Article begins

As a visual artist and cultural anthropologist, I create installations that blur the line between art and ethnography. For over 20 years, I have created works that use my training in both fields to expand the ethnographic text and its audiences. This interdisciplinary practice, which combines visual art and ethnographic research, opens opportunity to conduct and present research in a unique way. Here I use two interdisciplinary art projects to discuss observing and participating in the creation of both the artwork and ethnographic knowledge; embodied forms of knowledge produced through art making; and art exhibits as forms of public anthropology.

Creating images and learning about exile

Geographies of the Imagination is an art installation dedicated to revealing the internal images of exile. It is the product of collaborative art making with nine Chilean political exiles, in which I was the creator of the images guided by the exile participants and by the process, which afforded deliberate pauses for us to reflect on the work and share memories.

For over 18 months, during my tenure as artist in residence at the Center for Art and Public Life (2007–2008), I created with the Chilean exiles nine videos and 23 monoprint banners depicting their memories of and reflections on long-term exile. The participants arrived in California over 30 years ago, having been expelled by the regime of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet (1973–1990) because of their ideas or political affiliations. They joined this project because they wanted to recall the past, and also to make their stories public as a response to the silence about their exile maintained by successive post-dictatorship governments.

The participatory method consisted of a series of sequential stages. My first meeting with Jaime was at his home and was to record his memories of forced migration and discuss a preliminary sketch of his banner. During this meeting, he described the effects of forced migration on his sense of self and belonging. He said:

I feel divided. I lived in two different Chiles and here too. I feel that I stayed somehow in the middle. I would love to go to Chile and live there because life is more placid, quiet there. I am going to retire soon. There are two Chiles: the Chile of my memories and dreams, and the Chile that changed and that expelled me and to which I don’t belong. I feel that this country [the United States] has treated me well, that I have done more here than I could have done in Chile, that my rights are respected here, that social classes matter less than in Chile. But I also feel that I don’t belong here. I am an outsider and I will always be one here…

