Article begins

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9 earthquake off the coast of Japan’s Fukushima Prefecture generated a tsunami that washed away whole neighborhoods and led to a series of nuclear meltdowns in the nearby Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. As a result of the ensuing nuclear contamination, towns near the power plant were evacuated and closed to residents. In some cases, as in the town of Futaba, this state of evacuation emergency lasted for over a decade, as tens of thousands of workers, including large numbers of migrants and unhoused individuals, collected and bagged contaminated topsoil and meticulously decontaminated local infrastructure. The ongoing process of postdisaster decontamination has resulted in hundreds of thousands of bags of contaminated topsoil and over a million metric tons of wastewater, and just as the disaster reduced once-thriving communities to ghostly memorials, it also led to a reimagination of the community’s economic and social infrastructure. The radiation that leaked into the air, the soil, and the water of these towns was invisible, leaving their physical infrastructure intact but decaying over the decade of abandonment. In their postdisaster reconstitution, the towns are living with disaster remains as predisaster houses, businesses, and vending machines lie undisturbed next to their postdisaster counterparts.

Over the past year, I have been spending time in Fukushima towns like Namie and Futaba, investigating how such communities are reimagining local revitalization, not just in terms of the nuclear disaster but in terms of broader socioecological instabilities. For example, Japan’s super-aging demographic crisis, (over 30 percent of the population is over 65 years old) is linked to severe rural depopulation and tax-base depletion, thus restricting resources for infrastructure repair and amplifying the effects of ecological disasters. The emptiness of these towns—the deserted streets and parks—is thus part of a broader story about what futures are possible for Japan, as ecological disasters are expected to increase in the coming years and as the demographic crisis is creating a shortage of human workers across core industries. Rather than being outliers, these towns are suggestive of the ways Japan is adapting to a shifting socioecological landscape via transitions toward new energy and manufacturing technologies that can function “without life,” fully mechanized and unoccupied.

Buffeted by coastal winds, summer in the hamadoori “coastal region” towns of Namie and Futaba shimmers with heat under wide blue skies. Hamadoori culture is closely tied to fishing, and though the industry remains decimated, local fishermen like Kyosuke continue to fish the waters of hamadoori bays. They are proud of the region’s resilience but fearful for the future, as the Japanese government releases treated irradiated water from the nuclear plant into the surrounding ocean, largely ignoring local and international environmental concerns. Even as it deprioritizes these “human” voices, the government has offered significant support for nonhuman infrastructure development like the Futaba Innovation Coast, incentivizing companies to open offices in Futaba or to build factories like the Super Zero towel factory. These spaces are often empty of actual workers. Visitors tour the Super Zero factory, purchase towels at the gift shop, and eat in a chain-brand café, but the factory itself is highly mechanized. The emphasis on forms of recovery and resilience that do not require or can ignore human presence is also evident in Futaba’s solar farms, which repurpose the town’s rice fields. The fields lie fallow, since residents are prohibited from farming them. Indeed, solar farms like those in Futaba are proliferating rapidly across depopulating regions of rural Tohoku—forms of economic and ecological resilience that do not require human life.

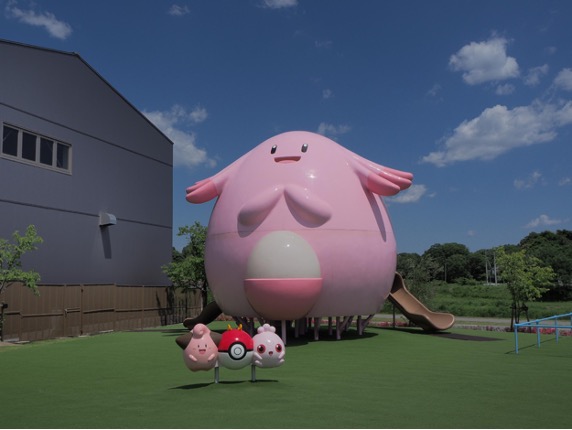

Often empty, too, is Namie’s central gathering spot, a michi no eki (roadside station). While most roadside stations are positioned alongside main roads or highways, the Namie station is close to the center of town and features a Pokémon-themed playground, though given the almost complete absence of children in the towns, the attention that it attracts is more often from tourists and fans. However, an overpass tunnel next to the Michi no Eki hints at a different story. Hidden from view, the image of a small teruteru bozu, a talisman said to ward off the rain, emerges from inside an artist’s tag. The black, red, and white of the graffiti contrasts sharply with the bright pink of the Pokémon in the official park only a few meters away. It suggests that there is another form of community emerging in these postdisaster zones, part of a larger phenomenon of individuals moving to places like Namie and Futaba to look for a different way to live, a way of living with disaster, in the place where disaster is ongoing.

Sarah Muir and Michael Wroblewski are the section contributing editors for the Society for Linguistic Anthropology