Article begins

In Yakutsk, hip hop can be poetic, nostalgic, and even subversive. What can this inventive genre say about language relocalization and maintenance?

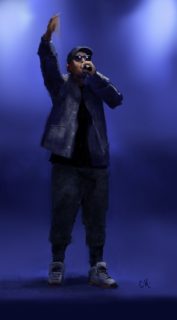

A crowd gathers at Muus Khaia (Ice Mountain), a popular restaurant and bar in Yakutsk, the capital of the Sakha Republic. Inside, the stage is backed by a banner reading “Sakha Underground Poetry” in graffiti-style English text. A cartoon graphic of a man wearing a parka, holding a boom box, and smoking a pipe accompanies a list of musical and literary styles in Russian Cyrillic: classical poetry, rock, country, rap, algys (blessing poetry), reggae, and Olonkho (epic poetry). The globally recognizable genres sit alongside those unique to the Sakha language. Then, the din of the bar quiets and an older man dressed in a traditional son (coat) steps into the spotlit glare. He performs an algys (blessing-prayer) in Sakha for the crowd, waving a white horsehair dejbiir hypnotically as his voice melds with the sounds of a DJ’s scratching.

The juxtaposition of local, indigenous verbal art with a foreign musical genre is neither forced nor haphazard, but seems fluid and organic—and also quite subversive.

Another performer takes the stage: a younger man in a hoodie and silver snow-blindness glasses, the living embodiment of the parka-clad figure on the stage backdrop. The sound of a khomus (jaw harp) fills the space, its droning twang flickering in and out of the mix. The man begins to rap in Sakha, his use of the uus uran (literary/artistic) register mirroring the older man’s algys. His words rise and fall with a cadence I have come to associate less with popular Sakha music and more with the oratory of elders speaking at festivals, rituals, and formal events. His lyrics speak to the power of ajylgha (creation/nature), the interconnectedness of humanity, and money’s perilous allure. He calls himself Khotogu Khomuhun (Northern Enchantment). I feel the potent merging of khomus and scratching, the echoic resonance of the rapper’s words. The juxtaposition of local, indigenous verbal art with a foreign musical genre is neither forced nor haphazard, but seems fluid and organic—and also quite subversive. Indigenous and minority languages are in a sometimes precarious and contentious position in today’s Russian Federation. To fuse the two genres is to engage in an act of creative revitalization, and push back against policies that seek to diminish the country’s linguistic diversity.

Speaking Sakha

Sakha is a North Siberian Turkic language spoken by approximately 450,000 people, primarily in Russia’s Far Eastern Federal District. Since the end of the Soviet period, it has enjoyed relative support as a co-official state language alongside Russian within the Sakha Republic, a subnational governing body within the Russian Federation. Despite a robust speaker population compared with many other indigenous minority languages worldwide, many speakers are concerned for Sakha’s continued vitality, especially under conditions of increasing federal nationalism and the acceleration of globalization with its attendant processes of linguistic contact and change.

During Vladimir Putin’s years in power, Russian nationalism has become increasingly associated with Russian ethnic nationalism, threatening to elide the multiethnic, multilingual, and multireligious characteristics of the country (see for example, Zamyatin 2016). In 2017, some acquaintances in Yakutsk confided to me that they felt this tendency becoming distinctly more noticeable following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. One significant domain in which federal support for minority linguistic (and cultural) freedoms has declined is the educational system; new policies are set to withdraw previous federal support for Sakha language education.

In Yakutsk and in other parts of the Russian Federation such language policy and intimidation is constraining the form that linguistic and cultural activism takes.

In April 2018, Sakha speakers rallied in a public square outside the Republic’s governmental buildings in Yakutsk, calling on local representatives to refuse support for the federal bill that would forbid schools from making Sakha language classes part of the compulsory general education curriculum. Turnout at gatherings was small, reflecting the size and scope of similar demonstrations at municipal government offices the previous summer. Friends who support of Sakha as part of the general education program voiced unease about attending demonstrations, citing backlash in other parts of Russia, speculating on the repercussions of taking part. In the Republic of Tatarstan in 2018, a citizen was charged with “inciting ethnic hatred” for writing social media posts that critiqued Russian federal powers (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2018). He had merely complained that the regional tax authorities and a bank did not provide Tatar language services and claimed this was an example of federal government discrimination against Tatar language and culture—despite Tatar’s co-official status with Russian in the Republic of Tatarstan.