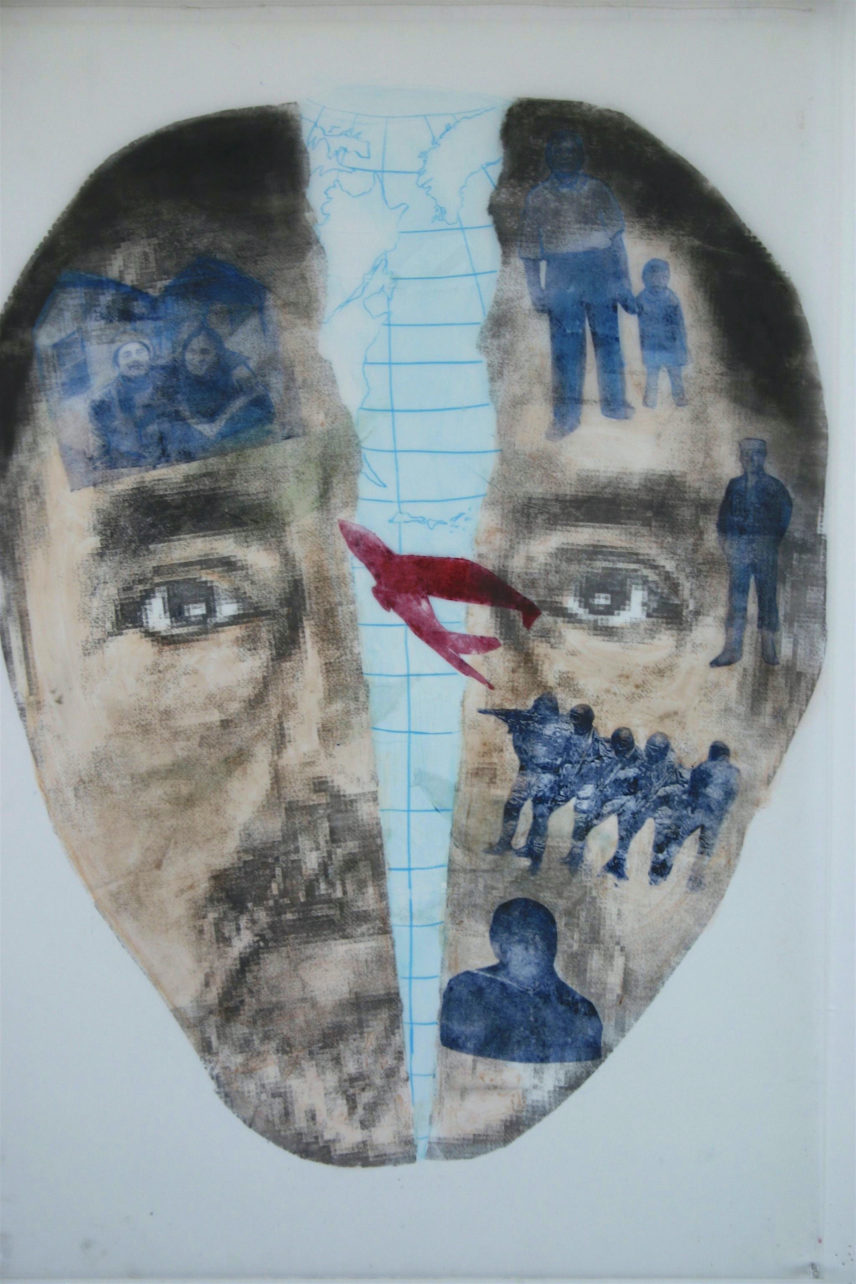

The second stage was to create the first image based on Jaime’s description of his divided self. I used a recent photograph of Jaime, tore it in half, and created a photo etching of the two halves of his face.

For the third stage, the exiles reviewed the images and judged their fidelity as representations of their memories as well as the aesthetics. These conversations were rich with ethnographic information about the exiles’ internal views of forced migration as the images triggered further reflections on the past. Jaime’s first response to the image of himself was to reminisce and evaluate his life in both countries. As he contemplated the two halves representing his life in Chile and the United States, he expressed a desire to fill them with his most important moments in both places. I suggested the use of photos that later I would etch in. For his life in Chile, he spent hours selecting from hundreds of photos as he talked about the past. He selected three: one at age four at a park with his father, another as a fifteen-year-old sailor when he joined the Navy, and one taken at the prison where he was held for three years because he refused to join with the armed forces that implemented the coup to overthrow the government of Salvador Allende. For the side representing the self that belongs to the United States, he surprised me by selecting just one photo (posing with his wife and daughters in front of his house), although he has lived most of life in the United States.

In our next meeting, Jaime contemplated the new image and cried, “I don’t belong anywhere!” He later mused, “I belong to a third place, which is neither here nor there.” Later, I widened the space between the two halves of his face leaving an empty space to represent Jaime’s third space. When he saw this image, he commented that his place of belonging is not stationary, as characterized by a constant moving between the two selves. I asked him how I should represent his traveling self. He wanted a bird. But he also wanted an airplane. I created a bird that also looks like an airplane and connects his two sides. For the background of his split self he asked for the image of a map that represents Chile and California combined.

These meetings also became arenas in which the exiles and I verified our mutual understanding. By seeing how I portrayed them in the images I created, they had a glimpse of my views of them. My assumptions about their backgrounds were often corrected, and I had to create new images. While sometimes these moments were uncomfortable for me, as I had to face my misconceptions, they were also a fertile ground for the mutual creation of empathy and rapport.

As ethnographer and visual artist, I was able to participate and observe as knowledge emerged and evolved through our interactions, through the exiles’ responses to my input and me to theirs. I could observe and use my senses and skills as a visual artist in the creation of this changing and emergent knowledge.

Creating embodied forms of knowledge

Atlas of Dreams is a project comprising ethnographic research on memorable dreams and visual art that aims at uncovering the emotional aspect of cities. For seven years, with the help of students at the California College of the Art, I interviewed over 400 residents of the San Francisco Bay Area about their memorable dreams—those that remain in the minds of people because of their strong imagery and emotional content. The dreamers classified their dreams according to the following categories: nightmares, bizarre, wondrous, healing and consoling, premonitory, repetitive, and lucid dreams. To visually present the distribution of the different forms of dreams in cities, I created artistic maps to show the location where participants narrated the dreams and at the same time capture the emotional traces of their narratives in the streets.

Dérive or drifting, a technique developed by the situationists (a mid-twentieth-century radical alliance of European avant-garde artists and writers) to uncover the emotional aspect of cities by walking without an itinerary and engaging emotionally and imaginatively with the surroundings, provided one method. The second technique I used was frottage, the act of capturing hidden textures of a surface by taking a rubbing with paper and pencil, developed by the surrealist Max Ernst. Both techniques gave me the opportunity to experientially and conceptually understand the process of dream formation as described by the dream researcher Ernest Hartmann (2014), who viewed the imagery of dreams as metaphors for the dreamer’s emotions, created by our minds under the guidance of our emotions.

