Article begins

Notes on farm work in a rural town in southern Turkey.

Çağla Ay was awarded the 2023 Photography Prize from the Middle East Section. In this piece, she brings us into her fieldsite of Finike.

Oranges grown in Finike, a small ancient town in southern Turkey, are known as Finike oranges, and are famous in the domestic market for their distinctive taste. Oranges are curious beings, not only because of the symbolic values attached to them and their economic value as the most cultivated commodity in town of Finike but also because they shape the meaning and materiality of the practices they are entangled in. Their vitality becomes most visible in attempts to standardize them and in their (re)production.

As the photographs above illustrate, I have been investigating the oranges in Finike as closely and as remotely as possible, using the visual technology afforded by a wildlife camera and a drone. Yet the significance of oranges for the town of Finike and its dwellers, human and nonhuman alike, are visible even to a stranger’s eye. As an interspecies relation, this human-orange entanglement is manifested everywhere from the roadside signs that welcome visitors to the “capital of orange”, to the citrus trees that seemingly enjoy every small corner in town. Since 2021, I have been conducting ethnographic research in Finike as part of my multisited dissertation research funded by a Wenner-Gren Dissertation Fieldwork Grant and American Research Institute in Turkey (ARIT) Research Fellowship. In this research, I have been moving across orange groves and citrus-processing factories of various sizes, local government institutions, public and private events, farmworkers’ settlements, and local fertilizer and pesticide shops, among other places.

Local Turkish as well as Kurdish and Syrian farmworkers work in Finike’s orchards and citrus-processing factories. Oranges’ botanical characteristics inform the materiality of their farmwork: they shape how and when picking should be done. Most farmworkers are tasked with picking 40 to 50 boxes of oranges in any given workday, and the majority of the time they do the picking with their hands. “It is a lot faster this way” (Böyle daha hızlı oluyor), Ahmet, a Kurdish farmworker in his 50s, told me while picking an orange with his right hand. As he picked the orange from the tree, he cut the thin branch tying the fruit to the tree, leaving a small hole on the orange’s skin. This hole would expose the fruit to air, light, moisture, temperature, and possibly microbial growth, ultimately changing the fruit’s skin, color, and smell—a condition many farmers and farm workers describe as early rotting (erken çürüme).

Thinking that handpicking might shorten oranges’ shelf life, which seemed an obvious threat for farmers and farmworkers in Finike, I asked Ahmet if they take any precautions against it. Holding the orange he had picked in his hand, he took another from a basket on the ground. The only difference between them seemed to be the green crown on the latter. Ahmet explained that an alternative to handpicking is to cut oranges with scissors. “When cut with scissors, a small, green, star-shaped stem exactly like this remains on the orange. When you harvest this way, the oranges’ shelf life becomes longer” (Makasla kesildiği zaman portakalın üzerinde ufak, yeşil, yıldız şeklinde aynı bunun gibi bir sap kalıyor. Böyle hasat ettiğinde portakalın raf ömrü daha uzun oluyor). Because it slows down the picking process, however, the workers end up picking fewer fruits with scissors on a workday. For farmers and factory owners who want to complete a harvest as quickly as possible to avoid paying more daily wages (that is, cutting down labor costs), handpicking is the preferred farmwork method in Finike.

To ensure the maximum shelf life for these oranges with exposed bellies, factory owners and orange producers aim to ship the oranges the day they are harvested and processed in the factories, where they are washed, sized, and waxed. Factory workers, moving at the pace of the assembly line, ensure the loading of the processed oranges onto the shipment vehicles the same day they are prepared. Time, labor, and oranges’ material properties thus correspond in curious ways in Finike, through the attempts to produce standardized oranges and standardize orange production. They are reflected upon the disparities in the agricultural labor sector, attempting to pace farmworkers’ bodies.

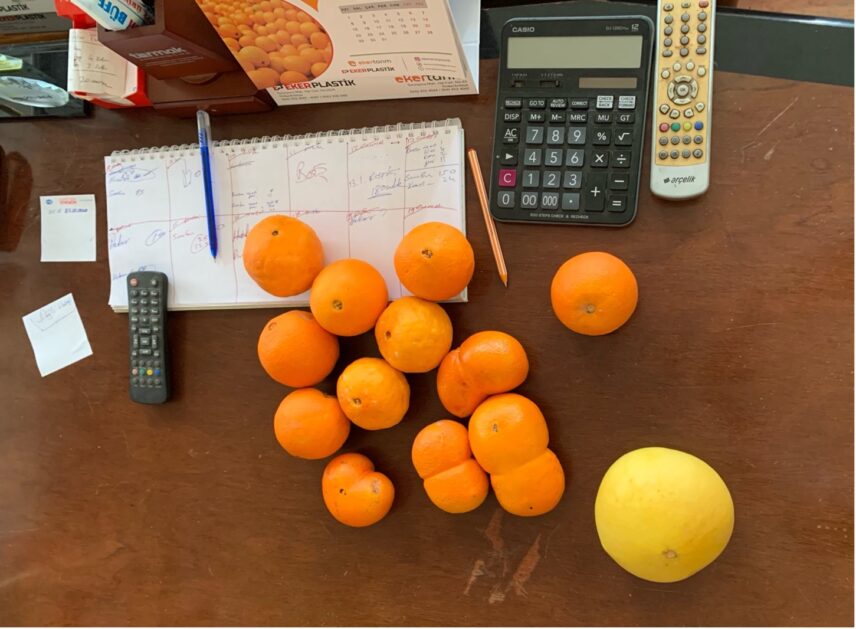

Meanwhile, like many other business owners, a factory owner I visited in Finike does not include “nonstandard” oranges in his estimations of how much his produce would make. On his table lay oranges he decided not to ship. They were incalculable—that is, not included in his calculations—because they grew out of the standardized agricultural production, and there were only a handful of them. Catching the growers and farmworkers by surprise, the rare form of twin oranges, however, quickly becomes part of a cultural exchange that is simultaneously monetary. Farmworkers collect twin oranges to demand extra money, explains the factory owner with a smile on his face, saying that they would bring fortune to his business. For workers who are familiar (enough) with the factory owner, twin oranges thus allow nontraditional work relations with their unexpected form, attributed to good fortune and sold for an additional daily wage. Oranges grown in Finike, thus, are not mere accessories to the production systems that are structured around them: their vitality intimately informs, and at times leaks beyond, the attempts to standardize them and their production.

Timothy Y. Loh is the section contributing editor for the Middle East Section.