Article begins

Young Palestinians are taking center stage in Palestine right now. Through their social media campaigns, interviews, or creative writing and music, they are putting a new frame on the long-lamented “Israel-Palestine conflict.” My paper for the Middle East Section Best Student Paper Award focused on young Palestinians. Specifically, I asked: what can Palestinian children living in the refugee camps in Lebanon learn about the meaning and practice of resistance from reading an indigenous canon? Reading may undermine seemingly totalizing realities. It may introduce a gap between what is and what could be as demonstrated through the reading circles I portrayed in my essay. From the intimacies of a reading circle, a multitude of worlds can be explored. This practice can create a new world within and without spaces of exclusion; unconstitutional zones of being that violate the commonplace narrative on how to “be resistant” or imagine return, or a Palestinian future. Such experimental and imaginative engagements with the future generate a less constrained field from which new vocabularies may emerge.

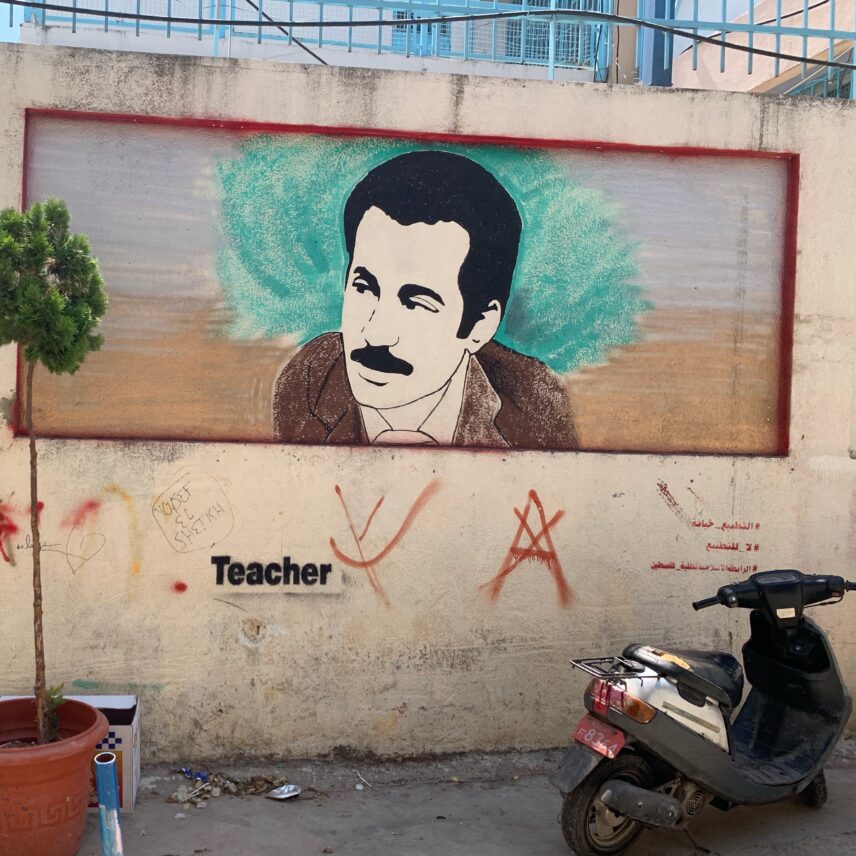

What is the relationship between readers and texts? Writing some time before 1968 in his study of Palestinian literature under Zionist occupation, Ghassan Kanafani, the assassinated Palestinian writer on whose work this paper centers, focused on the “persistent continuation” of resistance practices and tied them to the “language itself and speech of the Arabs of occupied Palestine.” It is in this essay that Kanafani coins the term “al-adab al-muqawama,” which literary theorist Barbra Harlow translates as resistance literature. Kanafani grounded his approach to “resistance” and “resistance literature” in an understanding of both the life from which they emerged and the prospective life they informed. This double-grounding locates resistance in dialogue with the reader’s living conditions and imaginative worlds. Therefore, to situate the memories and narratives of the past in present interactions and relationships, I practice “reading palimpsestically.”

Throughout my fieldwork at two Ghassan Kanafani Cultural Centers (hereafter GKCC) in the camps in Tripoli and Baalbek, Lebanon, I encountered material and conceptual surfaces that had been reused, erased, or altered while retaining traces of their earlier forms. Through this ethnography of reading practices that have introduced friction into haloed texts, I document the palimpsestic relationship in pedagogical practices of resistance literature. I show that readers of these texts continually push against reified meanings of “resistance” and open up yet unknown, unarticulated understandings of resistance that might well refuse, reject, or reform those advanced by prior generations.