I drifted through the areas where I collected the dreams by car and on foot, each engendering different feelings and experiences. For example, as I drove, I was able to view the length of the street and anticipate its coming end. I felt the shape of the curves and corners from the sensations created by my body while I made turns. I transported these feelings into the creation of the grid or layout of the streets by using a knife instead of a brush or pen. Walking enabled me to feel and capture what I perceived as emotional instances in the streets that then guided the creation of the artistic maps.

As I walked in a dérive through Lake Merritt in Oakland, one of the cities of the Bay Area of San Francisco and where I found clusters of dreamers’ narrations of nightmares and night terrors, I encountered a man who was standing in front of a memorial shrine and mourning the death of a gang member who had been recently killed at the lake. Witnessing this expression of suffering made me reflect on the large number of homicides that Oakland had suffered in the last decade. A few days later, I noticed that the city employees had removed the death memorial, breaking the votive candles and leaving behind a few pieces of glass, which I gathered. Using the surrealist technique of frottage, I placed these pieces of glass under paper and traced their shapes as a way of bringing out the hidden emotions of the city and the emotional traces of the dream narratives.

After several dérive walks, my capacity for absorbing emotions from the streets became more acute and I entered a state of sensibility akin to the paranoiac-critical method of Salvador Dali, in which the artist soaks up what she sees and enters a state dominated by a flow of images and sensations. Memories and feelings associated with the dreams I had collected tinted my encounters in the streets, dissolving the boundaries of my internal world with the surroundings. I incorporated these experiences into the creation of the maps, injecting the center of the maps with the emotions I felt. In this manner, I replicated and experienced bodily a process of dream creation, from the use of emotions to the creation of dream images.

Exhibits as public anthropology

Art exhibits socially, relationally, and experientially transmit knowledge to audiences; they can be powerful forms of public anthropology. These exhibits can produce spaces for altering understandings of the world and potentially generating social change (see Bennett 2005, Bourriaud 2006).

I have these forms of transmission during the opening reception for Geographies of the Imagination at the Oliver Art Center Gallery of the California College of the Arts (October 24, 2008–November 28, 2008), which I designed to evoke the experience of long-term exile and migration. The installation took up two rooms in the gallery. In the main room nine video monitors stood on stands aligned in the shape of a V. Each monitor played the personal stories of one of the exiles and their reflections on exile and nostalgia. Above the monitors hung 32 monoprints depicting the exiles’ memories of forced migration. In a separate room furnished with chairs and tables, visitors could trace their own journeys and migrations on the outlines of geographical maps.

Audience members reflected on their own experiences and were also affected by the ways others engaged with the installation. People sat with friends and family and shared their journeys. For example, a man used four maps to trace his journeys around the world during his 30 years working as a merchant marine and through doing so showed his wife all the places he had visited. He also reflected on his new life as a sedentary retiree and his recent heart attack. The act of seeing others engaged in this activity created a different awareness for the audience about their own migration, identity, and sense of belonging. A woman commented that seeing parents showing their children their places of origin and tracing their journeys made her feel that the stigma of being an immigrant had been lifted from her.

As audiences at the installation, the exile participants expressed a feeling of unity with one another as they recognized commonalities in their experiences and feelings. This awareness led them to organize future meetings to talk about their experiences of exile. Although most of them were familiar with the general set of events and circumstances of some of the other exiles, this was the first time that they heard the stories of many other exiles.

The production of the artworks for public display also affected the exiles during the creation process. It made them aware of audiences within and outside of their communities. They imagined audiences as they worked on the art, to address those who had caused their situation of exile: the government of Augusto Pinochet. They addressed Pinochet directly or indirectly by creating counterimages or counternarratives to oppose those they perceived were created about them by the government.

The hybrid work of combining visual art and ethnographic research gives me the opportunity to observe and participate in the creation of ethnographic knowledge through the making of art objects. Through the use of different art techniques, I have also been able to experience knowledge through my senses. And exhibiting these works in galleries has given me a new form of transmitting knowledge, which produces immersive and sensorial forms of understanding in social settings that differ from the intellectual and solitary reading of texts.