Article begins

Jordan Peele’s Get Out revamped the horror genre with its skillful play on the idea that anti-Black racism is horrifying, and horror filled. The film centers on the idea that Black folks’ bodies are so desired and valuable that white people would bid on them, acquiring them for themselves. This grisly revelation comes late in the film, when the audience learns the party they’re watching is not a party at all, but instead a silent auction. The bidding occurs during a weekend when the Black protagonist is meeting his white prospective family, enduring what feels like an interview.

In March 2022, I visited the Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis, Indiana, where the Colts usually play. I was there to witness the public portion of the NFL Scouting Combine, a spectator to hundreds of players aiming to become members of what the professional league calls the “NFL family.”

Touted as the “job interview of a lifetime,” the combine is a five-day-long event for invited college juniors and seniors who hope to be drafted into the National Football League in April. It involves a brief orientation to NFL processes, interviews with team administrators and league representatives, chats with the media, opportunities to network with other prospects, and the part I was there for―a performance of on-field skills and drills. Interested spectators could reserve free tickets to enter the stadium on four different days to watch as football players were tested, measured, quantified, and analyzed in front of coaches, administrators, and media.

I was herded into the bustling stadium along with the trail of other attendees. Most were dressed in paraphernalia supporting their favorite teams and players, past and present. Before entering the stands, we were handed a program for the day and NFL-branded headphones. Putting them on, I learned that we could follow along with the commentators as they broadcast live on television.

The stadium was strikingly quiet. Without music or commentary coming through the speakers, there was a consistent hum of white noise―voices and machinery echoing through the bowl-shaped structure designed to seat at least 60,000 people. Players were down on the field with those organizing the drills. Fans were in the stands surrounding it. Team representatives enjoyed a synoptic gaze from the press boxes above. Bright lights, rigged cameras, giant screens, broadcast desks, invested scouts, excited fans―all of us gathered to focus on the gridiron.

“These are just a few of his measurables.”

―NFL commentator

Based on the programs I collected across different days of the combine, the 324 players in attendance were split into 12 groups, according to playing position. Each player received a number within his group and each group wore a certain color. As I made my way to my seat, the players in the group closest to the endzone, about 25 of them, were stretching to prepare for the first round of testing. Two other groups were mapped out on different sections of the field, already partaking in separate events.

Football depends on specialization; there are different playing positions for offense, defense, and special teams. Each position was allotted a particular time during the combine to guarantee that players would be tested alongside those with similar skill sets; each test designed to address position-specific challenges. A quarterback would be asked to throw the ball in a variety of high-pressure situations, while a running back would need to demonstrate his agility and ability to subvert tackles.

“He’s a white guy,” I heard the white woman beside me say, as she pointed to a name in the program that corresponded with one of the prospects down on the field. “There aren’t many. Only two in this group,” she shrugged before moving on to the next point of conversation with her companion. It was an astute observation, but unsurprising to anyone who follows college and professional football.

Half of all Division I college football players are Black, and non-white players account for 75 percent of the NFL―abstract statistics clearly visualized by an overwhelming majority of Black players down on the field. Further, because of racial stacking, which tends to racially segregate athletes by playing position, Black players were overrepresented in most groups. Thus, the combine is an event focused primarily on the potential of the Black male athletic body. This isn’t new. William Rhoden explains that the sports industry depends on “black muscle,” a note that underscores the physical labor required for the system to persist.

After a few minutes of self-guided stretching, players’ flexibility was measured. Shoulder, hamstring, groin, back, and ankle flexibility were all calculated. Next, the vertical jump measured reach, as players jumped up as high as they could to hit a flag, followed by the broad jump to measure explosion and balance by jumping forward. One after the other, in the order of their given number, players went through the required physical motions.

