Article begins

Nuclear energy is a serious business for adults. We talk about board meetings, security protocols, politics, innovations, scientists, and more politics. But what if nuclear energy is also about children’s play?

In Japan, nuclear energy is kid stuff. Children do not just learn about it through textbooks but are invited to actively play with it. They grow up surrounded by the anime and manga of Astro Boy, draw posters and craft slogans to celebrate the national day of nuclear energy at school, and play board games to quickly build and safely run reactors in emergency scenarios. Nuclear energy exists with and through them all the time, shifting forms from plastic figures, homework assignments, stationery items, and birthday gifts. Making nuclear energy “friendly” to children, or friendly enough “for even a child to understand,” is the goal of PR campaigns and advertisements. In this fun, cute, and cheerful world, otherworldly materials like plutonium (of spent fuel) or tritium (of contaminated water) are transformed into “Pluto-Kun” and “Mr. Tritium”—for children to make friends with.

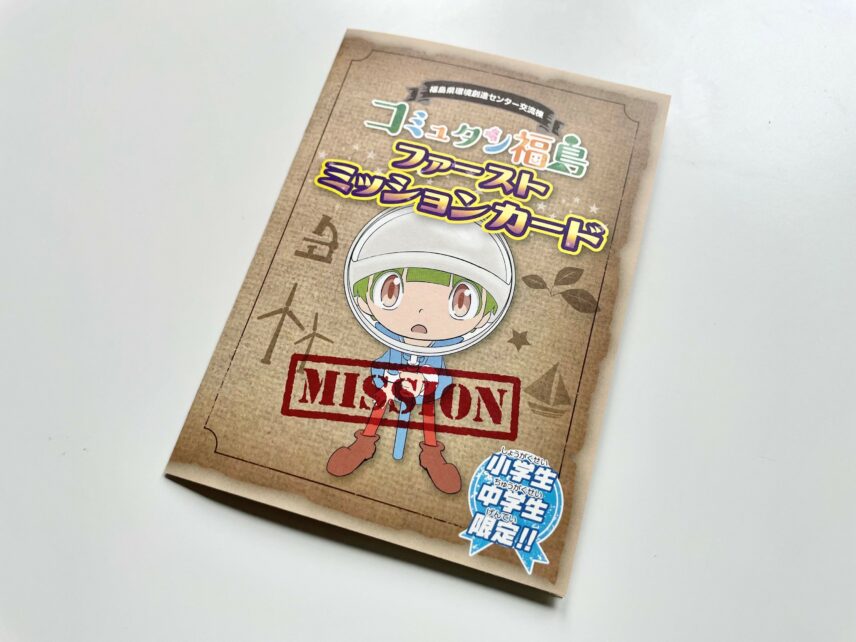

In post-disaster Fukushima, children are constantly encouraged to participate in playful engagement with nuclear things. They venture outside to try Geiger counters for science class, play ball on soccer fields in reopened towns that were previously off-limits areas, cultivate rice with sleeves rolled up for agricultural sustainability lessons (for chisanchishō, “local production and local consumption”), stand on tiptoe to pore over a cloud chamber (a particle detector visualizing the movements of ionizing radiation), or wave controllers to “catch” radiation at an environmental education center—crowded with school children on field trips since its opening. They often come home with more things to tinker with, including stickers, sketchbooks, candies, and badges—decorated with characters of a bulb, a reactor, or an atom. Friendliness matters more than lessons.

Most of the time, it is not entirely clear how “nuclear” these things or activities are. And for that reason, for anthropologists, they are good to play with.