Article begins

Or when they encounter a space shaped by multiple relationships among industrial workers, activists, artists, labor organizers, and politically engaged local academics? How might graphic ethnography lend itself to this type of collaborative intervention? And what kind of an anthropology emerges from such open-ended efforts to reimagine our methods and modes of knowledge dissemination?

These questions have animated our collaborative ethnographic research project on the grounds of the Dita detergent factory in the city of Tuzla in northeast Bosnia-Herzegovina, which for a while became an epicenter of new labor politics in this postsocialist and postwar region. Founded in 1977, Dita was a part of a famous socialist kombinat SodaSo, the organizational structure for the chemical and mining industries which once dominated the local economy. After the war, this kombinat was split up and privatized, but many of its constitutive factories, including Dita, became sites of disinvestment and predation for newly-emerging oligarchies close to the political establishment. After the company was brought to the verge of bankruptcy, Dita’s workers organized to challenge the seemingly inevitable liquidation of factory’s assets. Insisting on the factory’s continued viability, they sought a means of restarting production and finding a new strategic investor that would help them save their firm and their livelihoods from total destruction. Thus began their multi-year, well-publicized struggle, which included a variety of tactics such as street protest, factory occupation, hunger strike, legal injunctions, and even a staged “exodus” from the country. Throughout this mobilization, workers and their union representatives were aided by a range of allies, including local student and activist organizations, sympathetic journalists, and politically engaged academics. This process thus ended up generating multiple forms of sociality and solidarity that amplified the political force of the worker mobilization, which finally culminated in the factory’s reorganization and resumption of production in 2015. Dita’s unprecedented reclamation in a country ravaged by unemployment and growing poverty made the factory synonymous with political possibility itself.

The exceptional nature of the Dita workers’ struggle attracted the attention of Larisa and Andrew, both of us long-term researchers in postwar Bosnia-Herzegovina. Trained as political anthropologists, we conducted separate ethnographic projects at Dita for several years prior to the start of collaboration. In 2017, working in concert with Workers University (Radnički univerzitet), a local collaboratory led by our activist-academic colleagues at the University of Tuzla, we joined forces to pursue a concrete goal: producing a graphic ethnography of the workers’ struggle to restart production. We wanted to investigate how and why Dita’s workers succeeded where others had failed, despite being beset by the same forces that destabilize or undermine other similar worker campaigns.

From the beginning, we felt that telling this story required a different kind of methodological arsenal and a novel representational format that could also appeal to the workers. This is what eventually led us to the idea of graphic ethnography—a genre that holds a unique place in popular culture and great historic appeal among various Bosnian publics. Comic books were an integral part of youth culture in socialist Yugoslavia, helping shape aesthetic and political sensibilities of entire generations, including those of the workers whose stories we wanted to tell. The graphic medium therefore made sense to our interlocutors as a narrative modality in ways other mediums did not. On our end as researchers, we were also attracted to graphic storytelling as a representational format that could convey the complexity of social relations and the colossal industrial environment comprising machines, materials, and people, all of which enabled the making of commercial goods and political possibilities. Having decided to take this plunge, we recruited our third coauthor and colaborer, Boris Stapić, a Sarajevo-based graphic artist who had already worked on several politically oriented comics.

Collaborative fieldwork

As anthropologists habituated to solitary fieldwork, our first foray into the field together was a novel kind of experience. We each entered our site positioned a bit differently based on our age, gender, background, professional capacities, and affective affinities. Larisa and Andrew already had established relationships with the workers, but those relationships were differently distributed based on prior interpersonal dynamics. As a Bosnian-born anthropologist, Larisa was capable of quickly opening lines of communication and building emotional rapport and trust, while Andrew was authorized to ask even the most schematic and elementary questions, without risking embarrassment or dismissal. Boris was, in his own words, “a new cookie”—a novel presence and a soft-spoken artist who was particularly effective in forging bonds with the more introverted workers and those who were primarily interested in his capacity to recreate their lived experience in the comic format.

