Article begins

The night was black as pitch. My two-year-old daughter wandered the deck of the small sailing yacht when, suddenly, I heard a splash. I raced toward the sound and, fully clothed, dove into the sea. Swimming in the dark, I worked my way up the side of the hull, arms outstretched. After what seemed an eternity, I felt her wriggling body, carried her back to the surface, and returned her to the boat. She was in the water by herself for only a few seconds, and by the time I set her on the deck she chattered happily about the thrill of “swimming underwater.”

That was our last night on Nukumanu Atoll, a Polynesian outpost near Papua New Guinea’s eastern border. My wife, two young children, and I were completing a year of ethnographic research in the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. We were expecting a ship to take us back to the provincial capital when, to our amazement, the yacht appeared with friends we had met months before. They were on their way to the United States, stopped in to check on us, and hosted a farewell dinner. Little did they know that it would lead to one of the most harrowing encounters in my 50 years of field research.

I entered anthropology hoping I could make this world a better place. I knew that some of history’s most brilliant minds had tried without success to resolve our many social problems—stratification, exploitation, crime, war, racism, the list goes on—and thought it might be helpful to escape my Western mindset. In my second semester at the University of California, Berkeley, Gerry Berreman’s “Introduction to Cultural Anthropology” opened the path.

Later, as a University of Chicago graduate student, I sought a field site where cultural understandings and social structure would stand in vivid contrast with my own. I also wished to find a place where I could enjoy the natural world. My father had taught me to hike, swim, paddle, sail, and fish. I learned the wilderness could be my home, and animals around me were my friends. As I considered the options, a remote, largely unacculturated Polynesian island appeared irresistible. Life would diverge dramatically from anything I’d heretofore encountered, and the idea of living off the land and sea seemed perfect. Years before, I’d read Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon Tiki and, after seeing his depiction of French Polynesia’s Tuamotu atolls, wondered why he ever left.

My master’s research focused on the Navajo, far from the sea. Then, while I was working on my MA thesis, Raymond (later, Sir Raymond) Firth came to Chicago as a visiting professor. Firth was known for his pioneering work on Tikopia, a Polynesian outpost in the southeastern Solomons. I took a couple of his classes and spoke with him about potential field sites. In one such conversation, he declared, “… if you’re looking for a remote island, you might think about Anuta. It’s near Tikopia and is as isolated as they come!” Following that lead, in February 1972 I found myself en route to what was then the British Solomon Islands Protectorate.

Anuta is a half mile in diameter, rises to an altitude of just over 200 feet, and is 75 miles from Tikopia, its nearest populated neighbor. British authorities tried to send a ship each month, but often two or three months passed between visits. Since the Solomons gained independence in 1978, shipping has become less regular, with visits sometimes as infrequent as once or twice a year. When I arrived, I found one English speaker and several fluent in Solomon Islands Pidgin English (aka Pijin); otherwise Anutans communicated exclusively in their Indigenous Polynesian language. Raymond had given me some basic lessons in closely related Tikopian, so when I arrived, I had an elementary grammatical understanding and a working vocabulary of perhaps a hundred words. Fortunately, the senior chief assigned me to stay with his younger brother, Pu Tokerau, the island’s catechist and only English speaker. I owe my ethnographic success to him and the many patient islanders who struggled to instill in me a comprehension of their language.

Anutans taught me that an empathetic way of life is possible; a social order predicated upon mutual compassion and support can be achieved. Their prime value is aropa, a word with cognates throughout Polynesia. It signifies emotional attachment as expressed through sharing of material resources. Aropa is also the cornerstone of kinship; thus, anyone expressing aropa may be considered family. On that basis, I became taina (brother) to the senior chief and, four decades hence, my son was ceremonially elevated to a chiefly position. Like other Polynesian islands, Anuta is organized hierarchically on the basis of gender and genealogical seniority. Leaders are infused with spiritual power, known as mana or manuu. At the same time, their legitimacy derives from using that mana to ensure their followers’ well-being.

