Article begins

Teacher Education Reform as Political Theater is based on a multisited critical ethnography conducted in Russia between 2011 and 2015. The purpose of the study was to analyze teacher preparation reforms underway in Russia. I was a participant observer at two teacher education universities and one institution that became an educational policy hub in the last 20 years. I conducted 80 interviews, observed classes, participated in policy discussions, and collected various policy-related texts. Through my ethnographic engagement, I learned about a proposal for teacher education reform titled “The Concept of Teacher Education Modernization” that advocated for more practice-based teacher education, multiple routes into teaching, introduction of a licensing exam, and a modular structure of teacher education. This proposal was developed by a small group of reformers—Russian academics, most of whom were affiliated with an economics university but not with the Ministry of Education in any formal capacity. This policy and the reformers’ activities around it became the focus of my research.

What is important about this group of reformers is that they were embedded in the networks of national policy actors and experts who were developing other educational reforms—new school standards and new teacher standards. Together these reforms dramatically reoriented the Russian education system from its prior socialist commitments to equity toward market-based principles of individual choice and competition. These reformers were also embedded into global policy networks of policy edupreneurs, such as Michael Barber, and international organizations, often doing consulting or analytic work for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank. This dual positioning—along with the reformers’ general orientation towards the West—revealed itself in how teacher education reforms were conceptualized. For example, one of the reformers often used the example of England with its 27 or 28 different routes into teaching as an example to imitate in Russia. Reformers also supported the creation of “Teacher for Russia,” which emulated the “Teach for America” model that places college graduates without prior preparation for teaching in struggling schools.

When I embarked on my study, political theater was far from my mind. However, the longer I stayed in the field, the more I encountered the types of actions and interactions that drew my attention to the theatricality of what was happening. Reformers skillfully navigated a gaping divide between what they shared about the teacher education reforms publicly and what they discussed privately, whereas teacher educators targeted by these reforms described their professional lives as the theater of the absurd. Everyone seemed to be comparing their experiences to famous theater plays.

These observations drew me to the works of Erving Goffman, Bertolt Brecht, Augusto Boal, and Murray Edelman. Out of their theories, I developed a framework of political theater. On the one hand, theater elements such as lighting, scripts, masks, and props became helpful for analyzing policies and policymakers’ performances. On the other hand, this framework afforded me an opportunity to denaturalize and problematize some of the commonly held assumptions about teacher education reforms or educational policies in general. Each chapter in my book applies one or two of these elements to the policy that I analyzed.

One element of theater that I used in my analysis was selective focus—the use of light to focus the audience’s attention on a particular character and create shadows that obscure other activities on the stage. Even though the “Concept of Teacher Education Modernization” promoted changes in teacher education structures and practices, beneath the surface lay a different agenda: restrict social mobility and reorient education, so that students from different social classes would be prepared for different roles in the society.

Of course, reformers would hardly ever acknowledge this pursuit in public. Instead, they chose to shed light on the failings of public education, diverting the audience’s attention away from the bigger picture of social change. They focused their arguments on the “low quality” of teacher preparation. Even though no official data supporting their claims existed, reformers argued that teacher education is of low quality because graduates do not go to work in schools. Tweaking numbers and charts, reformers created a disparaging narrative that “only the worst” chose to become teachers. Using the results of a controversial Ministry of Education audit of higher education institutions conducted in 2012, they claimed that 75 percent of teacher education institutions were found to be “ineffective” and should be closed, along with many other higher education institutions that provided preparation in humanities, arts, or social sciences.

