Article begins

While the people of Hilljoy, MI, walk blissfully unaware next to their ghosts, we invite you to slow your stride and contemplate their meaning.

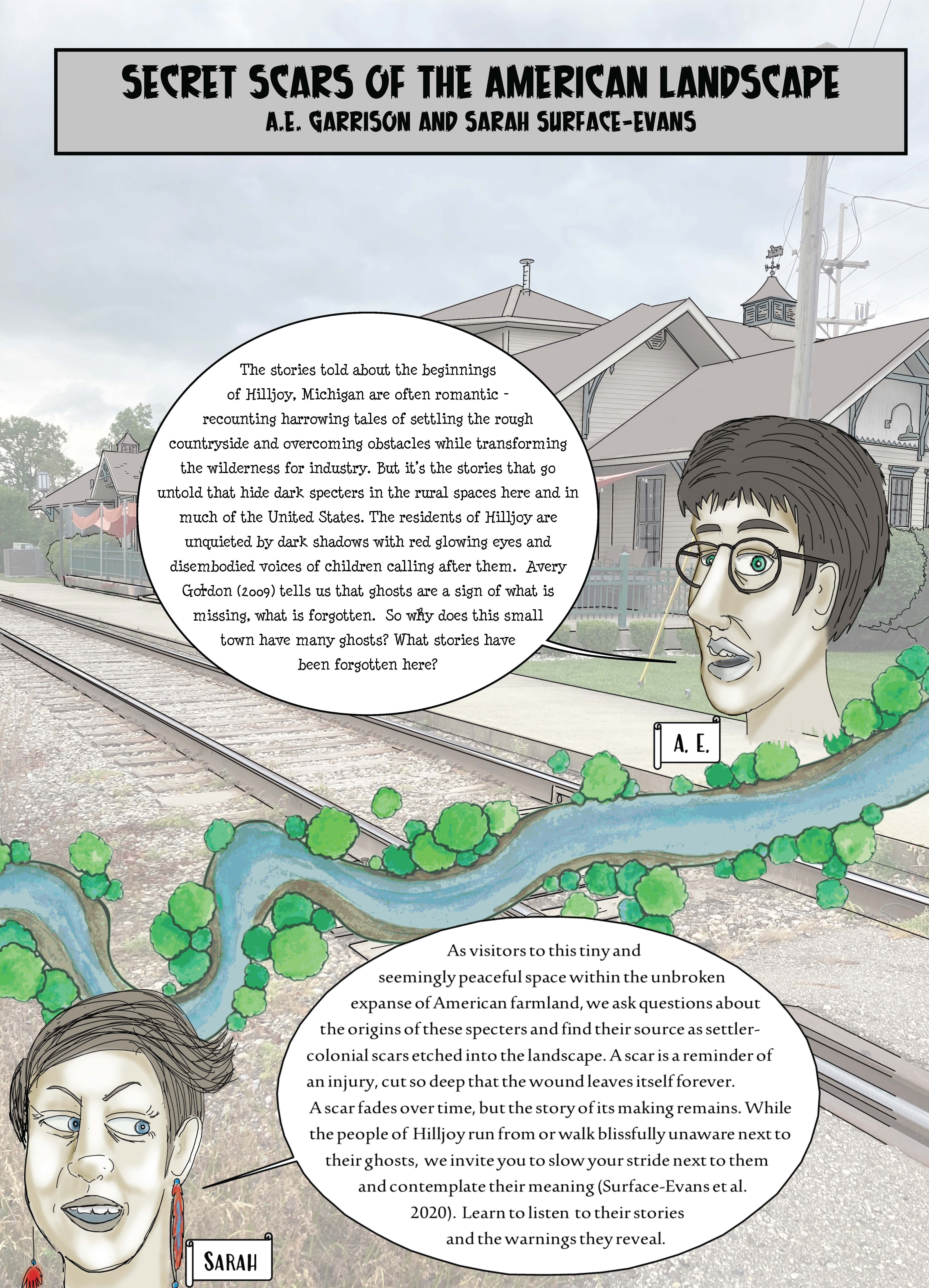

Image description: A graphic with a series of images shown over an illustration of a historic railroad station. At the top of the page is the box with the title “Secret Scares of the American Landscape” and authors, A. E. Garrison and Sarah Surface-Evans. Below the title is an illustration of A. E. with a text box that reads “The stories told about the beginnings of Hilljoy, Michigan are often romantic – recounting harrowing tales of settling the rough countryside and overcoming obstacles while transforming the wilderness for industry. But it’s the stories that go untold that hide dark specters in the rural spaces here and in much of the United States. The residents of Hilljoy are unquieted by dark shadows with red glowing eyes and disembodied voices of children calling after them. Avery Gordon (2009) tells us that ghosts are a sign of what is missing, what is forgotten. So why does this small town have so many ghosts? What stories have been forgotten here?”

Below A. E., an illustration of a flowing river as seen from above separates them from an illustration of Sarah. A speech bubble next to Sarah reads “As visitors to this tiny and seemingly peaceful space within the unbroken expanse of American farmland, we ask questions about the origins of these specters and find their source as settler-colonial scars etched into the landscape. A scar is a reminder of an injury, cut so deep that the wound leaves itself forever. A scar fades over time, but the story of its making remains. While the people of Hilljoy run from or walk blissfully unaware next to their ghosts, we invite you to slow your stride next to them and contemplate their meaning (Surface-Evans et al. 2020). Learn to listen to their stories and the warnings they reveal.”