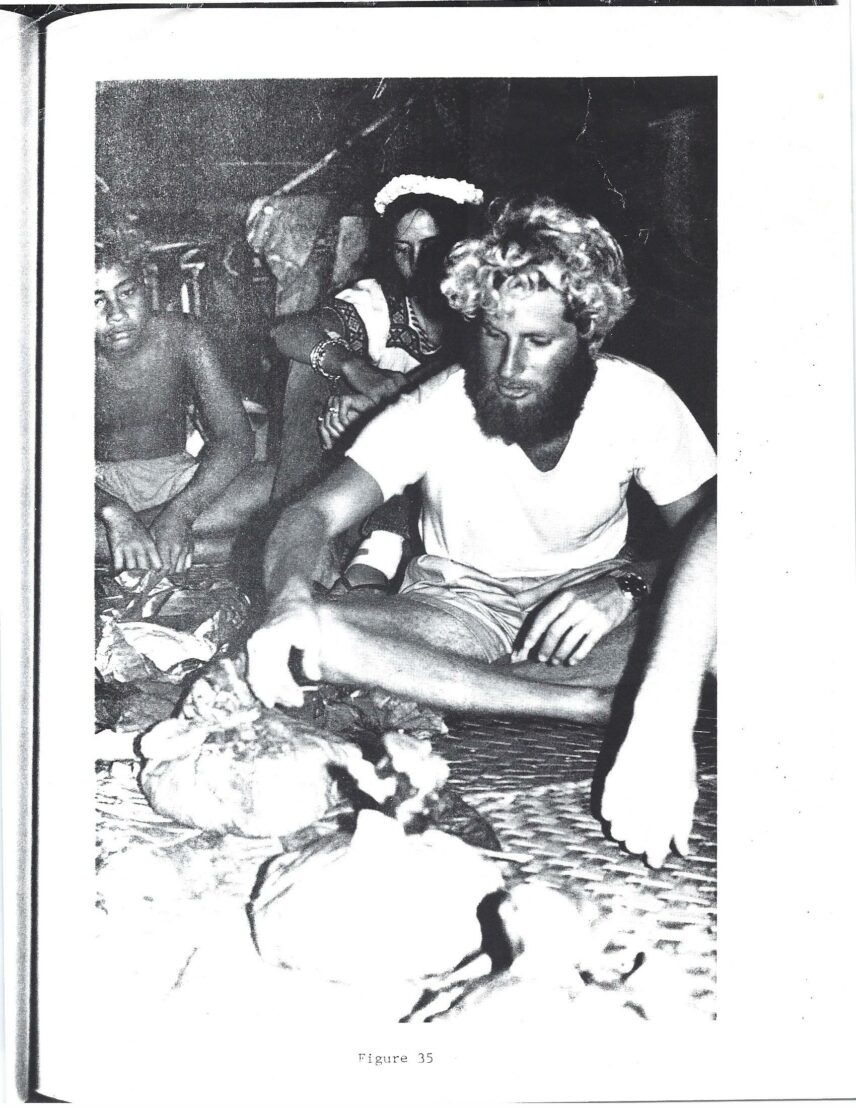

Anutans also helped me understand that life is complicated. Normally they treat each other with a kindness and respect that I have not encountered elsewhere. Yet mutual suspicion and rumormongering occur from time to time, and social stress can sometimes lead to mental breakdown. Two former friends of mine have died by suicide. Oral traditions are rife with tales of warfare. And, in 1973, I saw my hosts extort tobacco, rice, alcohol, and money from the crew of a Taiwanese fishing boat, a story I recounted in 2006 for the American Ethnologist. Still, the overwhelming ethos is of kindness and consideration, directed both toward guests and fellow islanders.

That kindness has touched many visitors. A Peace Corps volunteer who spent time with Anutans in the provincial capital in 1988 described the community to me as “magical.” And, in 2013, I accompanied a documentary film crew to the island. The Canadian-based group was working with the UN Convention for Biodiversity. Traveling aboard a 150-foot-long motor-sail schooner, the team spent three years calling at environmentally sensitive locations. Their itinerary included Anuta. However, gaining permission to work there proved a challenge, so they reached out to me. On arrival, they were greeted warmly, shown around the island, and treated to a stream of ritual feasts. We left to an exuberant dance, followed by ceremonial wailing. When at length we got back to the ship, the engine wouldn’t start. Thinking they might be delayed for weeks or even months, the boatswain let out an enthusiastic cheer, followed by “Right on!”

A centerpiece of my life has been its half century of connection with Anuta. I have studied and published on topics ranging from kinship to language, oral traditions, and cosmological beliefs, as well as economic and political “development.” During my first visit, I took part in a four-day voyage to Patutaka, an uninhabited island, in an outrigger sailing canoe, to hunt birds. That outing plus my long-standing maritime interest led me to investigate Indigenous navigation and spatial cognition, possibly the area in which I’ve made my greatest academic contributions.

My Anutan research has led me to fieldwork on other remote Polynesian islands: Nukumanu atoll in Papua New Guinea; Taumako in the eastern Solomons; and Atafu atoll in Tokelau, an archipelago north of Samoa. I enjoyed memorable encounters in all these field sites: some appealing; many stressful; each, in its way, rewarding. On Nukumanu, in 1984, my wife came close to dying of cerebral malaria but, thanks to care by local islanders, she made a full recovery. In 2000, I arranged to go back to Anuta with my son, but the Solomons’ international airport was closed thanks to a civil war (known euphemistically as “The Tension”), and we were stuck in Papua New Guinea. Eventually, I reached the Solomons by myself and spent two months with a friend in the capital, Honiara. Every night I would hear gunshots close behind the house.

In 2007–2008, I spent nine months on Taumako. Much of my time was passed in small canoes, and I participated in a nighttime turtle hunt where one of my companions was severely injured by a stingray. That was followed by a mad dash in a dugout to the island’s clinic while the victim moaned in agony.

Perhaps the greatest lesson from my fieldwork is that life is complicated. Everything is fraught with contradictions. To live close to nature and survive by fishing, gardening, or hunting birds can be fulfilling. But there is the ever-present risk of drowning in the sea, falling from a cliff, getting bitten by a shark, or being injured by a stingray. A social order built on kindness and compassion is compatible with human nature; yet a darker side is always lurking. That complexity is powerfully illustrated by Carleton Gajdusek of the National Institutes of Health, whom I met in 1972. He was leading a medical research team in the western Pacific, and I assisted in the project’s Anutan segment. Gajdusek was brilliant, thoughtful, eloquent, and energetic. Once, Raymond Firth described him to me as “a human dynamo.” In 1976, he won the Nobel Prize for Medicine for pioneering work on kuru. Years later, he was convicted of molesting a young Pacific Islander whom he had brought to the United States.

Through my years as an instructor, writer, commentator, and activist, I have drawn inspiration from my fieldwork. I’ve tried to instill in others an appreciation of human diversity and the chance to forge a better world―but also an awareness of the contradictions and complexity that will forever challenge us.