Article begins

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended everyday life in myriad ways across the globe, including disrupting employment, education systems, and family life. The transition to remote instruction underscores inequalities related to the digital divide and access to the tools of technology. At the same time, there is recognition of the stressors for teachers—and especially mothers—who are working from home while coping with their own children’s needs and instruction (Barnum 2020). This widespread pattern is evident in Mexico where maestra (woman teacher) is the most common career choice for women who attend university. In the state of Oaxaca, the overwhelming majority of 70,000-plus educators are women, thousands of whom are mothers.

These times with family allowed these rural maestras to reflect anew on the imbalance in their personal and work lives and the socioeconomic differences that affect their jobs.

The popularity of teaching for women is attributable to systemic sexism: Teaching is considered a “natural” job for women that complements the prescribed maternal responsibilities of socializing and nurturing children. Moreover, ideally maestras’ work schedule allows mothers to be home with their children when school is not in session. Yet as one mother told me, conditions in rural Oaxaca result in maestras “spending time with the children of others while others are with our children.” The perspectives of two Oaxacan maestra–mothers during COVID-19 school closings regarding their own and their students’ experiences with remote teaching shed light on ways that their public and private roles intersect—ways that are not necessarily obvious to those unfamiliar with the unique challenges that rural maestras face.

Teaching is an attractive career in Oaxaca, a state with a 2/3 poverty rate. As federal employees, teachers enjoy job security, a relatively high salary, and considerable federal benefits. Nevertheless, there are drawbacks. Mountainous topography, poor road conditions, and difficulties with transportation often mean that rural teachers stay in isolated villages during the work week. They arrange for their children to live with relatives in communities with greater access to basic services (e.g., health clinics, electricity, indoor plumbing) and post-elementary schools, and return to them on weekends. The gendering in attitudes toward this practice is obvious: For fathers, absence from home is viewed as a necessary part of the job. But in parallel with long-established ideals in which “good mothers” are children’s primary caregivers, maestra-mothers say that they are routinely criticized for “neglecting” or “abandoning” their children while working away from home. For these women, being viewed as an “absentee mother” is a cruel manifestation of what Maria Tamboukou aptly terms the “paradox of being a woman teacher” (2000, 472). The closing of Oaxacan public schools on March 23, 2020, further complicated the lives of nearly one million students and their parents and exacerbated the already complex working lives of teachers—and especially mothers—who are assigned to remote communities.

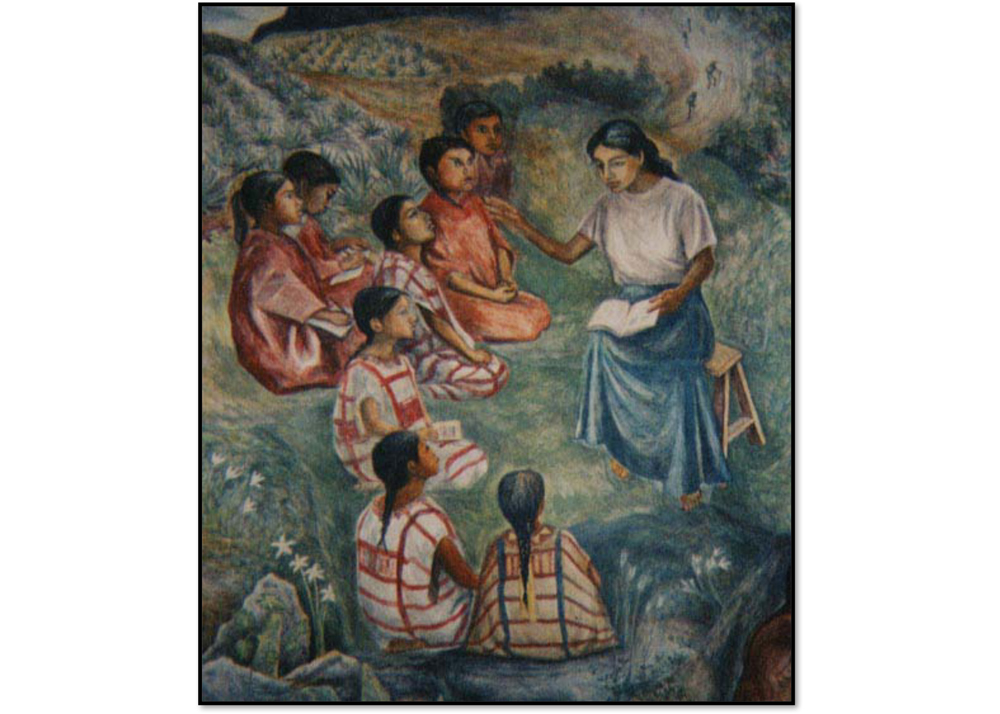

Image description: Rural maestra sits on a stool surrounded by her attentive students during a school lesson in the Oaxacan countryside. A book rests in her lap and she raises one hand while her eight students sit on the ground and watch her.