Below A. E., an illustration of a flowing river as seen from above separates them from an illustration of Sarah. A speech bubble next to Sarah reads “As visitors to this tiny and seemingly peaceful space within the unbroken expanse of American farmland, we ask questions about the origins of these specters and find their source as settler-colonial scars etched into the landscape. A scar is a reminder of an injury, cut so deep that the wound leaves itself forever. A scar fades over time, but the story of its making remains. While the people of Hilljoy run from or walk blissfully unaware next to their ghosts, we invite you to slow your stride next to them and contemplate their meaning (Surface-Evans et al. 2020). Learn to listen to their stories and the warnings they reveal.”

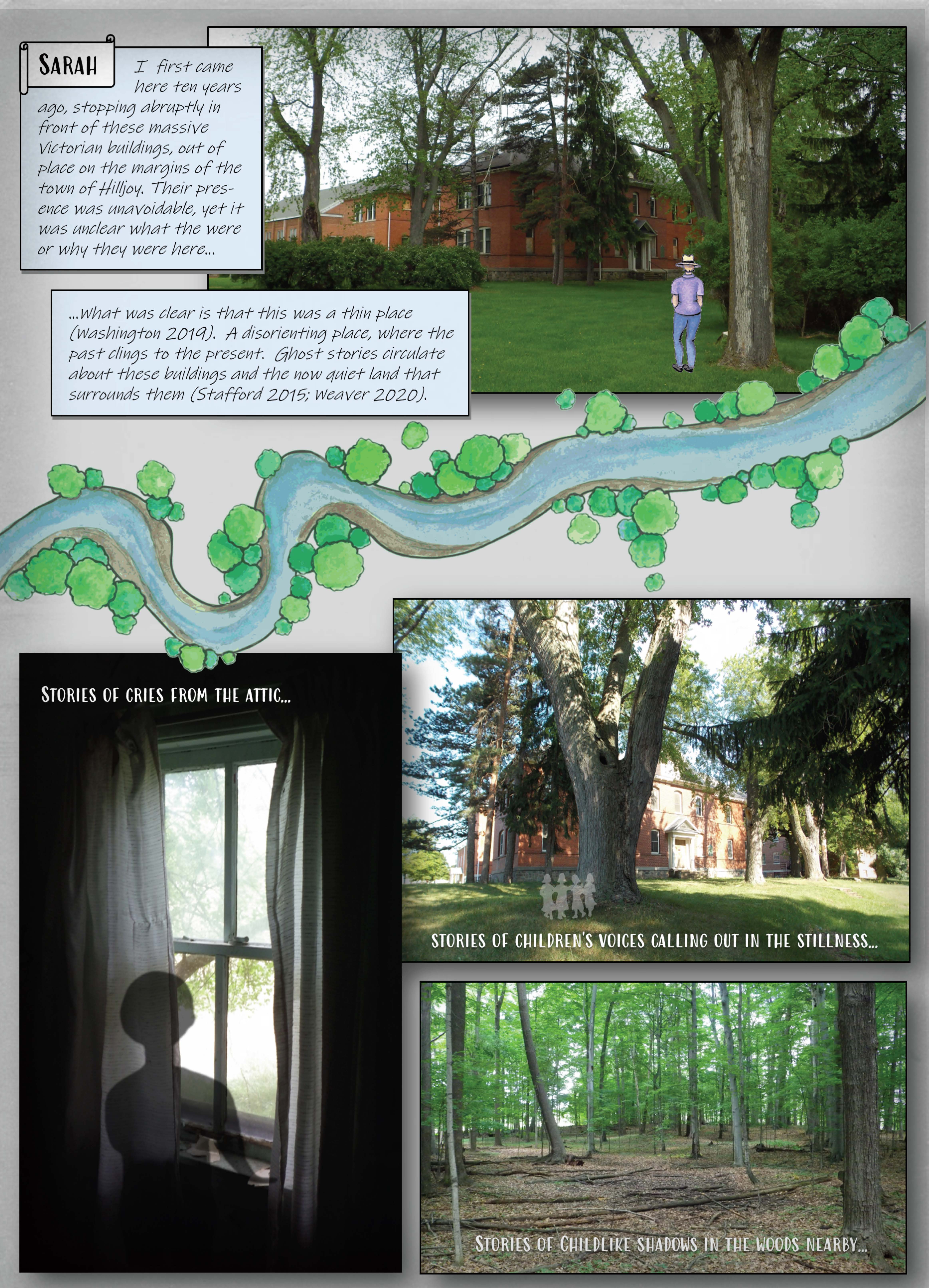

Image description: A series of images that comprise four panels narrated by Sarah and an external narrator. Sarah tells the story of Hilljoy from the perspective of a visible wound on the landscape. The first panel is Sarahs voice and reads: “I first came here ten years ago, stopping abruptly in front of these massive Victorian buildings, out of place on the margins of the town of Hilljoy. Their presence was unavoidable, yet it was unclear what the were or why they were here…What was clear is that this was a thin place (Washington 2019). A disorienting place, where the past clings to the present. Ghost stories circulate about these buildings and the now quiet land that surrounds them (Stafford 2015; Weaver 2020).” This text is next to a photograph of an institutional brick building surrounded by old trees and green lawn. An illustration of Sarah standing next to one of the trees and facing the building was added to the photograph.