We also worked in collaboration with three Tuzla-based research assistants, Azra Jašarević, Sanja Horić, and Haris Husarić, all of whom had longstanding relationships with the workers and with us, in addition to having professional backgrounds as researchers, journalists, and media producers. This copresence on site, each of us able to engage workers in a conversation, ask follow-up questions during the interview, and make our own observations, meant that fieldwork was characterized by a multiplication of the forms of relationality that are key to producing ethnographic insight. We pooled our observations, sharing fieldnotes, transcripts, and para-ethnographic data. We found it was interesting and also a bit nerve-wracking to share and compare our fieldnotes and journals, and to reflect together on the differences and similarities between our observations. This process was facilitated by the fact the three of us—during that summer of 2018 as well as during subsequent fieldwork in 2019—lived together in the same space. Our evenings were often filled with discussions about what we learned and planning for the next day. This hypersocial research environment helped each one of us feel a sense of ownership over our project in the making.

Graphic ethnography

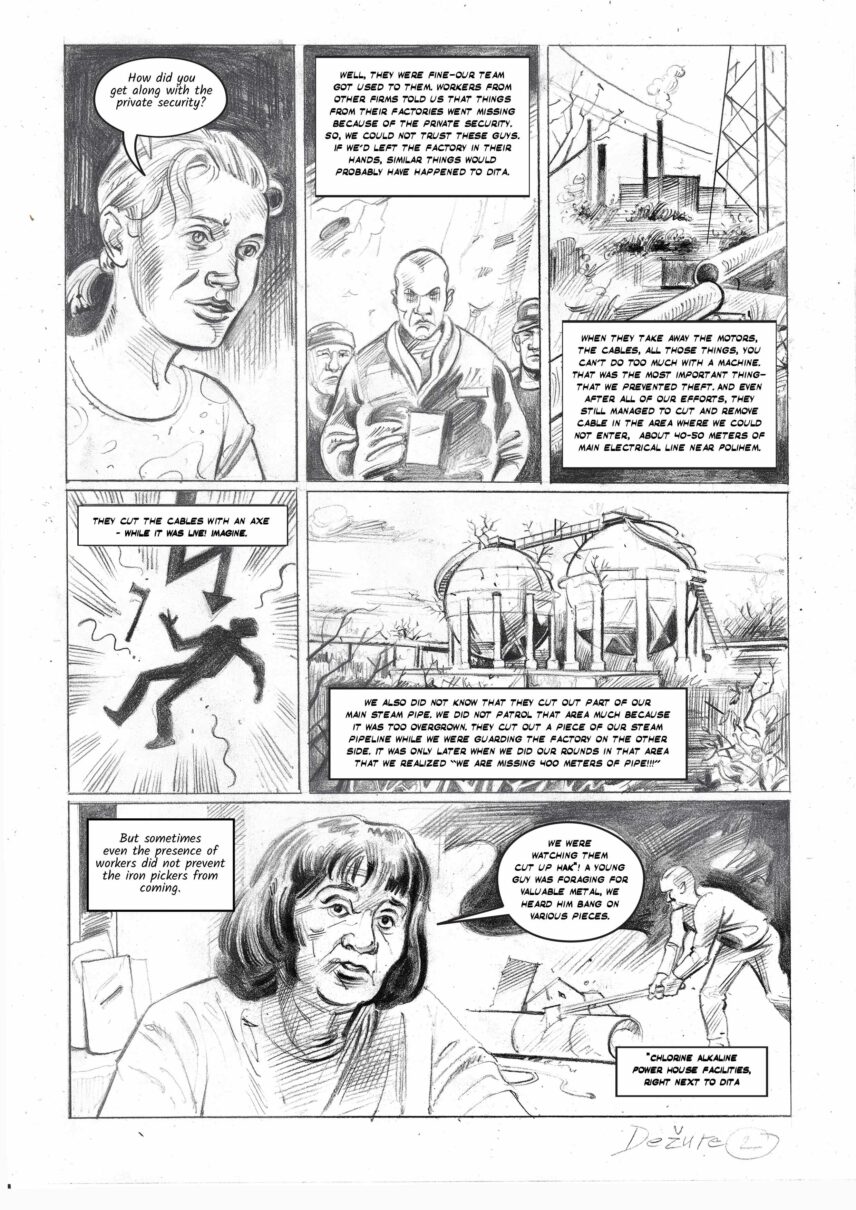

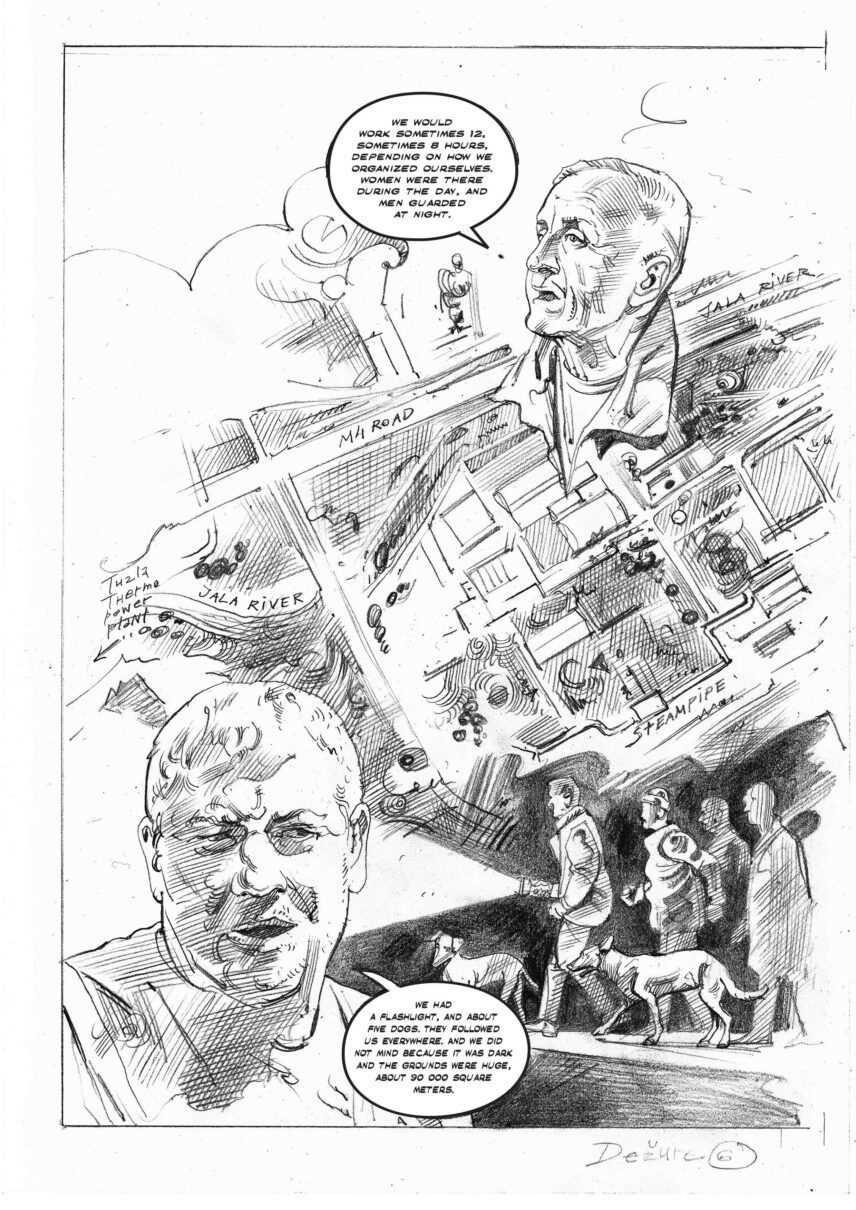

Given that the aforementioned production of sociality was crucial to the worker-lead fight for Dita, collaboratively produced graphic ethnography was ideally suited to capture the complexity of the story and its specific industrial, postsocialist setting. Our graphic book features voices of multiple actors, including the labor union leaders, workers who guarded the factory in 24-hour shifts, and various outsiders, including journalists, lawyers, professors, and student activists, who aided the workers’ cause. In bringing together an ensemble of narrators, each of whom lived the struggle in a specific manner, we can maintain the intimacy of ethnographic storytelling while also allowing our visual and textual representations to cumulatively constitute workers (and their allies) as a collective political subject, one that managed to consolidate itself in crucial moments despite its internal frictions, differences, and disagreements.

While working to establish an appropriate visual language that would capture this diversity, Boris found inspiration in the defragmented, experimental approach of some European and Argentinian comic traditions which, unlike American-style comics, are not narrowly focused on a single “hero.” Indeed, Boris plays with the “Rashomon effect,” a kind of complex understanding that emerges from the inclusion and juxtaposition of diverse, sometimes contradictory, interpretations of complicated historical events. This was particularly important because Reclaiming Dita seeks to recuperate the lived memory of the workers which often clashes with mainstream narratives about the socialist period and the postsocialist transition.

