Article begins

Students, parents, and educators in Milwaukee continue a tradition of bilingual education activism and resist choice schools’ scaling up of linguistic subtraction.

At La Escuela Bilingüe Foster’s (Foster Bilingual School, pseudonym) first parent meeting of the year, Principal Núñez addressed a group of mothers and young children gathered in the school’s spacious 1920s-era auditorium. The second-generation Mexican-origin principal discussed the importance of the school and families working together to maintain the Spanish language, saying that “Nosotros no lucimos como güeritos pero hay muchos güeritos que están aprendiendo español. ¿Por qué debe ser como un lujo para ellos pero no algo para nosotros?” (We don’t look like white folks but there are a lot of white folks who are learning Spanish. Why should it be a luxury for them but not something for us?). Principal Núñez concluded her remarks by mentioning that private schools in the area may have some staff members who speak Spanish, but they were not bilingual schools. What historical precedents helped inform these contradictions around race and language within this place? How did school choice policies impact the current practice of bilingual education at La Escuela Bilingüe Foster (EBF)?

Between January 2018 and May 2019, I conducted dissertation research on the intersections, tensions, and potentials of bilingual education and school choice within Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the forcibly ceded traditional land of the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, and Potawatomi Nations. Milwaukee has a rich history of Spanish/English bilingual/bicultural education (BBE) as well as a storied role in school choice politics since it is the site of the United States’ longest running publicly-funded private urban school voucher program. As part of my dissertation work, I spent nine months at EBF, a K–8 bilingual public school on Milwaukee’s Near South Side with a high concentration (97 percent) of Latinx-identified students. Another component of the research involved conducting oral history interviews with people who participated in the movement to launch Spanish/English BBE in Milwaukee.

Image description: Mural with image of a woman with short brown hair underneath the sign, “Soy bilingüe bicultural y orgulloso de mi raza” (I am bilingual, bicultural and proud of my raza). To the right is a food stand and a couple dancing. To the left are historic images of Latin@s. Mural by Raoul Deal and University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee students.

Caption: Mural with image of Graciela de La Cruz underneath a sign of Latinx pride. Andrew H. Hurie

Unlike the city’s earlier German/English programs, Spanish/English BBE in Milwaukee was forged through public protest and community activism. Esperanza Gutiérrez, a community activist and retired bilingual social worker, explained that the early BBE movement sought to “abrir el sistema” (open the system) because public schooling in Milwaukee had reinforced English hegemony, ableist segregation, and Latinx subordination through its systematic tracking of Spanish-speaking students into special education. Throughout the 1960s, Gutiérrez’s father worked multiple jobs to afford private school tuition and thus avoid exposing his children to such miseducation. A veteran educator, policymaker, and social activist, Tony Báez described two “outbursts,” one led by Puerto Rican activists on the North Side and another by Mexican-origin families on the South Side. These public protests coupled with sustained community organizing compelled the monolingual white-dominated school board to significantly expand bilingual programming in 1974.

Recently commemorated in a mural celebrating the contributions of Latinxs in Milwaukee, Graciela De la Cruz was one of the first Spanish/English bilingual teachers in the public schools. She highlighted the Latinx community’s agency during the expansion of Spanish/English BBE in the 1970s, explaining that “Si la comunidad no te quería, no eras maestra” (If the community didn’t want you, you weren’t a teacher). Latinx-led activism thus transformed the public schools’ English-only orientation and helped to codify sustained support for BBE as official board policy.

Yet in the three decades since the establishment of Milwaukee’s school voucher program in 1990, the vast majority of voucher and charter schools in the city have offered English-only instruction, even in areas serving high concentrations of Spanish-speaking families. This is one example of how school privatization has resulted in a scaling up of linguistic subtraction for Latinxs in Milwaukee. While suggesting that the competition inherent in school choice might lead to public school improvement, De la Cruz also noted that voucher schools “no toman niños que tienen necesidades especiales” (They don’t take children with special needs). Choice schools’ ableist exclusion—the outright rejection or eventual counseling out of students labeled as disabled—was mentioned by various oral history participants as well as many bilingual educators at EBF.

With BBE and school choice both thoroughly institutionalized in Milwaukee, how did current bilingual educators at EBF make sense of their work? Unlike many other schools in the city, EBF offered a schoolwide bilingual education program. I noticed widespread support for instruction in two languages among teachers, teacher assistants, parents, and school administrators. In fact, some of the veteran educators at EBF had direct ties to the earlier movement to launch Spanish/English BBE, such as Principal Núñez who named Báez and De la Cruz as two of her mentors. However, the rationale for BBE differed among the school staff.