How do we inhabit the space that a generation invites us into? How do we take the kind of distance from it that enables us to recognize both what we inherit and what we want to invent? An immediate problem confronting the present tense (and future perfect) investigation of resistance literature’s lives involves the conflation of resistance practices, with an ethnic-national memory community and culture of memory or a returning people, neatly summed up as Palestinians. Scholars have likewise argued that memory preserves Palestinian identity and therefore, essentially founds it. Some go so far as to promulgate memory as founding refugee’s resistance. In the eyes of institutions and governmental bodies and state structures “the refusal to forget the past” becomes their mechanism for legibility and relevance to outsiders. Such a logic manifests itself in pedagogical practices by foregrounding the importance of memory as the safe-keeper of identity; however, it may constrain a dynamic notion of resistance and identity.

Many third- or fourth-generation Palestinian refugees in Lebanon may no longer conceive of identity through inheritance, memory, or an a priori, fixed project of resistance. Or, they may no longer relate, at least directly, to a community of memory. Many of my own conversations with refugees in the camps support the importance of attending to the rapidly changing social and political imaginaries in the camps in Lebanon. In this context, the reading circles focusing on Ghassan Kanafani’s texts suggest ways to move from learning a temporally, territorially, and grammatically bounded genre of resistance to engaging in proliferations of resistance.