In Yakutsk and in other parts of the Russian Federation such language policy and intimidation is constraining the form that linguistic and cultural activism takes. Scholars in Tatarstan note that claims to minority ethnic identity in contemporary Russia are more likely to emerge in speakers’ daily actions and choices rather than through public demonstrations dedicated to a specific cause (Suleymanova 2018; Yusupova 2018). The promotion of minority languages—especially in urban contexts in the Sakha Republic—is lately often accomplished through more indirect measures.

Hip hop’s accidental language planners

Hip hop in Yakutsk first emerged in the late 1990s as a Russian language endeavor; however, village-city migration helped reintroduce Sakha into urban domains and spurred a linguistic shift within hip hop. The increasing number of Sakha speaking youths in Yakutsk and the popularity of the music coupled with promotion of the language through television and radio encouraged the development of Sakha language hip hop as early as 2005. Local poet and musician Dorghoon Dokhsun, who organized the performance at Muus Khaia, is one of dozens of Sakha speakers creating popular music in the city; aside from the more established pop and estrada (stage music) genres, musicians innovate and play with hip hop, rap, and reggae, Sakha-fying it through their language use, stylistic intertextuality, and visual symbology. From the young hip hop artist Jeada (Gosha Vasil’ev) who emerged in the early 2000s with the ubiquitous hit “Min Sakhabyn” (“I am Sakha”) to the first Sakha rap-reggae artist and rising star KitJah, Sakha language performers embody the dynamic frontiers of linguistic and cultural revitalization.

Yet, when I began to follow the careers and performances of Sakha language musicians around 2010, I soon realized that they did not all set out with the primary goal of promoting Sakha or engaging in explicit language activism, nor did any of those artists I spoke with have more than a vague awareness of minority language hip hops elsewhere. These Sakha musicians are in a sense what sociolinguists Mairead Moriarty and Sari Pietikäinen (2011) call “accidental language planning actors.” Attending to the intersections of the global and local in language policy and planning means looking at the circulation of strategies and concepts explicitly tied to language revitalization, revival, and reclamation, but also to creative and artistic production created by those whose language work is less intentional. Sakha hip hop becomes a conduit for upholding and challenging linguistic norms while promoting Sakha language more broadly.

Such musical actions remind us that every act of continuing to speak a language—and create in that language—contributes to the ongoing transmission of that language as a whole.

Creative activities often organically become metaphorical spaces in which to challenge or support dominant policies and plans, linguistic or otherwise. In 2014–2015, Suus Bies Suus, a comedy collective led by Ayaal Adamov, produced parodies of both Russian hip hop and American pop songs and videos. They transformed the song “GQ” by the Russian rapper Timati from a profile of suave cosmopolitan gentlemen to one reveling in (and poking gentle fun at) Sakha rural life in “Moi khoton vsegda svezh” (“My Cowshed Is Always Fresh”); recreated Taylor Swift’s “Shake It Off” to show citizens dancing to survive -50°C Yakutian winters; and turned “Uptown Funk” by Mark Ronson (featuring Bruno Mars) into “Khotu uollatara” (“Boys of the North”), which highlights the indigenous ethnic diversity within the Republic and celebrates Siberian lifestyles. The relocalization of musical styles and songs creates a metaphorical space for the reclamation of indigenous communicative practices and genres; within these remade versions, local instruments such as the khomus (jaw harp) and dance styles such as ohuokhai (circle dance) are front and center.

Linguistically, however, these videos were controversial for many listeners as they were sung in a mixture of Russian and Sakha; dominant language ideologies among Sakha people focus on linguistic purity and the linguistic registers of Suus Bies Suus’s work disrupted these norms. Yet, in interviews Adamov explained that the mixing was not without intention. One reason for using both languages fluidly was to reach two different audiences simultaneously—local Sakha speakers who could appreciate the inside jokes as well as those who speak only Russian (especially outside the Republic). He hoped that Russian speakers might learn a bit more about Sakha life through their parodies (Ferguson 2019, 264–265).

Such musical actions remind us that every act of continuing to speak a language—and create in that language—contributes to the ongoing transmission of that language as a whole. Using popular music forms—those with foreign or global influences rather than solely “traditional” ethnic ones—can be a useful tactic for furthering local language use. Packaged in a global genre, Sakha language hip hop potentially reads as something “less Sakha” to an outsider, and therefore perhaps less likely to be construed as nationalistic or controversial. Simultaneously, a Sakha speaking insider may judge it suitably authentic, affording it transformative potential.