Some educators at EBF encouraged their students’ bilingualism by taking up discourses that had long pervaded the field of BBE: a separation of academic registers of Spanish and English was necessary for students to enter college and become socially mobile. As one teacher explained, bilingualism prepared students to “competir en esta era” (compete in this era). At the same time, educators at the public school largely denounced the exclusionary elements of charter and voucher schools, such as the choice schools’ denial of special education services and lack of bilingual programming. I understood this negotiation of competing discourses to reflect a broader neoliberal matrix of intelligibility that defines education as service to the market and individualizes educational decision making.

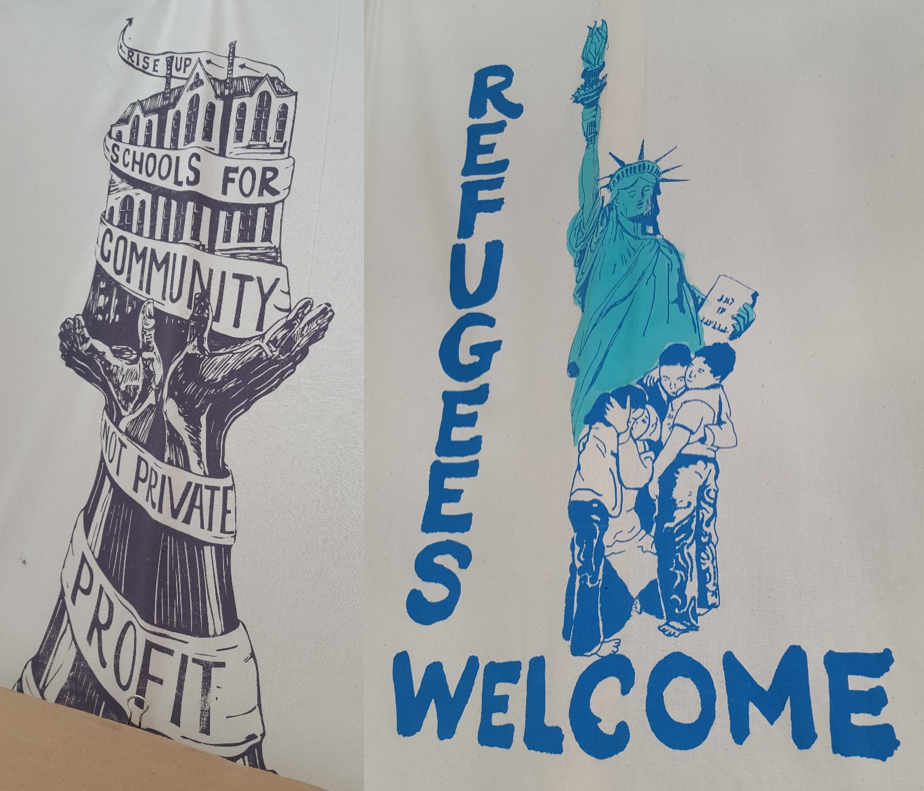

Image description: One sign features two arms reaching up and holding a building in their palms. A ribbon around the arms and building reads “Rise up schools for community, not private profit.” The other sign shows the Statue of Liberty with a small group of people in front of it. Words on the sign read “Refugees welcome.”

Caption: Milwaukee teachers’ union protest signs that Ms. Argueda used as models to inspire her students’ own sign-making. Andrew H. Hurie

Other EBF educators critiqued the exclusion embedded in Milwaukee’s implementation of school choice while also advocating for EBF students’ dynamic language use. These adults did not strictly enforce language separation; instead they modeled and welcomed the fluid use of Spanish and English as valid and valuable. For example, Ms. Argueda was a well-liked and enthusiastic teacher who had taken on various leadership roles both within and outside the school. I experienced her classroom as a vibrant space in which students expressed themselves freely across named languages. Ms. Argueda explained the theory undergirding her dynamic classroom language policy: “There are some students who mesh it up. I mean, I mesh it up [laughing]! I speak Spanglish, and that’s a tongue itself.” As a second-generation Latinx student growing up in what is now the southwestern United States, Ms. Argueda had experienced deficit-oriented schooling and aspired for her own students to experience school in more affirming ways. Further, she critiqued what she saw as “white privilege inside of the voucher system.” She explained that her partner had been the only African American member of a voucher school’s fiscal board, and when he began raising concerns about racial equity at the school, he was met with hostility from the other white board members.