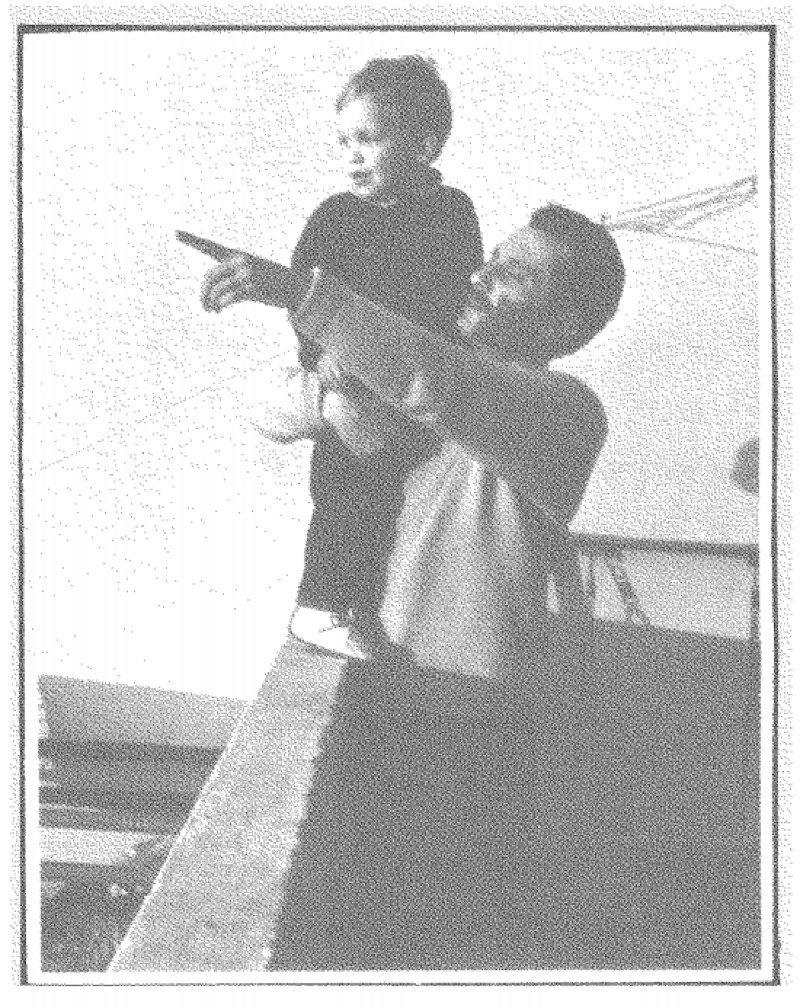

One story my interlocutors read was Kanafani’s Returning to Haifa (A’id ila Hayfa’). Set in 1967, Kanafani’s protagonists, Sa’id and Safiyeh, are allowed to revisit their home in Palestine—now named Israel—from which they were expelled in 1948. During their escape, they left behind their baby, Khaldun. They now find their baby was “adopted” by a Jewish settler family and renamed Dov. Dov, now 19, has just joined the Israeli army. He disavows all relationality to his biological parents, asserting that blood defines nothing. After all, he announces, “The human is a cause.” Surprised, Sa’id avers that, ironically, he was thinking the same thing upon realizing that he was foolish to long for Khaldun, now Dov. Dov’s disavowal of Sa’id’s patrimony reveals to Sa’id that patriliny as the form of relationality is no longer possible—or maybe never was. Patriliny assumes that one is captured for a body that is always-already Palestinian, that is, already in a stable form. Sa’id turns his attention to Khalid, his second son still in Lebanon, who wants to join the freedom-fighters who organize around the idea that “The homeland is the future.” He suddenly feels a strong urge to return to his son in Lebanon and cry on his shoulders, “reversing the roles of father and son in some unique, inexplicable way.” The reversal of the roles of father and son mirror Kanafani’s warning against melancholy: the past must rely on the future, and not the future on the past.

Karim, a 13-year-old participant in the reading circles at the Kanafani center in Beddawi, read the novella in a way that produces the conditions for the alteration, interpretation, and contestation of the past, and for the possibility of intervention and invention in the future. When I asked Karim what he makes of the sentence “The human is a cause” in Kanafani’s text, he responded:

I think…what is a land without its people (al-sha’b)? What is “our cause” and “the resistance” if we aren’t a part of making it? Like the Nakba isn’t finished, neither is the cause [metel ma el nakba manna khalsa, el qaddiya manna khalsa]. We students are learning it here, but also we are changing it and expanding it. [nahna el tolab ‘am nit’alima bas kamena ‘am min ghayera ou ‘am min wassi’a] I think, the human, he is the cause. Nothing else.

So, the short answer is “nothing else.” The full quote from Kanafani’s text that Karim references disenchants the whole patrilineal idea of inheritance and suggests instead an alternative grammar of relationality, not a blood relationality but a commitment relationality, not one of descent but of studied engagement: “Now I know, better than anyone, that man is a cause, not flesh and blood passed down from generation to generation like a merchant and his client exchanging a can of chopped meat.”

Karim’s reading acts as a negation of a negation (the missing land) that centers a person’s desires and needs, instead of territorial or nationalist calls to dream of a frozen Palestine. This decentering does not mean relinquishing the right of return. To the contrary, it means challenging alienation from “the cause” and “the resistance” and indeed the “land” —what do those terms even mean abstracted from the entities they purportedly signify? Through his reading of Returning to Haifa, Karim learns that identity (human) and culture (the cause) are not prescribed, grounded in the past, and extrapolates: “The Nakba isn’t finished, neither is the cause.” He finds the meaning of identity and culture in their relation, always unfolding: “We are learning it but also we are changing it and expanding it.”

Kanafani’s story pricks the reader’s notion of space in ways that make them rethink origin and return at once. Instead of generating a “law of return,” readers like Karim think about laws and their relation to praxis. They teach us to think about resistance not as an essence but a positioning. Through the voice of Sa’id, Karim continues our conversation and proclaims his rejection of prevailing forms of social belonging, pushing instead towards imaginations of the homeland as unforeseeable, uncaptured, nonconforming. His vision of a homeland necessitates the destruction of current dominant structures in order to imagine anew—perhaps one could call it an abolitionist vision of a future homeland. Karim reads resistance as something students are moving towards rather than a place they came from. He still sees himself as participating in resistance’s formation; yet it is a lively category, a category he will give life to, rather than merely inherit.

The reading practices surrounding Kanafani’s texts in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon suggest a way to enliven resistance practices while dismantling its reification and alienation. These practices stretched beyond dominant narratives and taught readers to view bodies in flux and becoming rather than through pre-formulated lenses on subjectivity, resistance, and Palestine. In turn, they direct us to the structural logics and genres of knowledge that constrain life. Further, they present us the pedagogical possibilities that conjure dynamic and transformative imaginations of the self, the future, and the world.

Above is an excerpt of Naye Idriss’ essay, which won the 2020 MES Graduate Student Paper Prize. The deadline for the 2021 prize has been extended until September, 2021; more information is available here.