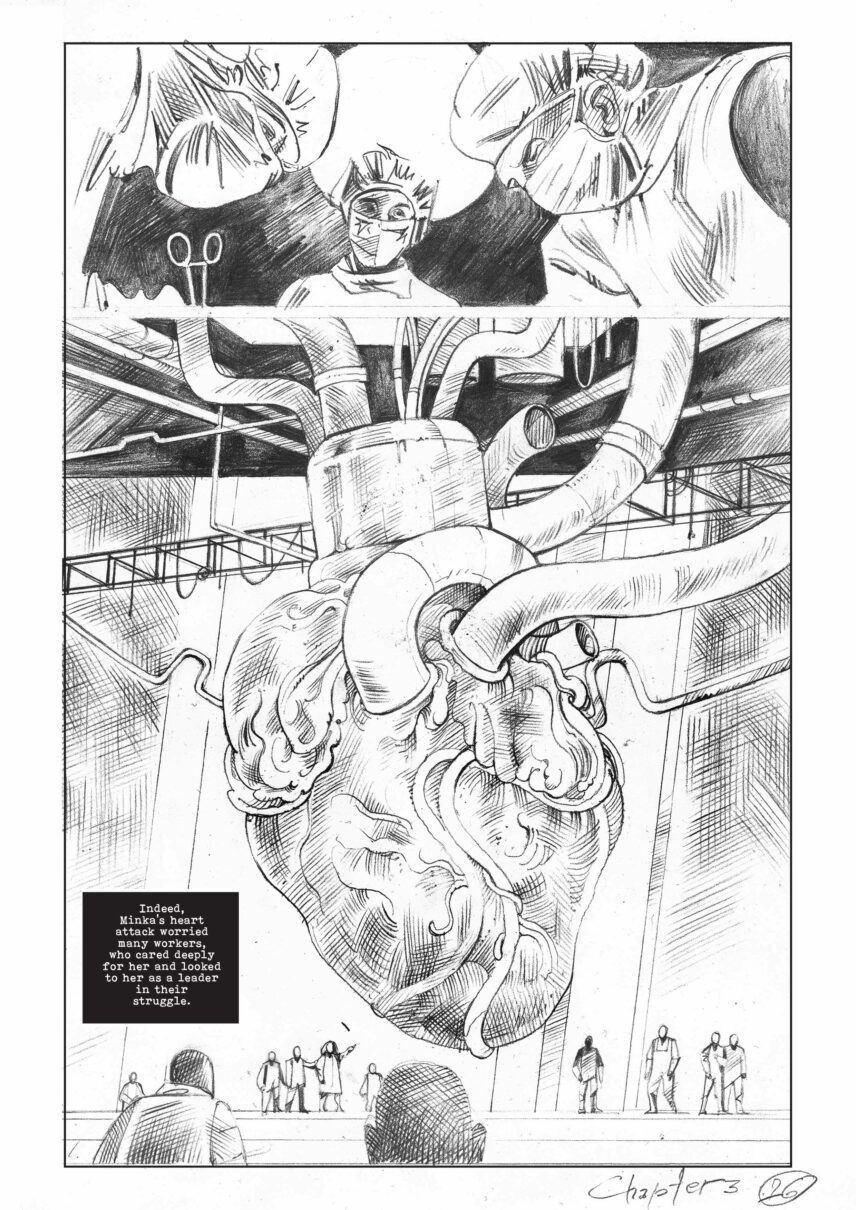

We have also found ourselves thinking visually about our research, particularly in how we relate to our interlocutors’ accounts: We pour through our coded transcripts to identify the testimonials that can be most effectively combined with graphic images to propel the narrative forward as well as elicit a powerful emotional response from readers. Boris transmutes our interlocutors’ words into graphic illustrations that vary in terms of frames and layout. At times he uses full-page spreads, usually to bring more emotional attention to certain moments and themes. At other times he opts for a row of frames to represent the synchronicity of various types of political effort involved in the mobilization.

