the Indigenous population and immigrants.