This knowledge of bilingual education and school choice informed Ms. Argueda’s pedagogy rooted in social justice and leadership as collective action. Through her active participation in the Milwaukee teachers’ union, she acquired protest signs advocating for public education and refugee rights.

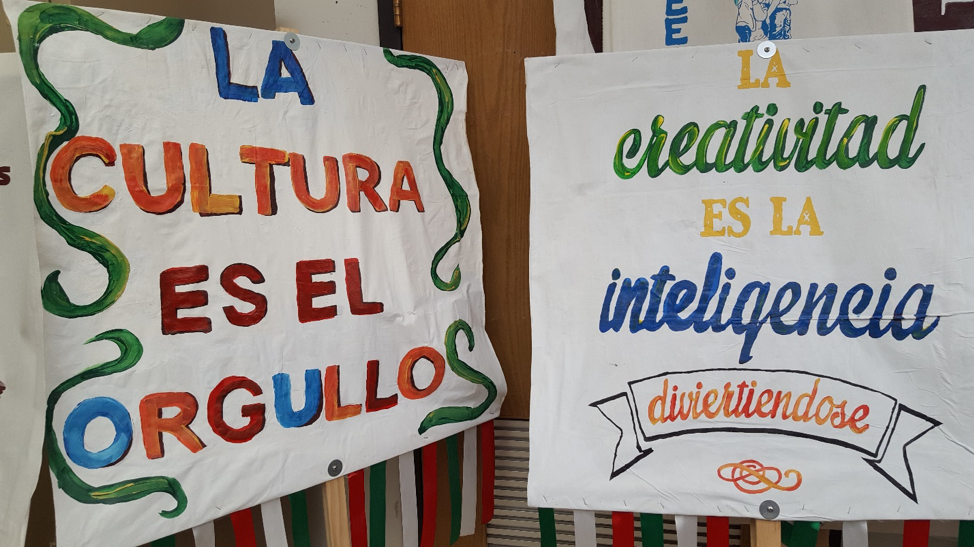

Ms. Argueda then used these signs as models for EBF students labeled as disabled, who created their own signs for the city’s annual Mexican Independence Day parade. Her pedagogy illustrates contemporary connections between BBE, collective action, and Latinx community practices. The emphasis on cultural pride suggests a continuity with prior Latinx-led social movements.

Image description: Two handmade signs are on display next to each other; both signs are written in various bright colors of paint. One sign reads “La cultura es el orgullo” (Culture is pride). The other says “La creatividad es la inteligencia diviertiéndose [sic]” (Creativity is intelligence having fun).

Caption: Two student-made signs for Milwaukee’s Mexican Independence Day parade. Andrew H. Hurie

As bilingual education expands throughout the United States, there have been increasing calls to center educational equity and protect bilingual education from appropriation by wealthy, white, English-dominant families who, to paraphrase Principal Núñez, see it as a luxury. My dissertation suggests that market logics have long enacted linguistic subtraction through school choice in Milwaukee. By examining bilingual education and school choice in tandem, my work argues that linguistic dispossession within Milwaukee occurs through complementary circuits in private and public sectors. That is, choice schools’ ableist exclusion and English-medium instruction complement the racializing discourses in the field of BBE that emphasize separate academic registers of Spanish and English. Crucially, the work also documents specific ways that EBF students, parents, and educators navigated these tensions and resisted linguistic dispossession.

This piece is based on Andrew Hurie’s dissertation, “Sustaining Bilingual Education Amidst School Choice Expansion and Linguistic Dispossession,” winner of the 2020 Council on Anthropology and Education Frederick Erickson Outstanding Dissertation Award. Find out more about this annual award and the nomination process on the CAE website.

Andrew H. Hurie is a lecturer of bilingual/bicultural education at Carroll University in Wisconsin. He completed a PhD in curriculum and instruction at the University of Texas at Austin. His research uses qualitative methods and critical theories to examine multilingual education policies and practices, with specific attention to different visions of educational justice.

Patricia D. López and Cathy Amanti are section contributing editors for the Council on Anthropology and Education.

Cite as: Hurie, Andrew H. 2021. “Sustaining Bilingual Education Amidst School Choice Expansion.” Anthropology News website, March 30, 2021. DOI: 10.14506/AN.1608