Below the first panel is the same river from page 1. It flows and meanders across the page. Next are three panels with graphically embellished photographs and text from the external narrator. The first is a photograph of a dark room, looking out of a window. A slightly transparent silhouette of a child stands in front of the window. The text on this image reads: “Stories of cries from the attic…”

The next panel is a photograph of more intuitional buildings surrounded by large trees. In the shadows near the trees is a group of ghostly children playing. The text on this image reads: “Stories of children’s voices calling out in the stillness…”

The last panel on the page is a photograph of an old-growth forest. Slightly transparent silhouettes of children peak from behind several of the trees. The text on this image reads: “Stories of Childlike shadows in the woods nearby…”

Below the first panel is the same river from page 1. It flows and meanders across the page. Next are three panels with graphically embellished photographs and text from the external narrator. The first is a photograph of a dark room, looking out of a window. A slightly transparent silhouette of a child stands in front of the window. The text on this image reads: “Stories of cries from the attic…”

The next panel is a photograph of more intuitional buildings surrounded by large trees. In the shadows near the trees is a group of ghostly children playing. The text on this image reads: “Stories of children’s voices calling out in the stillness…”

The last panel on the page is a photograph of an old-growth forest. Slightly transparent silhouettes of children peak from behind several of the trees. The text on this image reads: “Stories of Childlike shadows in the woods nearby…”

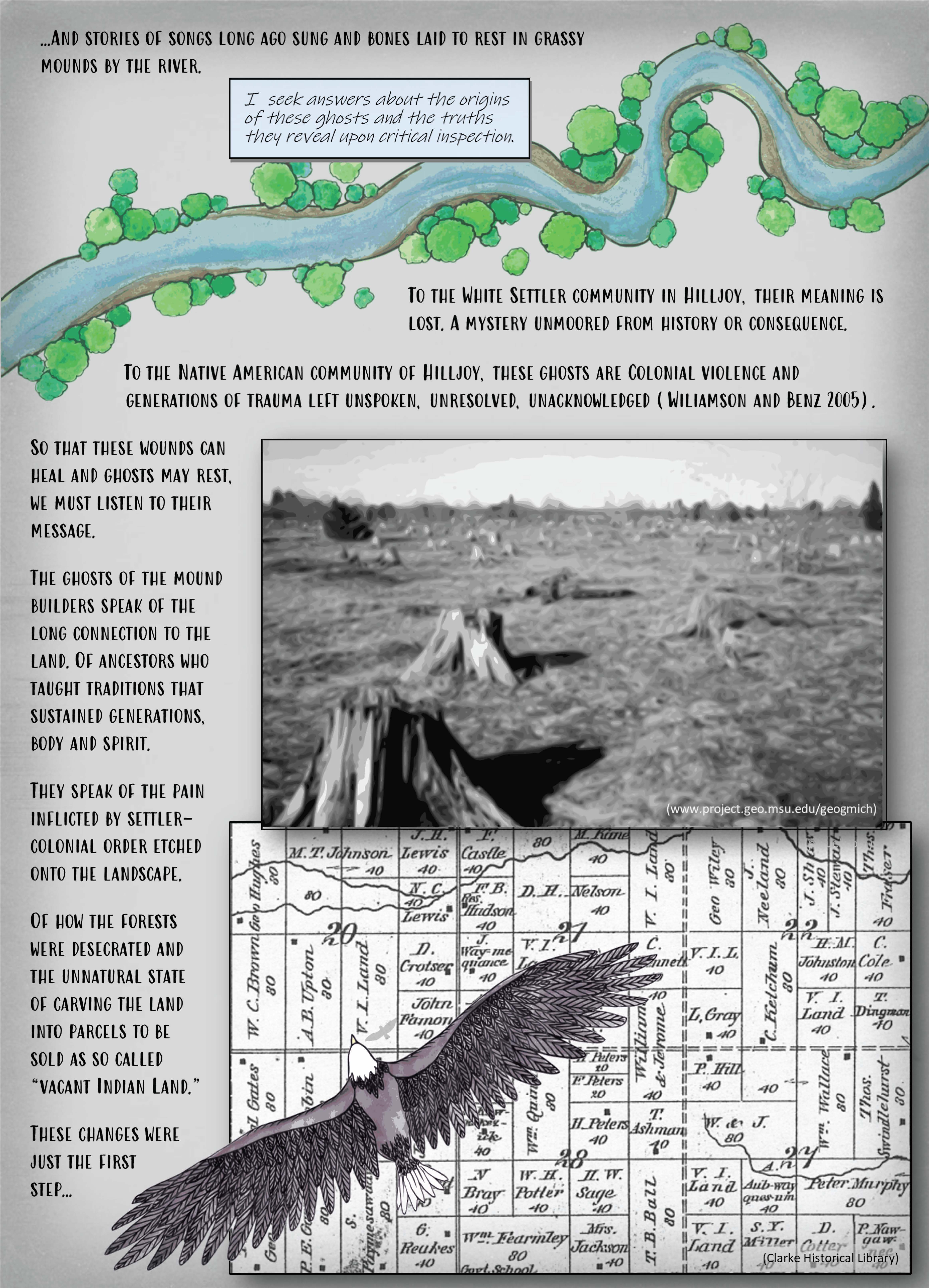

Image description: Sarah’s story continues onto page 3. At the top of the page, is the illustration of the river. Nearby, text from the external narrator reads: “…And stories of songs long ago sung and bones laid to rest in grassy mounds by the river.”

Next to this is a box indicating Sarah’s voice states: “I seek answers about the origins of these ghosts and the truths they reveal upon critical inspection.”

Below the river are two images. The first is a black and white scene of a landscape ravaged by nineteenth-century logging, known as the Kingston Plains (Image credit MSU Geography). The second image is a close-up of a historic 1879 Plat Map of Isabella Township in Isabella County, Michigan (Image credit Clarke Historical Library). Overlaid on the map is an illustration of a bald eagle (migizi in Anishnaabemowin) flying over the map landscape. The eagle’s beak points to a parcel labeled “V. I. Land” on the Plat Map, which stands for “vacant Indian land.”