Caption: Mural in Governor’s Palace, Oaxaca City. Jayne Howell

Contrasts in access to remote learning

Linda, a 35-year-old sixth grade teacher, stays during the week in a village 2 hours away from her family home. She and her husband, who teaches in a different community, typically come home on Friday afternoons and return to those villages on Mondays. Their two children live with her mother while she is away, paralleling a pattern also reported for Oaxacan mothers who migrate to the United States (McGuire and Martin 2007). Her son is a senior in high school and plans to enter university next year, and their daughter is in middle school. Linda said that she’s “grateful that the pandemic has given me time with my husband and children. It’s good that we’re all together.” Her children have access to computers, smartphones, and the internet, which allowed them to receive televised and online programs produced by the federal Ministry of Education. She observed that they “struggle with televised classes. It’s not like in the classroom, where you ask questions if you don’t understand.” Linda told me that as teachers, she and her husband can help them with their homework. She reflected that this “makes me think about my job. I miss seeing my students’ faces.” Most of her students lack access to the internet or televised courses, and she is not sure they are able to listen to lessons the state government broadcasts through the radio.

Linda had left two-weeks of assignments in math and Spanish with her students when school closings were announced, expecting she’d return after the Holy Week holiday. However, with the extended closure, she must communicate via a parent who can access WhatsApp when working outside the village. She spoke of her “fear they are having trouble with their homework. And who can help them? Many of their parents, their grandparents, [speak an indigenous language and] don’t speak Spanish.” She feels “guilty” that she and her students are not in contact, as she fears many will not finish sixth grade without her there to encourage them and worries “that they will have little incentive to return to school in the fall” as many plan to eventually migrate to the United States.

This reality has strengthened both women’s resolve to get back to their students for face to face instruction in the classroom.

Naomi, a 50-year-old with a teenage daughter, Xochi, has similar concerns. She teaches middle school in a community located 3.5 hours away from her family’s home. Like Linda, she tries to ride with a colleague to limit the time and money invested in taking multiple forms of transportation to reach the village. Due to Xochi’s health problems that preclude travelling, Naomi’s husband became the full-time caregiver a decade ago. Her recently deceased mother-in-law (who lived next door) was an important maternal figure and allowed Xochi to “talk to a woman” because her mother had no phone access in the village where she taught. Watching the challenges her daughter faces while completing coursework online, with access to her teachers only when they have internet access, causes Naomi to reflect on how her students are coping without a means of contacting her.

While working from home, Naomi has arranged to send a printout of assignments with a physician who goes to the village each Monday. The doctor leaves these at a small stationery store where the students can pay to have a copy made, and she brings completed assignments to Naomi on Thursday night. Naomi develops lessons during the week, and appends the weekend grading. She has this feedback and new materials ready to be picked up on Sunday night. She described “trying to make sure my students learn, even without daily instruction” and feeling “frustrated” that she is not in the classroom to “motivate [the] students to stay in school.” She explains, “life is hard for those children. They’re in the fields with machetes or tending to livestock. School is a time when they can see their friends and talk about their plans. They get a chance to imagine a different future.”

Perspectives gained

Ultimately, these times with family allowed these rural maestras to reflect anew on the imbalance in their personal and work lives and the socioeconomic differences that affect their jobs. Their extended absences come with an emotional cost that exacerbates the tensions faced by countless working mothers who are both childcare and economic providers. However, they and other maestras in this situation have said to me that they become “resigned” to the temporary family separation their jobs demand. They stress that their income allows them to support their children’s schooling. In this case, each mother’s children have a computer and internet at home that they use for homework throughout the school year, and for receiving and sending assignments during the pandemic. I suggest that this underscores that the financial benefits of mothers’ labor are a critical dimension of what many women who work outside the home, and their children, view as an integral dimension of what it means to be a “good mother” in the twenty-first century. And yet, although these mothers are appreciative that the quarantine has allowed them to spend extra time with their own children “like other mothers do” (in Naomi’s words), these dedicated teachers are acutely aware of and troubled by the contrast between their children’s privilege and their students’ lack of access to remote classes. Each has seen firsthand that “Oaxaca is not equipped for online instruction” as Naomi lamented. This reality has strengthened both women’s resolve to get back to their students for face to face instruction in the classroom. Even if doing so entails sacrificing precious time with their own children.

Jayne Howell is professor of anthropology and co-director of Latin American studies at California State University, Long Beach

María Lis Baiocchi, Leyla Savloff, and Megan Steffen are contributing editors for the Association for Feminist Anthropology’s section news column. For more information or with interest in publishing through AFA on AN, please contact us at [email protected], [email protected], or [email protected].

Cite as: Howell, Jayne. 2020. “Teacher-Mothers’ Lessons Learned During the Quarantine in Southern Mexico.” Anthropology News website, June 30, 2020.