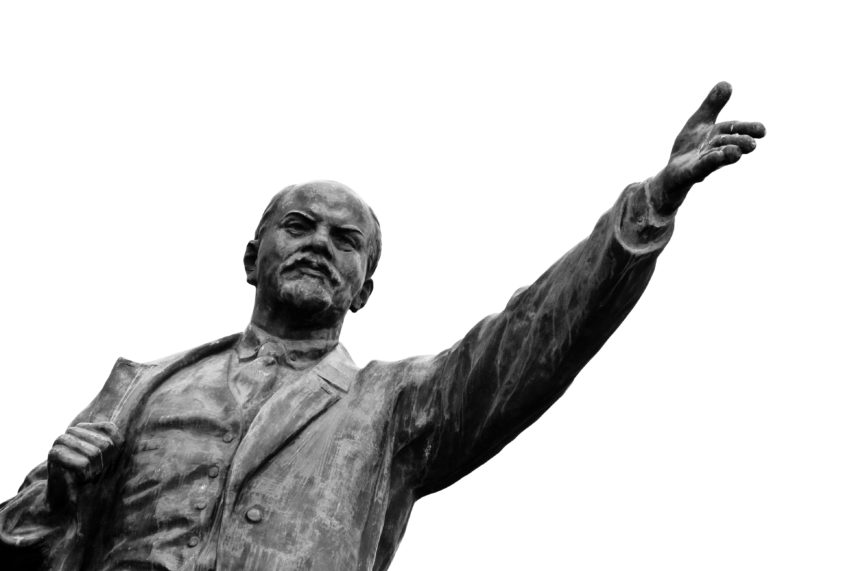

The focus on “low quality” teacher preparation obscured a major reorientation of education that reformers and other experts in their networks were pursuing through the introduction of new school standards, new teacher standards, and teacher education reforms. If the Soviet system of education focused on cultivating a “New Man” able to transform the world, then the new school standards that reformers supported focused on creating neoliberal subjectivities. “Soft skills”—or personal qualities and traits—gained prominence at the expense of other dimensions of education. As Andrei Fursenko, a former minister of education, explained in 2007, “The downside of the Soviet educational system was that it tried to create a creator. We don’t need creators, we need consumers. We need those who can consume what is produced by others.” What’s more, new school standards pursued a bifurcation in educational offerings. Most students would get access to school disciplines at the basic level, but those planning to pursue higher education would have access to advanced levels of disciplinary preparation. This bifurcation rested on reformers’ perspectives that inequality is natural and that more attention should be paid to cultivating the elites rather than wasting limited resources on those at the bottom of the social hierarchy. As one of the reformers explained, “Children in drunk parts of town don’t need advanced math, they just need socialization.” I grew up in “a drunk part of town” in the neighboring Ukraine and had to rely on the advanced math I learned in school to get to graduate school in the United States. I was genuinely distraught by this explanation.

Who stands to benefit from these reforms also remained out of sight.

The changes in Russia’s school standards and teacher standards were supposed to become the foundation for teachers’ contracts and performance-based pay. If in the past teachers were expected to cultivate multidimensional knowledge in their students, then based on the new standards their primary role became shaping students’ personalities and managing students’ behavior. Knowledge came to occupy the least important role—the point that reformers emphasized in their public engagements. These changes became the foundation for the teacher education reform where subject knowledge came to matter less but psychology and pedagogy became prominent, so that teachers could shape students’ personalities and solve students’ problems. Backstage, however, reformers discussed educational reforms as an intervention to produce the kind of subjects that would not protest against political or economic injustices. In one of the interviews for my study, a reformer brought up Maidan—the political uprising that took place in Ukraine in 2014. He spoke about how necessary educational reforms were and noted, “We don’t need another Maidan here.” Similarly, during a presentation, one of the reformers pointed out that protesters took to streets in the United States during civil rights struggles because they were not appropriately educated. The right kind of education would have prevented them from marching and demanding the recognition of their rights. Dissatisfaction with living conditions or political structures became seen as individual pathology that should be fixed through schooling. These reforms had to normalize inequality and prevent social unrest.

Who stands to benefit from these reforms also remained out of sight. By mere coincidence, during my fieldwork, I stumbled on a teaching competition for preservice teachers that was organized by one of the most prominent Russian universities. At that event, I met experts closely connected to the reformers’ networks. During a lecture, one of them spoke about teacher education reform with future teachers: “The nation needs workers. Not lawyers, managers, or humanities people. No, it simply needs qualified workers. Businesses need workers and schools don’t give them that. That’s what this reform is about.” Placing business and corporate interests at the center, these reforms worked to limit access to higher education and make sure that schools produce compliant workers.

Similar to lighting in theater, reformers’ focus on the failure of public institutions obscured how the entire system of education from K‒12 to higher education was being reoriented to create a conservative cultural change in Russia. Pursuing an elimination of vestiges of the Soviet past, reformers supported a host of policies that changed the purpose of schooling from knowledge transmission to engineering students’ personalities. Teachers’ roles also changed from enlightenment to producing more docile minds. In higher education, the focus shifted from providing broad access to limiting admissions to solidify the elite. Driven by the vision of a corporate dystopia that many in the reformers’ network pursued, these reforms became a part of modernization drama that created space-time intolerant of dissent. Yet the selective focus deployed by reformers allowed agendas of conservative social change for the sake of corporate growth to go unnoticed by educators and general public.

The framework of political theater helped me document the theatricality of Russian policymaking and describe the performative tools that Russian reformers used to hide their agendas from public scrutiny. While it can be tempting to think of fabrications, illusions, and political turns toward authoritarianism as something that happens in faraway places such as Russia, this thought is worth reconsidering. The last four years of chaotic policymaking in the United States have made it quite clear that these assumptions of difference no longer hold.

Elena Aydarova received the 2020 Council on Anthropology and Education Outstanding Book Award, for Teacher Education Reform as Political Theater: Russian Policy Drama.