Surrounding these images is text from the external narrator, “To the White Settler community in Hilljoy, their meaning is lost. A mystery unmoored from history or consequence. To the Native American community of Hilljoy, these ghosts are Colonial violence and generations of trauma left unspoken, unresolved, unacknowledged (Wiliamson and Benz 2005). So that these wounds can heal and ghosts may rest, we must listen to their message. The ghosts of the mound builders speak of the long connection to the land. Of ancestors who taught traditions that sustained generations, body and spirit. They speak of the pain inflicted by settler-colonial order etched onto the landscape. Of how the forests were desecrated and the unnatural state of carving the land into parcels to be sold as so-called ‘vacant Indian land.’ These changes were just the first step…”

Next to this is a box indicating Sarah’s voice states: “I seek answers about the origins of these ghosts and the truths they reveal upon critical inspection.”

Below the river are two images. The first is a black and white scene of a landscape ravaged by nineteenth-century logging, known as the Kingston Plains (Image credit MSU Geography). The second image is a close-up of a historic 1879 Plat Map of Isabella Township in Isabella County, Michigan (Image credit Clarke Historical Library). Overlaid on the map is an illustration of a bald eagle (migizi in Anishnaabemowin) flying over the map landscape. The eagle’s beak points to a parcel labeled “V. I. Land” on the Plat Map, which stands for “vacant Indian land.”

Surrounding these images is text from the external narrator, “To the White Settler community in Hilljoy, their meaning is lost. A mystery unmoored from history or consequence. To the Native American community of Hilljoy, these ghosts are Colonial violence and generations of trauma left unspoken, unresolved, unacknowledged (Wiliamson and Benz 2005). So that these wounds can heal and ghosts may rest, we must listen to their message. The ghosts of the mound builders speak of the long connection to the land. Of ancestors who taught traditions that sustained generations, body and spirit. They speak of the pain inflicted by settler-colonial order etched onto the landscape. Of how the forests were desecrated and the unnatural state of carving the land into parcels to be sold as so-called ‘vacant Indian land.’ These changes were just the first step…”

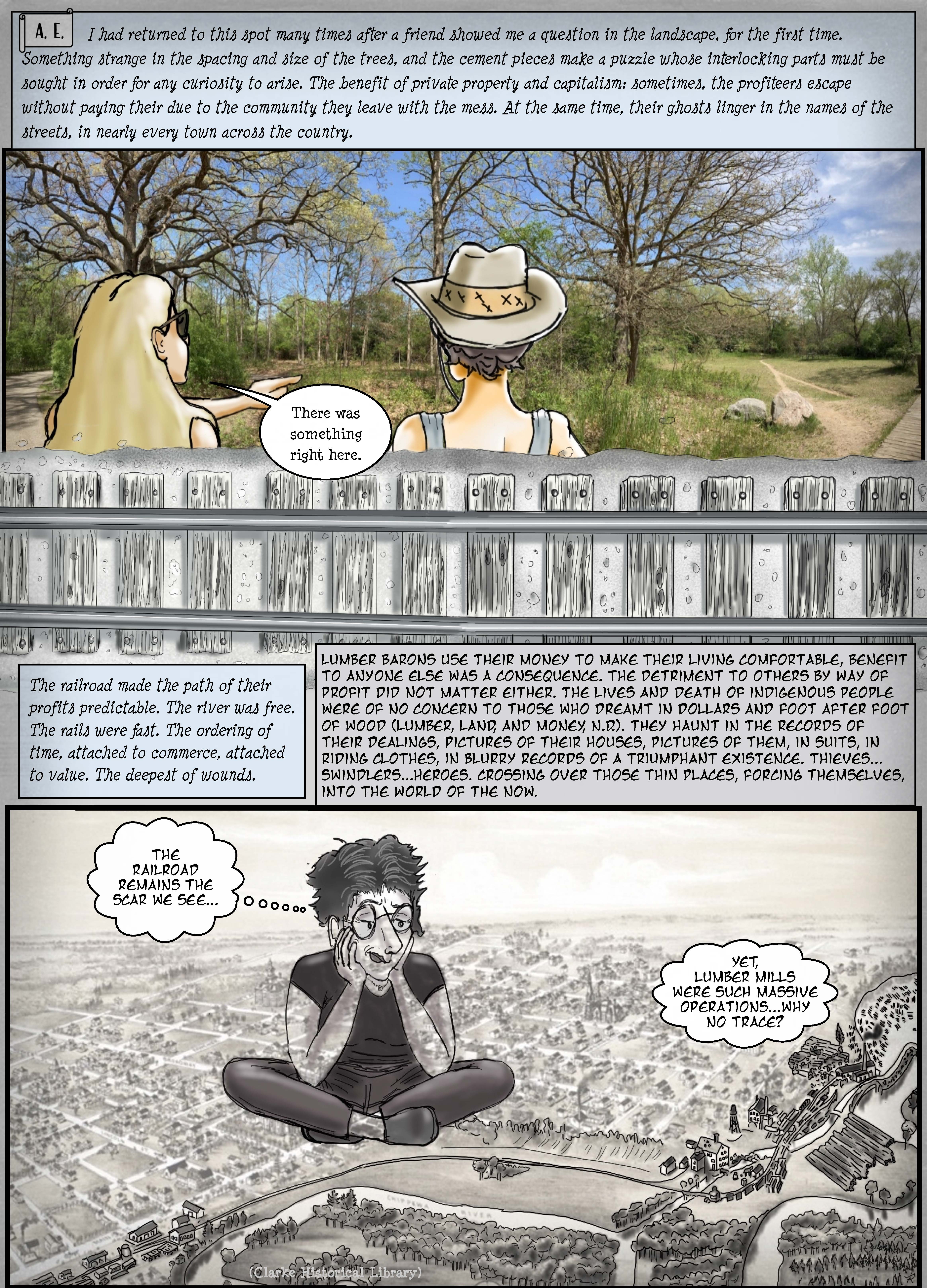

Image description: Narration from A. E. picks up on page 4, which is composed of several panels of images. A. E. shares the story of Hilljoy from the perspective of the hidden wounds of the lumber industry. The frame at the top of the page is a photograph of a trailside grove of giant trees. Two illustrated people stand with their backs to the audience, looking at the grove of trees. The person on the left is pointing, saying, “There was something right here.” The other person is A. E. and stands to the right. According to the historic map covering the illustration at the bottom of the page, this grove of old trees might have seen a lumber operation here on this bluff of the Mill Pond. Below this frame, an illustration of A. E. sits on top of the Birds-eye map of the city of Mount Pleasant in 1884 (courtesy of the Clarke Library, Central Michigan University), cross-legged and perplexed over the presence of the lumber mill that had left no trace. “How could such a huge operation simply disappear?” wonders A. E.