Boris has also worked to evoke the historical context of the workers struggle by harnessing the comic medium’s capacity to bring different temporalities into relationship. By including scenes from a long history of labor-based struggle in this region, including a famous 1920 miners’ rebellion, and juxtaposing those scenes with images of the 2014 countrywide social justice protests that started in the city of Tuzla, Reclaiming Dita is able to show workers’ continuous and unbroken struggle for dignity and better life.

We have also found that black and white graphics are particularly effective in capturing the grit of industrial settings, the larger-than-life machines, and the productivist ethos of the space in which we did our research. We remain impressed by the physicality of the factory, its sounds, smells, and tastes (the sodium bicarbonate that lingers on our tongues while powder detergents are being produced)—and find the graphic format well suited for evoking this environment. Although the style of our book is realist, we are particularly excited by the more-then-realist affordances of graphic illustration. One of our favorite illustrations is the heart of Minka Busuladžić, the Dita strike leader who suffered a heart attack just prior to the 2014 protests. In Boris’s rendering the heart is plugged into the factory’s machinery, allowing us to show the centrality of Minka’s vital energy to the fight to save Dita, but also how the biological, the biopolitical, and the industrial were woven together in the lives of workers who came of age during Yugoslav socialism—a regime of production uniquely based on social, rather than private or state, ownership of means of production.

Reimagining anthropology

Our engagement with collaborative graphic ethnography in postwar Bosnia has also been inspired by the need to pursue a different kind of anthropology. The anti-privatization ethos that marked the mobilization of Dita’s workers—as well as the engaged activist research that has unfolded in Tuzla under the umbrella of Workers’ University—has played a formative role in our own experimentation with this kind of collaborative, publicly oriented anthropology that seeks to destabilize solitary fieldwork as well as individual authorship. Larisa and Andrew have long been cognizant of and uncomfortable with the inequalities that shape the terrain of knowledge production in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Due to its complex history and political realities, Bosnia emerged as a popular site of anthropological interest after the end of the 1992‒1995 Bosnian war. But much of this research has not made it back to the country in a format accessible to local audiences.

Our collaboration with local activists, academics, and workers in documenting their story—and our decision to produce a Bosnian-language version of the graphic ethnography—flows from our sensitivity to the inequalities and the extractivism that come with the ethnographic enterprise. The graphic form enables us, to use the words of anthropologist Chris Loperena (2016), to “socialize” our research findings and offer them back in a format that will be interesting to the workers as well as nonacademic audiences in Bosnia and beyond. We are excited by the possible ways that the book might advance the workers’ own political commitments. Book tour events or gallery exhibits might be a vehicle through which to animate new activist mobilizations and projects inspired by the political successes of Dita’s workers. In other words, the book might be able to produce its own political (and not just educational or scholarly) effects.

We have discovered that we must be open to practicing anthropology in new ways. Including more ethnographers (and other kinds of observers, like Boris) adds more subjects to this intersubjective process, which can lead to a thicker description or understanding as well as to new kinds of relations and with them new kinds of obligation and types of embeddedness. It requires being vulnerable and open to the desires, needs, blunders, and emotional states of others. It also means learning to inhabit the world differently in a political sense: working together—through the inevitable frictions and disagreements—and not in competition, capitalizing instead on our strengths and taking control of weaknesses. Such forms of working together are already recognized as essential to activist work, and we may well need to recognize them as also being crucial for anthropology. In other words, the decision to embrace multimodality though graphic ethnography has not only enabled us to engender new forms of representation but to produce new ways of what Ethiraj Gabriel Dattatreyan and Isaac Marrero‐Guillamón call “knowing and learning together” (2019).

This kind of collaborative research practice has had a transformational effect on our self-understanding as anthropologists and on the constitution of our desires as researchers. The political philosophers Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have proposed that activists and all others interested in provoking change ought to grab hold of the “material, social, affective, and cognitive mechanisms or apparatuses for the production of [their] subjectivity” (2011, page #). In his work as a militant researcher, our colleague Maple Razsa has described how this transformational self-production works in activist practice, an open-ended process he calls “becoming-other-than-one-is-now.” We recognize a parallel process occurring through collaborative research, what we might call “becoming-other-than-we-now-are” as ethnographers. Acknowledging that the form of our fieldwork and the representational forms that our findings take are not outside of but coexist with workers’ struggles, means that anthropology too has a part to play in envisioning and making material new kinds of political and ethical horizons.