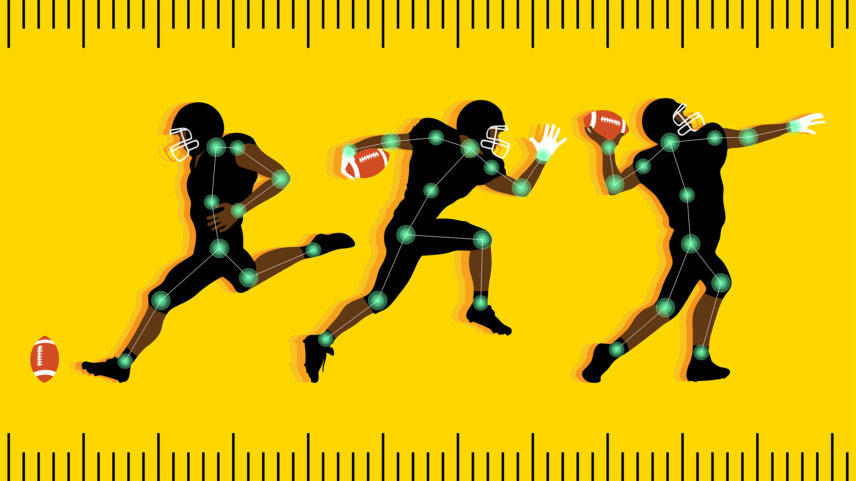

This was followed by the combine’s most recognized event: the 40-yard dash, colloquially known as “The 40.” Prospects are asked to run at full speed for 40 yards, twice, with their fastest time officially contributing to their record. Once everyone in the group finished running, equipment like cones, kicking cages, and standing and step-over dummies were scattered across the field to mark the various drills. Round after round, players proceeded through these tests. Here, they were expected to impress team scouts who were critiquing the minutiae of their athletic movements: how fast they run, how quickly they turn, how effectively they catch or throw the ball, how abruptly they stop, how precisely they shift directions.

These athletes, the best young football players in the country, have been preparing for this moment their entire college careers―many of them their entire lives. Embodied details matter. The drills at the combine present a snapshot of what those with power have determined will provide the best data to measure NFL potential, even though most of these events would never take place in this way during a real football game.

Scouts use a linguistic shorthand to reference an athlete’s personality and work ethic, but most importantly, how his physical body is “built” and how it moves on a field. These comments about players that reference their “above-average fluidity,” “size to overwhelm certain opponents,” and “huge hands with rare weight-room power,” for example, make up the few qualitative notes that mark strengths and weaknesses. Immense focus is instead placed on quantitative stats, including height, weight, arm length, hand size, bench press reps, and 40 time. By the end of the event, each player is reduced to a bundle of numbers. One single stat will determine their overall performance: a grade that signals a prospect’s alleged worth, value, and potential promise. This year, players were ranked between 5.52 and 6.81, a seemingly insignificant range that somehow encapsulated the performance of hundreds of players.

“Remember the bloodline in that family.”

―NFL commentator

What the fans in the stands were witnessing―up to 7,000 people on the busiest of the four days―was the public professionalization process of the amateur football body. These young men are deemed “student-athletes,” a notion touted as the cornerstone of intercollegiate competition in this country, even though its accuracy has long been challenged and deemed a fallacy because this business thrives on unpaid athletic labor. Due to their statistical overrepresentation in the sport, amateurism enacts tangible harms that particularly impact Black athletes. The potential to be drafted into the NFL presents an opportunity for these athletes’ efforts to finally and literally pay off.

Yet former players have called attention to the combine’s exploitative nature and racist overtones. Colin in Black and White, the 2021 miniseries coproduced by Academy Award-nominated filmmaker Ava DuVernay and athlete-activist Colin Kaepernick, made headlines because the first few minutes of the show strikingly compare the combine and the slave auction block. In his cowritten memoir, retired defensive lineman and Pro Bowler Michael Bennett also associates the event with slave auctions, troubling the ways that players are treated “like a potential porterhouse,” as their bodies are studied, poked, prodded, and objectified.

At the combine, players are dehumanized, talked about as if they are pieces of meat for sale, something that became clear as I followed along with the omnipresent televised commentary in my headphones. This quantifying of the Black body traces back to plantation slavery, as hierarchy between pseudoscientifically determined biological races was rationalized through measurements to highlight physical difference. Skull size, bone density, lung capacity, and nervous systems, among other anatomical features, were studied to downplay Black intelligence and stress Black laboring potential. This race science developed in a way that prompted scholars like W. Montague Cobb to write against the idea that Black athletes were biologically equipped to excel physically.

Sitting in the stands, watching the combine, one might be unaware that these myths of racialized sporting prominence have been dispelled. Here, predominantly Black athletes are evaluated on a number of physical skills and abilities to determine their value to NFL teams. It’s a form of speculation, a strategic calculus influenced by the number of draft picks allotted to each team, which teams need to fill certain positions, how much money can be spent to draft players, and which players’ bodies might hold up best under strenuous professional play. These decisions question the value of Black labor in the marketplace in a way that is disturbingly reminiscent of how Michael Ralph discusses the ties between slave insurance and life insurance. Black athletes are classified as property and treated as machines, argues Harry Edwards; their performing and productive bodies fuel the league’s capitalist imaginary, for as long as those bodies remain physically capable of performing.