An illustration of railroad track from a birds-eye view runs through the center of the page. A text box near the railroad indicating A. E.’s voice reads. “The railroad made the path of their profits predictable. The river was free. The rails were fast. The ordering of time, attached to commerce, attached to value. The deepest of wounds.” The external narrator tells us “Lumber barons use their money to make their living comfortable, benefit to anyone else was a consequence. The detriment to others by way of profit did not matter either. The lives and death of indigenous people were of no concern to those who dreamt in dollars and foot after foot of wood (Lumber, Land, and money, n.d.). They haunt in the records of their dealings, pictures of their houses, pictures of them, in suits, in riding clothes, in blurry records of a triumphant existence. Thieves… swindlers…heroes. Crossing over those thin places, forcing themselves, into the world of the now.”

An illustration of railroad track from a birds-eye view runs through the center of the page. A text box near the railroad indicating A. E.’s voice reads. “The railroad made the path of their profits predictable. The river was free. The rails were fast. The ordering of time, attached to commerce, attached to value. The deepest of wounds.” The external narrator tells us “Lumber barons use their money to make their living comfortable, benefit to anyone else was a consequence. The detriment to others by way of profit did not matter either. The lives and death of indigenous people were of no concern to those who dreamt in dollars and foot after foot of wood (Lumber, Land, and money, n.d.). They haunt in the records of their dealings, pictures of their houses, pictures of them, in suits, in riding clothes, in blurry records of a triumphant existence. Thieves… swindlers…heroes. Crossing over those thin places, forcing themselves, into the world of the now.”

