Article begins

This column is based on Andrea Flores’s book, The Succeeders: How Immigrant Youth are Transforming What it Means to Belong in America. The Succeeders won the 2022 Council on Anthropology and Education Outstanding Book Award. Find out more about the annual CAE book award and the nomination process on the CAE website.

The former student I called “Isabel” zooms into my seminar to talk about her journey from high schooler frustrated by the barriers she faced as an undocumented student to her career as a community organizer. I have been a witness to this trajectory, watching her navigate the end of high school, her entry into higher education, and her first few jobs. My students are deeply engaged as she confidently relates her professional history and ways both to get involved in the immigrant rights movement and to care for undocumented students on campus.

Isabel is one of the eponymous “Succeeders”—youths who participated in a college access program for Latinx youth in Nashville, Tennessee, where I conducted fieldwork in 2012–2013. I undertook this project attempting to understand how young people like Isabel conceptualized the value of their educations. I was also interested in how these youths made it to college in a city that had struggled to accept immigrant families just as these young people entered school. For the Succeeders, becoming educated was about accessing a sense of national belonging amidst the nativist racism that continues to plague the contemporary United States and supposed “New South.” It was also about remaking belonging’s limited terms through acts of care that make family both at home and with each other.

The Succeeders were an eclectic group. Some were high achievers in failing schools. Others were struggling to graduate. Many more were in the unassuming middle, failing to gain their educators’ attention as either standouts or potential dropouts. Representative of the demographic profile of the local Latinx community, most students were Mexican or Central American in familial origin and around half were undocumented, with many having mixed status families. Once together in the afterschool college access program, these youths discovered they had much in common—like shared experiences of caring for younger siblings or finding out that as an undocumented person going to college would be tricky, but not impossible. As these students became friends across levels of academic achievement, citizen status, and other divisive labels, they created a supportive space where they could explore their identities as Latinx, immigrant/immigrant-origin youths and share their struggles as teenagers. Additionally, they could critique both their schools and nation that seemed to disregard Succeeders’ worth as community members.

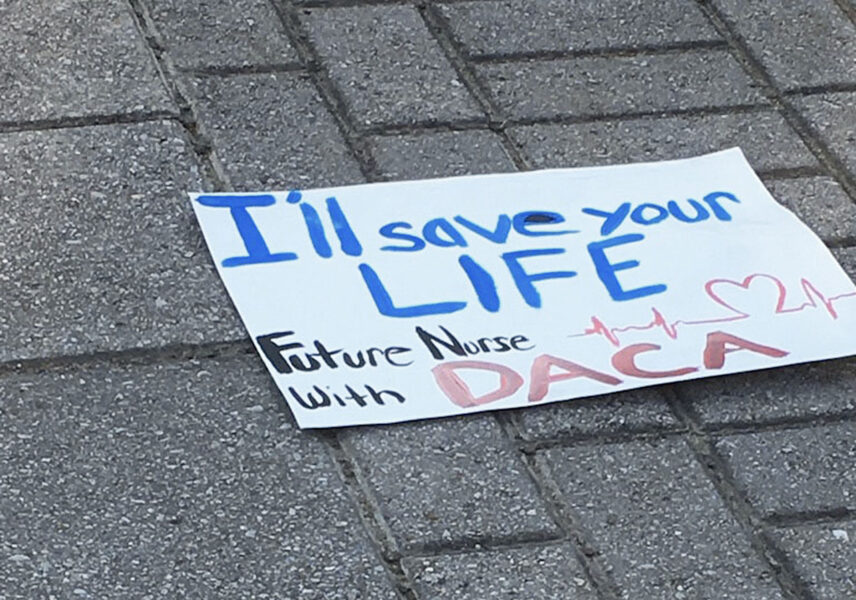

The linkage of these latter two categories—schools and the nation—is integral to my book’s arguments. As Thea Abu El-Haj argues, the public school is where immigrant and immigrant-descendant youth “encounter normative discourses of citizenship and belonging” and are “invited to become citizens” or not. Moreover, for undocumented youth, schools can be a haven of inclusion that counters or at least delays the exclusion that undocumented adults face. For the Succeeders, these normative discourses and access to havens of inclusion centered around being academically successful. Academic success, in the age of the Dream Act and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, has taken on political and moral significance as “Dreamers” like the Succeeders are marked in policy as deserving migrants who should not be blamed for their parents’ criminalized migration. Yet academic success, and success in the national meritocracy more broadly, has long been the sociopolitical prerequisite for minoritized and immigrant individuals’ right to belong.

Succeeders saw their educations as a way to counter the racialized and moralized stereotypes they encountered about Latinx people—stereotypes that seemed to prohibit Latinx people from being included in and valued by the nation and its members. Alejandro linked his educational aspirations and stereotypes very directly: “I want to change the stereotype[…]If people see that Hispanics are trying to better themselves by going to college, then possibly it will end the stereotypes[…]they’re not going to get pregnant when they’re in high school. We are smart. We are not going to[…]mow your lawn.” Alejandro clearly links educational success with stigmatized Latinx fertility and manual labor racialized as Latinx.