Age matters here; these players were recently sitting in college classrooms. With over 300 players in attendance, 103 universities were represented, and 60 of those universities received invitations for more than one player. Some athletes had participated in major post-season games, called bowl games, played just a couple of months earlier. But consider games like the Goodyear Cotton Bowl Classic in Arlington, Texas, and the Allstate Sugar Bowl in New Orleans, Louisiana. These events are named with obvious but not-often-discussed references to the commodities that sustained the economies in these southern geographies through slave labor. This rhetorical choice is important because it signals that the past is not yet past, in the words of Christina Sharpe.

Such entanglements of labor, capital, and Blackness are supported by the media-fueled obsession with the Black athletic body. The combine has been televised since 2004 on the NFL Network, before moving to the more accessible ABC/ESPN in 2019. These broadcasts are accompanied by constant and cacophonous commentary and analysis from journalists and pundits and former players in newspapers, and on television shows, radio programs, podcasts, blogs, and news websites. Keep in mind that since these players exist in a liminal phase―no longer college players and not yet professional athletes―they are not paid for this labor. But the media frenzy surrounding both the combine and the draft acts as a monetized segue between the college football season―a billion-dollar industry―and the upcoming NFL season. It’s a never-ending, yet highly predictable, cyclical spectacle which lasts all year long and depends on laboring Black college-aged men.

“These guys are special. You just expect freakish things.”

―NFL commentator

The combine drew fewer spectators on the final day. Noting the strangeness of the quiet stadium, and curious about the experience without the commentary, I removed the headphones for the day’s first events.

Posted instructions encouraged fan interaction and support during all the drills, except for the 40-yard dash. Because of the attention required to precisely complete this task, one of the most important of the day, players preferred quiet. Without the commentary to tell me who was running or how fast their time was, I watched as players took their designated spot, got into the appropriate position, and started running. One by one, they lined up and were ready to go once the person ahead of them was done. The audience politely applauded after each player completed his run, each lasting between four and six seconds. The sound of our hand claps filled the building for the several minutes it took for every player in the group to complete the drill.

The 40 on that last day reminded me of the auction scene from Get Out. Numbered, yet nameless, Black athletes were paraded in front of attentive, yet faceless, white scouts, team owners, and spectators. The anti-Black sentiment at the combine mirrored that in the film, but here we were presumably watching someone demonstrate his full potential, rather than bracing ourselves for the terrifying finale in the film. Football dreams were supposedly coming true inside Lucas Oil Stadium. But this was occurring in a way that reproduces Katherine McKittrick’s conceptualization of a plantation logic: Black people are normalized as the commodities which help bolster the economic value of the NFL in a way that rhetorically links labor, violence, exploitation, and subjugation. The combine is just one striking example of society’s obsession with the productive Black body.

“Look at how he’s put together. That’s a big, strong man.”

―NFL commentator

I filled my camera roll with photos and videos of the different stations on the field. I didn’t want to forget what I was seeing. But revisiting them now, I’m moved by the effect of this technological capture. Uncontextualized, these are just unnamed Black men, bodies moving, performing, jumping, running, and catching on a football field. I’d managed to visually represent what Ben Carrington theorizes as “the black athlete,” a constructed and idealized man reduced to being recognized by what his hypermasculine, physically advantageous, unthinking, animalistic body can do. These men have now become an abstraction preserved in my cell phone and by the NFL’s official statistics of their performance. Franz Fanon might describe them as “objects among other objects.”

It’s no wonder, then, why Billy Hawkins wrote about the college sport system as “the new plantation” or Rhoden described Black athletes as ”forty million dollar slaves” or former tight end Martellus Bennett reconstituted the league’s acronym as “Niggas for Lease.” There’s an underlying focus on labor, exploitation, racialization, and anti-Blackness that is all on public display at the NFL Scouting Combine. Its eerie similarity to both a slave-trading past and a horror film in the present, is stranger than fiction. The James Baldwin quote applies: the combine is a clear example of history being trapped in these athletes.

Illustrator bio: An Pan, multimedia designer, illustrator, and culture lover. His works focus on decolonizing design, culture exchange, and Asian futurism. He enjoys traveling and doll collecting.