Article begins

Between November 2018 and May 2020, as part of my dissertation research on humanitarianism and migrant futures in Turkey, I moderated Turkish language courses and mixed-media arts sessions at the informal community centers of working-class Syrian, Egyptian, Palestinian, and Iraqi migrants in Istanbul. A common theme arising in our gatherings was mobility. Particularly, migrants arriving from the eastern borders of Turkey experienced spatial control and stark inequalities in mobility compared to Turkish citizens and white tourists. These asymmetries were exacerbated during the pandemic, revealing their entanglements with race, colonialist alignments, and social class.

The happiest moment for my research collaborators was on a day in late December 2019, when Syrians in a community center in Esenyurt, Istanbul, learned from one another that they could now get intra-Turkey travel permits through an e-governance website. The system, which makes an online service feel like a gift, is a harsh one. Syrians are supposed to always reside in the city where their temporary protection IDs are issued. Otherwise, they can be deported. In this system, Syrians must apply for travel permits each time they need to go out of the city where they reside, showing proof of why they need to travel and providing exact dates.

Many migrants I have known, who fled injustices, tortures, and wars, have long been experiencing multiple forms of immobility that some of the more privileged of us can only associate with the COVID-19 pandemic. For them, seeing a newborn niece or nephew has been a dream. Visiting an ill relative or friend has required getting through painful and often dangerous bureaucratic processes. Going to a funeral to mourn with others for the loss of a beloved one has not been a possibility since they can remember. Yet while legal ambiguities and official discourses limit, if not criminalize, the mobility of working-class migrants coming from the eastern borders, white upper-class foreign tourists have often been formally welcomed with open arms to enjoy the “beauties” of Turkey—even in the middle of a pandemic.

“Enjoy, I’m vaccinated”

On May 13, 2021, the Ministry of Tourism and Culture in Turkey released an advertisement on Twitter, stating that all tourism staff were vaccinated to protect foreign tourists from COVID-19. The tourism workers featured in the campaign wear yellow masks. The message on the masks reads “Enjoy, I’m vaccinated” in a playful font, while the unmasked tourists in the same campaign enjoy the sea and hotels and are served beverages.

This promotional video inverts the often-hypocritical colonialist narratives of “saving the other” by assigning the frontline category of the humanitarian rescue narratives to the tourism workers. The tourism workers in the video look heroic, with pride in their eyes while serving/saving all-white tourists. The video represents Turkey as a “safe heaven,” playing with the phrase safe haven, often used in reference to safe spaces for oppressed and displaced communities. The video, therefore, portrays tourism staff as servers of the public good just because they are serving/saving the white tourists. It represents the efforts of the ministry as “double safety”: a combination of “sanitized resorts” and “vaccinated staff,” rather than the ways of profiting the tourism industry.

Moreover, an assumption underlies the campaign: that the only barrier preventing desired white tourists spending money and being mobile in Turkey was nonsanitized places and unvaccinated people. The foreign tourists who chose to travel to Turkey, accordingly, would be the most privileged ones who could enjoy high levels of purchasing power with limitless mobility regardless of a pandemic. Put differently, the mobility of these imagined tourists stemmed from their whiteness, imagined superiority to the locals, and higher social class. The fact that their mobility would be welcomed in the middle of a pandemic further unveiled these intricacies and the inequalities they produce.

The promotional video received many criticisms on social media, especially because the (im)mobility discussions were at a peak in Turkey at the time. A two-week-long curfew was in place for citizens and immigrants living in Turkey as a protective measure. Those who wanted to travel had to attain a travel permit documenting a vital necessity. Vaccination rates and vaccine availability were very low, at a mere 13 percent. The timing of the video’s release implied that limiting the mobility of locals created more “safety” for foreign tourists. Curfews and selective vaccinations could be implemented, all in the name of “saving” desirable white tourists.

When we contrast the desired mobility of white tourists with the experiences of undesired refugees in Turkey, the unequal mobilities intensified during the pandemic become even clearer.

Rendering undesired migrants immobile and spatially external

The Turkish government has recently placed emphasis on its hospitality toward Sunni Muslim migrants (particularly Syrians) in its official discourse. However, hospitality toward Sunni Muslim migrants differs from hospitality toward white tourists. Migrants are presented as temporary and spatially external through the written laws and in everyday bureaucratic encounters, rather than people to be protected through humanitarian safe haven categories. While Turkey is a signatory of the 1951 United Nations (UN) Refugee Convention, the refugee status is restricted to persons originating from Europe—a decision that, Kemal Kirişçi (2001, 74–75) has interpreted, was made to provide official refugee status only to people fleeing communist persecution from Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. This geographical scope clearly aims to prioritize neoliberal anti-communist expansion by integrating white refugees, rather than to protect human rights for all.

The government has not lifted such geographical restrictions notwithstanding the political shifts and recent influx of Syrian and Afghan refugees in Turkey. Therefore, people coming from the eastern borders of Turkey, depending on their nationalities, have very limited options: they can (1) find a way to settle in a third country through their own means; (2) apply to the UNHCR for refugee status and asylum which takes a painfully long time; (3) stay in Turkey as undocumented migrants, hoping to make a living or to save money to go to Europe (as in the case of many migrants from Afghanistan and Iraq); or (4) receive “temporary protection” through a 2014 regulation, as in the case of millions of Syrians.