College admissions became a central and highly stressful proving ground for Alejandro and others to disprove stereotypes and prove their worth to themselves and others. Lupita described applying to one college as a way to prove to her racist employer, whose son was an alumnus from that same school, that “I’m just as good as you are.” Moreover, aspects of the admissions process, such as the dreaded college admissions essay, primed students to reproduce certain narratives of the Latinx self. Students believed that admissions officers expected what students termed the “being Hispanic essay” which they described as “some sad story” about how Succeeders were the “good” kind of Latinx immigrant person who faced adversity, adhered to the value of hard work, sought self-improvement, and achieved academically.

Lupita described having “at least 10 essays that say ‘I’m Hispanic’” as part of her admissions packet. In these essays, Lupita did not just mark herself as another deserving college applicant and “good” Latinx person, but reproduced the narratives of national exclusion for other Latinx youth. She wrote about her ethno-racial difference, but also that “I understood what it was like to be an American, and that I’m not the typical Hispanic.” What she meant by the “typical Hispanic,” she explained, was precisely the same stereotypes—and then some—that Alejandro outlined. As students sought to mark themselves as “smart” and exceptional, they reproduced and reinforced those stereotypes and the barriers to belonging they represented for other Latinx people.

Some of those other people were those whom Succeeders loved. Lupita’s older brother was a landscaper. Her mom was a young mother who left school early and struggled with illiteracy. Alejandro’s parents were formerly undocumented. Students’ positioning of their exceptionalism as the product of the care and support of stigmatized families and friends formed the heart of their unfolding critique of national exclusion. In the latter half of the book, I track this critique through students’ relationship with their loved ones, beginning with parents.

Marina, an alumna of the program who came back to speak to students, framed her scholastic ambitions to her fellow Succeeders as the direct product of the fact that “my mom had dreams for me.” To enable those dreams, Marina told them, her mother made the sacrifice to migrate without documentation to Tennessee. Such framings of educational success are what Robert Smith terms the immigrant bargain, where educational success by children serves as intergenerational proof of the value of parental migration’s many sacrifices. Thus, Marina and others attempted to leverage their academic success as the product of their parents’ undocumented and otherwise morally devalued immigration, attempting to reclaim parents’ status as good parents and national members.

Moving beyond the immigrant bargain, Succeeders also began to question what constitutes success, especially in relation to their own caretaking for parents, siblings, and others. While educational achievement may have marked Succeeders as the right kind of college applicant and potential member of the nation, they began to see these accomplishments as most, and perhaps only, valuable in terms of the work education did to care for and kin others. Marina’s educational success was a way to reclaim her mother’s migration as valuable, but also a way to emotionally provide her mother with an object of pride. Lupita saw her achievement as a way to ensure younger siblings’ easier access to higher education. She, Isabel, and others not only modeled good study habits but also took concrete steps to guide their siblings through the educational pipeline, such as enrolling siblings in higher-quality magnet middle schools and volunteering at their schools. Educational accomplishment and guidance becomes a mode of familial care and one that positions Succeeders as valuable contributors to the family. As Lupita and others wrestled with easing the path for siblings, they began to see this educational care work as valuable in and of itself because of its role in sustaining immigrant families and their bonds of relatedness.

Succeeders extended this familial caretaking to their friends. The supportive space of the college access program, where students mixed across achievement levels and citizenship statuses, allowed students to gain a sense of “linked fate,” which Evelyn Simien describes as “an acute sense that…what happens to the group will also affect the individual member.” Some of this awareness had to do with the limits of legal citizenship and the educational meritocracy. Jenny noted it was “hard” seeing her high-achieving undocumented friends struggle to access higher education. Witnessing that struggle made her want to go to college even more: “I have the chance to go[…]there’s people[…]who don’t have it and want it. So, I’m not going to let that chance go to waste” (emphasis in original).

Additionally, like they had done with their parents’ stigmatized migrations, high-achieving Succeeders positioned their success as the product of the supportive friendship of struggling students. Standardized testing ace Alicia went as far as to state that going to college “wasn’t worth it” if her low-scoring best friend, fellow undocumented student, and loyal confidant, Pamela, did not also go to college. Most critically, they valued each other beyond their academic achievements. Succeeders saw the relational bonds they created in Succeeders as their more lasting achievement, particularly in light of a school system and nation that seemed to only care for achievers.

Isabel and the other Succeeders are now almost 30. They are no longer the high schoolers who worried about college admissions. Yet they continue to grapple with what it means to achieve and belong in the contemporary United States in myriad ways. They not only grappled with these social problems, but provided—and live—a trenchant critique to national exclusion that positions care as the way toward a better, if still imperfect, nation.