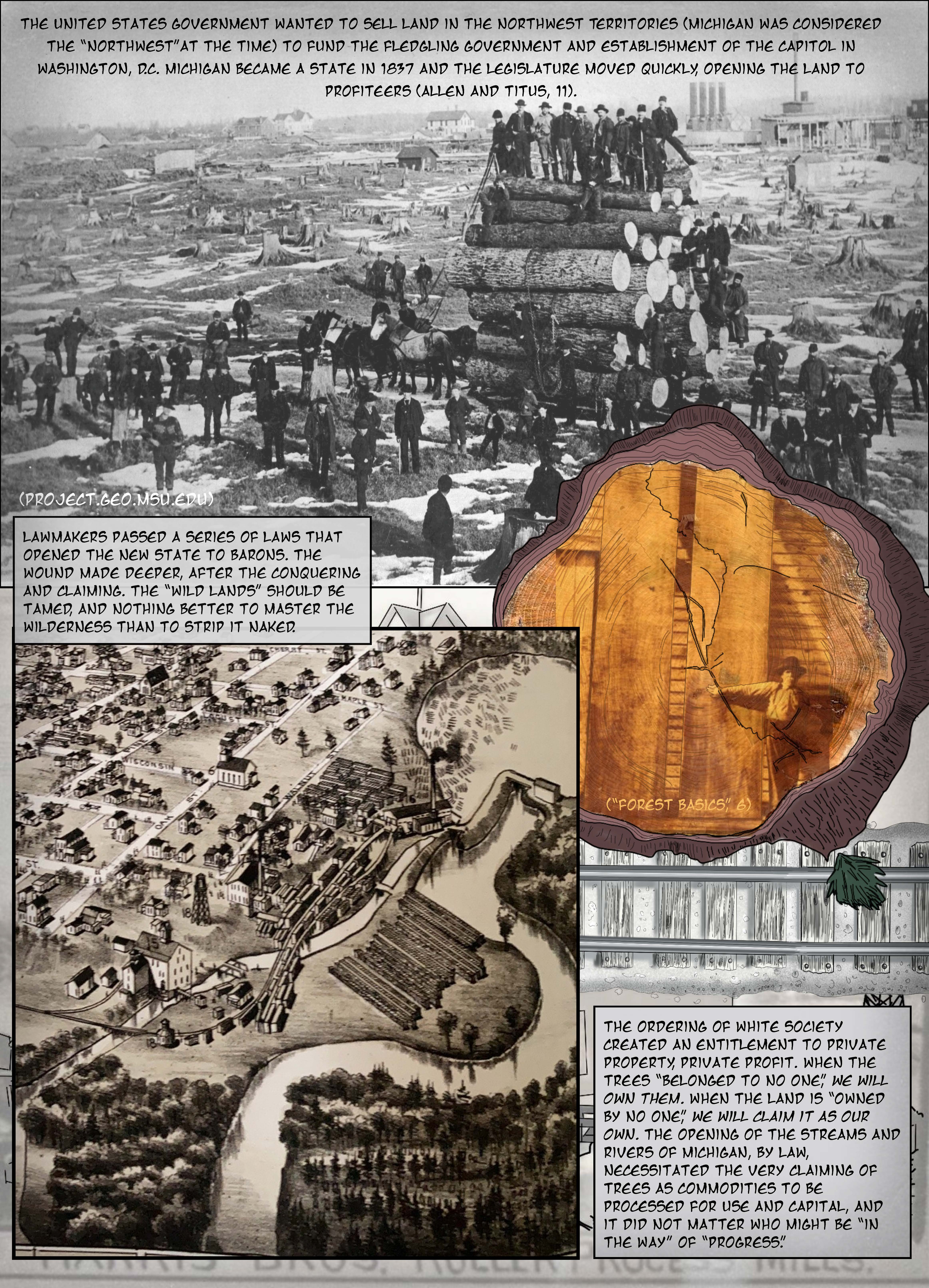

Image description: A. E.’s story continues on page 5. At the top of the page is a historic photograph from the Michigan State University archives, capturing the extent of the lumber industry in Michigan. A black and white photograph shows giant trees atop a sled, topped with a number of men in hats and coats. This photograph was taken some time in the flush of the 1800s lumber boom in the state, at a lumber operation in the Upper Peninsula. The external narrator tells us that “The United States government wanted to sell land in the Northwest Territories (Michigan was considered the ‘Northwest’ at the time) to fund the fledgling government and establishment of the capitol in Washington, D.C. Michigan became a state in 1837 and the legislature moved quickly, opening the land to profiteers (Allen and Titus, 11). Lawmakers passed a series of laws that opened the new state to barons. The wound made deeper, after the conquering and claiming. The ‘wild lands’ should be tamed, and nothing better to master the wilderness than to strip it naked.”

Below the historic photograph is a series of illustrations meant to conjure the nostalgia, not the memory, of the logging boom. One is a close-up of the lumber mill from a birds-eye view. Another image is an overlay of a tree stump, with growth rings showing, superimposed with a historic image of a man dressed in nineteenth-century clothing and pointing to an impressively large cut board from a single tree. Under these images, the railroad tracks continue across the page. Slicing the landscape. The external narrator states, “The ordering of White society created an entitlement to private property, private profit. When the trees ‘belonged to no one,’ We will own them. When the land is ‘owned by no one,’ We will claim it as our own. The opening of the streams and rivers of Michigan, by law, necessitated the very claiming of trees as commodities to be processed for use and capital, and it did not matter who might be ‘in the way’ of ‘progress’.”

Below the historic photograph is a series of illustrations meant to conjure the nostalgia, not the memory, of the logging boom. One is a close-up of the lumber mill from a birds-eye view. Another image is an overlay of a tree stump, with growth rings showing, superimposed with a historic image of a man dressed in nineteenth-century clothing and pointing to an impressively large cut board from a single tree. Under these images, the railroad tracks continue across the page. Slicing the landscape. The external narrator states, “The ordering of White society created an entitlement to private property, private profit. When the trees ‘belonged to no one,’ We will own them. When the land is ‘owned by no one,’ We will claim it as our own. The opening of the streams and rivers of Michigan, by law, necessitated the very claiming of trees as commodities to be processed for use and capital, and it did not matter who might be ‘in the way’ of ‘progress’.”