These temporary and urgent forms of (non)protection force many migrants arriving from the eastern borders to stay undocumented and work informally. With about 1.5 million migrants working informally and increasing numbers of occupational murders (iş cinayetleri) every year, the Ministry of Family, Labor, and Social Services provides working permits to migrants extremely rarely. In the meantime, Article 54/ğ of the Law on Foreigners and International Protection implies that migrants working informally could be deported. These precarious legal conditions for migrants in Turkey enable politicians and law enforcement to manipulate migrant mobility unchecked and according to their own political agendas.

Manipulating migrant mobility

On July 22, 2019, the Istanbul governor announced that law enforcement officers were going to deport undocumented migrants and send Syrians who registered themselves outside of Istanbul back to their original addresses. At the time, as a Turkish citizen, I was also living in a city that was not my official place of residence. I was comfortable enough to not consider my official address. This did not lead me to have any difficulties with health care or housing, due to my status as a citizen. As a PhD student based in a US institution, I could easily frame my residence elsewhere as an honest misunderstanding. For a citizen like me, the only possible cost would be a fine, but for migrants, what I did could eventually cost their lives.

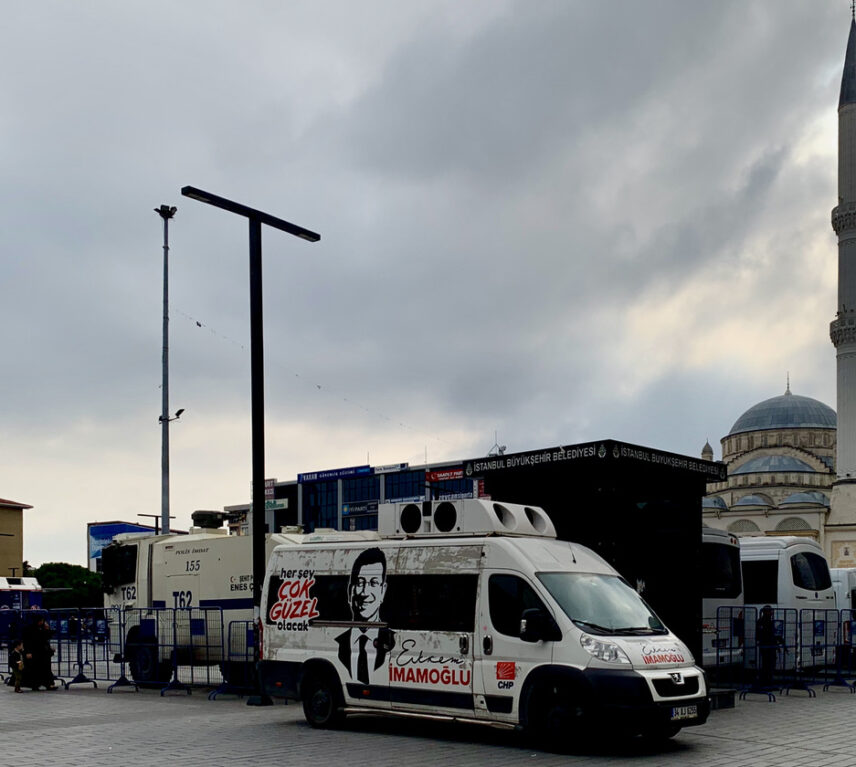

Immediately after the announcement, I started observing growing numbers of checkpoints and intensified surveillance throughout Istanbul. Some municipalities (like Esenyurt) had buses moving “voluntary” Syrians back to Syria, framing the buses as a public service to help Syrians. The number of police cars on patrol increased around majority-Arab migrant districts like Fatih and Esenyurt. The already-common ID checks by armed policemen soared on streets, squares, and the entrances of metro stations. An undocumented migrant would have to carefully reconsider entering these supposedly public spaces.

When Amir, a Syrian brother-in-law of one of my collaborators, went to the Migration Management Office in Istanbul in February 2020 to try to transfer his residence from Bursa to Istanbul, the officer there immediately initiated the administrative detention process. The police came and took Amir to jail. The judges gave Amir 15 days to leave Turkey and return to Syria. The decision was based on the Article 54/1d of the Law on Foreigners and International Protection: flexibility given to the judicial decision-makers in the law allowed the judges to interpret Amir’s mere existence in Istanbul, instead of where he received his temporary protection ID, as “threatening the public order and security.” While white tourists were welcomed to enjoy limitless mobility in Turkey, migrants like Amir were being punished, just for trying to be mobile.

Mobility inequality

Who gets to make decisions about the mobility and spatial presence of people? On what terms are these decisions made? And what forms of authority are exercised to add or remove the conditions of the right to exist and be mobile? Mobility is not an abstract category or a given, but legally and governmentally produced as an unequal part of everyday social life. The contrast between migrants like Amir and white tourists in the ministry’s campaign demonstrates that racism, colonialist alignments, and social class are intertwined and indispensable parts of differentiated mobility.

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced challenges for many people, rendering them unable to move from one place to another. Yet immobility has already been an everyday reality for many migrants, and for too long—especially for those coming from less fortunate circumstances. The conditions of the pandemic afforded governments and judicial decision-makers the power to deploy migrants’ labor, bodies, and existence as they wished.

Will people like Amir ever enjoy a voluntary form of mobility, instead of continued displacements and deportations? The answer will depend on whether the more privileged of us will keep turning a blind eye to politicians who oppress “the other” and take part in their forced displacement. We will see if the pandemic has taught us anything about rebuilding our ways of living together in more sustainable and equitable ways for all.

Author’s note: “Amir” is a pseudonym.