Protect your native language

Despite its roots in the faraway Bronx in New York City, to many young Sakha speakers hip hop feels both old and familiar at once. I often hear people compare hip hop to chabyrgakh, a Sakha tongue twister: sets of couplets employing particular alliteration, rhyme, and rhythmic patterns. If chabyrgakh is like hip hop, it follows for many that hip hop too is something authentically Sakha. On YouTube, a user created “Sakha Patter vs. American Rap,” a tongue-in-cheek bricolage rap battle between Snoop Dogg, Eminem, and Sakha speakers reciting chabyrgakh. Curated reaction shots from the American rappers reveal shock and disbelief at the chabyrgakh recitations, and the final score is displayed as the Sakha Republic: 2, the United States: 0. As commenter Jegor Kolesov wrote in response to the video clip, “How many young people are listening to chabyrgakh today? I think a lot more of our young people listen to rap, albeit in Sakha… but still it’s rap and not chabyrgakh. However, I believe that a culture should be active; it must absorb the best and develop in step with the times.” Sakha language hip hop could promote Sakha language among young people; for Kolesov, being “like chabyrgakh” could imbue hip hop with authentic value as well.

Charlotte Hollands. Illustration based on the author’s photographs.

The construction of authenticity is also deeply entwined with language choice, and how that language choice indexes adherence to dominant language ideologies in circulation. The ways in which hip hop artists reify those ideologies may also legitimize their not-always-intentional efforts as “good” language planning and promotion; at other times, this is where we can see language planning through hip hop happen much more consciously. Both chabyrgakh and Sakha language hip hop exploit the stylistics of oral poetry, using repetition, alliteration, assonance, and obligatory vowel harmony to great aesthetic effect, thus revalorizing Sakha language through these practices. In terms of code choice, the mixing of foreign languages—especially African American Englishes—with local languages is often seen to be a part of producing authenticity in global hip hops. Yet, many Sakha rappers tend to subvert this expectation as well. Searching transcripts of 60 of Jeada’s songs, I found only 3 songs that contained linguistic items that would be seen as bivalent in English and/or Russian: reper (< rapper), mikrofon (microphone), and muzyka (music). The lack of non-Sakha-associated items—and adherence to stricter language ideologies in circulation—in the vast majority of his songs means that both the form and content of his work tend to be viewed as valid contributions to the goals of Sakha language maintenance.

Sakha language maintenance, is perhaps most explicitly expressed in a song by young musician InVent, who sings Kharystaa manylaa törööbüt törüt tylgyn (Guard, protect your native language). The song “Törööbüt Törüt Tylym” (“My Native Language”) incorporates Sakha proverbs such as Noruot küühe kömüöl kuuhe (The strength of a people is the strength of the river’s ice break-up), and expresses sentiments of nostalgia and belonging through language:

Ije üütün kytta ingerbit tylbyttan

With our mother’s milk we drink (from) our language

Bulabyn olokh oloror küühün

I find the strength to live my life

Sakhalyy sangalaakh kihilii majgylaakh

A Sakha speaking person is

Turugurdun örüütün

Forever blossoming

In closing, the algys, or blessing-poem genre is evoked, finishing with the word “dom”:

Sakham tyla en

My Sakha language, you

Keskillen keskillen

Will succeed, succeed

Dom!

Make it so!

Here, we see how not all language planning in hip hop is covert or accidental. The track is a powerful exhortation for Sakha speakers to use the language and draw strength from tyl ichchite (the spirit of language), the animate and living essence that many believe empowers their words; it overtly aligns both in form and content with dominant language ontologies, ideologies, and policies and becomes a vehicle for the expression of those attendant ideals.

Whether covert or explicit, in late-night performances on local stages or on YouTube and music sharing sites, couched in “underground poetry” and invoking blessings of elders, Sakha hip hop encodes language policy that can be heard anywhere.

Jenanne Ferguson is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Nevada, Reno, and author of Words Like Birds: Sakha Language Discourses and Practices in the City (2019). Her work focuses on language maintenance and revitalization in urbanizing spaces. A new project will examine the intersections of verbal art, politics, and emotion/affect in several contexts in the Russian Federation as well as the United States.

Charlotte Hollands is an illustrator, artist, and ethnographer who is fascinated with the power of hand-drawn images to reveal and describe complex truths. She is developing new ways to use illustration within social science research and is currently completing her first graphic non-fiction book, written by Alisse Waterston.

Cite as: Ferguson, Jenanne. 2019. “Rapping in Sakha.” Anthropology News website, September 19, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1264