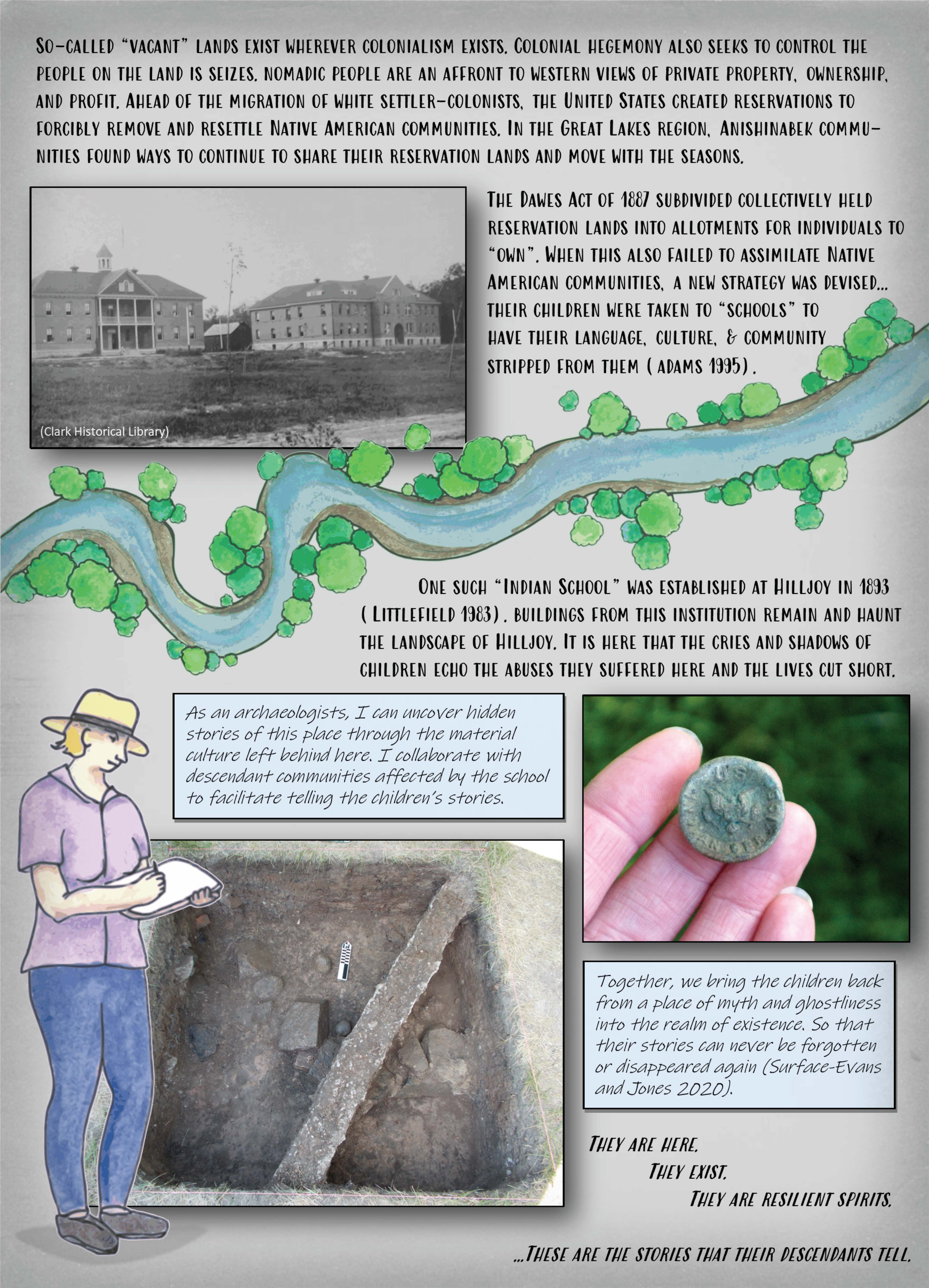

Image description: We return to Sarah’s portion of the story. A series of images cover the page with text woven around them. Near the top of the page, is a historic image of the same institutional buildings from page 2. The black and white image shows two large brick buildings with imposing Federal style architecture. The grounds surrounding the buildings look sparse, but a forested area can be seen in the background behind the buildings. The text surrounding this image reads: “So-called ‘vacant’ lands exist wherever colonialism exists. Colonial hegemony also seeks to control the people on the land is seizes. nomadic people are an affront to western views of private property, ownership, and profit. Ahead of the migration of white settler-colonists, the United States created reservations to forcibly remove and resettle Native American communities. In the Great Lakes region, Anishinabek communities found ways to continue to share their reservation lands and move with the seasons. The Dawes Act of 1887 subdivided collectively held reservation lands into allotments for individuals to “own”. When this also failed to assimilate Native American communities, a new strategy was devised… their children were taken to ’schools’ to have their language, culture, & community stripped from them (Adams 1995). One such ‘Indian School’ was established at Hilljoy in 1893 (Littlefield 1983). buildings from this institution remain and haunt the landscape of Hilljoy. It is here that the cries and shadows of children echo the abuses they suffered here and the lives cut short.”

The winding illustration of the river flows beneath this image and text. Below are several images and text boxes with Sarah’s narration. On the left side of the page is an illustration of Sarah wearing outdoor clothes for archaeological fieldwork and writing on a clipboard. A textbox nearby reads: “As an archaeologist, I can uncover the hidden stories of this place through the material culture left behind here. I collaborate with descendant communities affected by the school to facilitate telling the children’s stories.” Below this is a photograph of an excavation unit in progress, showing a concrete and cobblestone foundation of a demolished building exposed in the soil and surrounded by artifacts. A second photograph is a close-up of Sarah’s hand holding a copper US Indian Service Button, recovered from the site. A text box indicating Sarah’s voice reads “Together, we bring the children back from a place of myth and ghostliness into the realm of existence. So that their stories can never be forgotten or disappeared again (Surface-Evans and Jones 2020).”

At the bottom right corner of the page, the external narrator states: “They are here. They exist. They are resilient spirits…These are the stories that their descendants tell.”

The winding illustration of the river flows beneath this image and text. Below are several images and text boxes with Sarah’s narration. On the left side of the page is an illustration of Sarah wearing outdoor clothes for archaeological fieldwork and writing on a clipboard. A textbox nearby reads: “As an archaeologist, I can uncover the hidden stories of this place through the material culture left behind here. I collaborate with descendant communities affected by the school to facilitate telling the children’s stories.” Below this is a photograph of an excavation unit in progress, showing a concrete and cobblestone foundation of a demolished building exposed in the soil and surrounded by artifacts. A second photograph is a close-up of Sarah’s hand holding a copper US Indian Service Button, recovered from the site. A text box indicating Sarah’s voice reads “Together, we bring the children back from a place of myth and ghostliness into the realm of existence. So that their stories can never be forgotten or disappeared again (Surface-Evans and Jones 2020).”

At the bottom right corner of the page, the external narrator states: “They are here. They exist. They are resilient spirits…These are the stories that their descendants tell.”

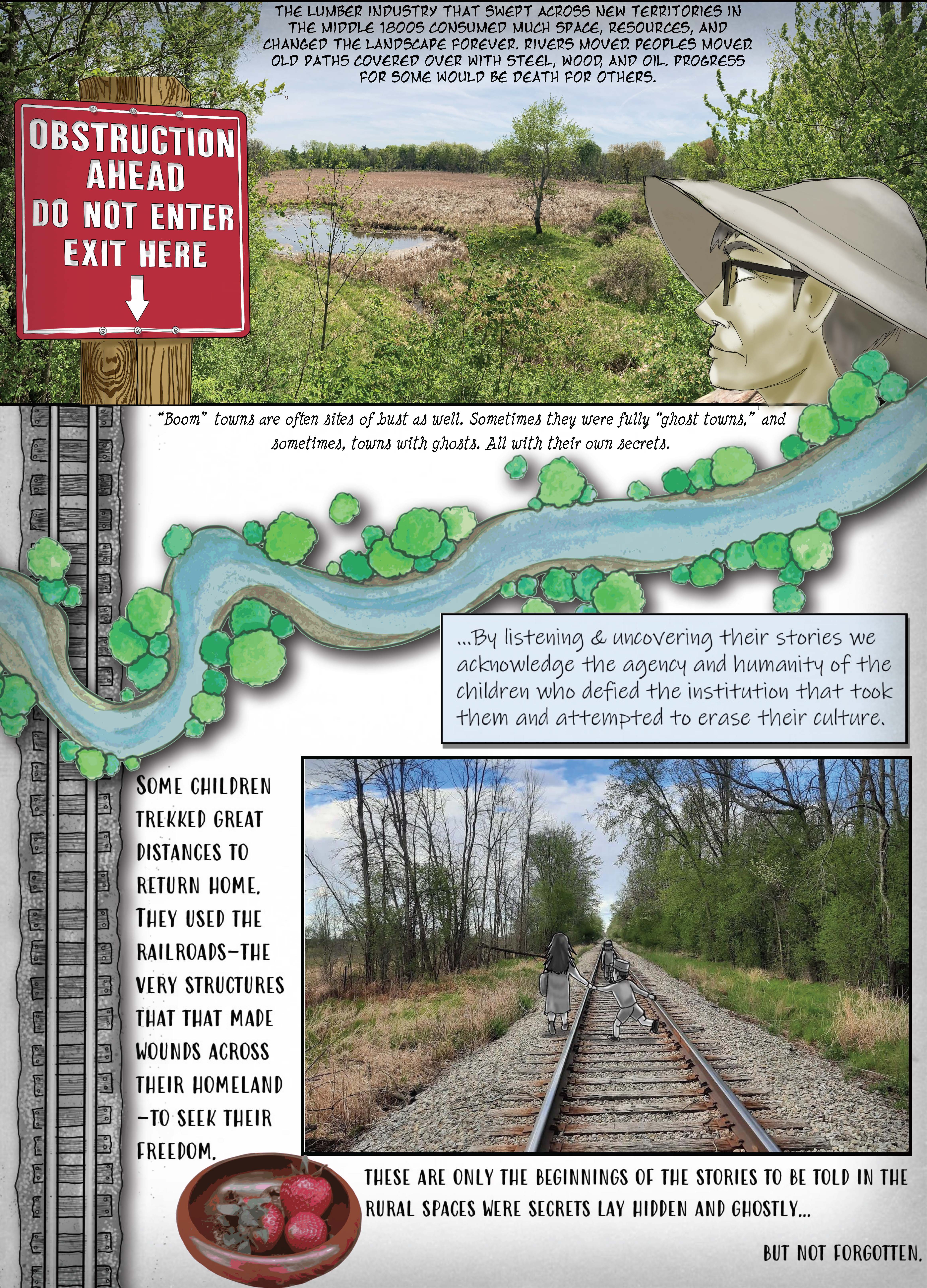

Image description: At the top of the page, a photograph of Hilljoy’s “mill pond,” now a marshy refuge for birds and otherwise, from the observation deck provided by the city of its city park system. The overlook is on the same part of the path and in the same part of the park as the grove of trees (pg 4). A. E.’s character looks out over the marsh. On the left side of the photo is a photo-reference of the “Warning” sign that sits at a fork of the Chippewa River where the mill pond begins. The external narrator tells us, “The lumber industry that swept across new territories in the middle 1800s consumed much space, resources, and changed the landscape forever. Rivers moved. Peoples moved. Old paths covered over with steel, wood, and oil. Progress for some would be death for others”

Parks are often the best use of land that was once used for industry and might be too heavily contaminated (even a century later) to use for residential zoning or otherwise. These properties would also be a bargain for a small, low-revenue-flow city, like Hilljoy; the price per parcel reduced to entice the buyer and relieve the seller. Toxic waste and residue included. A text box indicating A. E.’s voice reads, “Boom” towns are often sites of bust as well. Sometimes they were fully “ghost towns,” and sometimes, towns with ghosts. All with their own secrets”

Below the image with A. E. an illustration of a railroad track runs along the left side of the page, intersecting the illustration of the winding river. We return to Sarah’s story and in a textbox, they explain: “…By listening & uncovering their stories we acknowledge the agency and humanity of the children who defied the institution that took them and attempted to erase their culture.” Below this is a photograph of the railroad tracks, illustrated over this image are two children, a girl that looks about 12-10 years old and a boy that looks about 5-7 years old, dressed in gray uniforms walking away from the viewer. Next to this photograph, text from the narrator reads: “Some children trekked great distances to return home. They used the railroads—the very structures that made wounds across their homeland-to seek their freedom.”

Below this is an illustration of a bowl of strawberries (ode’iminan in Anishnaabemowin). Next to this offering of strawberries, the external narrator leaves us with concluding thoughts: “these are only the beginnings of the stories to be told in the rural spaces were secrets lay hidden and ghostly…but not forgotten.”

Parks are often the best use of land that was once used for industry and might be too heavily contaminated (even a century later) to use for residential zoning or otherwise. These properties would also be a bargain for a small, low-revenue-flow city, like Hilljoy; the price per parcel reduced to entice the buyer and relieve the seller. Toxic waste and residue included. A text box indicating A. E.’s voice reads, “Boom” towns are often sites of bust as well. Sometimes they were fully “ghost towns,” and sometimes, towns with ghosts. All with their own secrets”

Below the image with A. E. an illustration of a railroad track runs along the left side of the page, intersecting the illustration of the winding river. We return to Sarah’s story and in a textbox, they explain: “…By listening & uncovering their stories we acknowledge the agency and humanity of the children who defied the institution that took them and attempted to erase their culture.” Below this is a photograph of the railroad tracks, illustrated over this image are two children, a girl that looks about 12-10 years old and a boy that looks about 5-7 years old, dressed in gray uniforms walking away from the viewer. Next to this photograph, text from the narrator reads: “Some children trekked great distances to return home. They used the railroads—the very structures that made wounds across their homeland-to seek their freedom.”

Below this is an illustration of a bowl of strawberries (ode’iminan in Anishnaabemowin). Next to this offering of strawberries, the external narrator leaves us with concluding thoughts: “these are only the beginnings of the stories to be told in the rural spaces were secrets lay hidden and ghostly…but not forgotten.”