Article begins

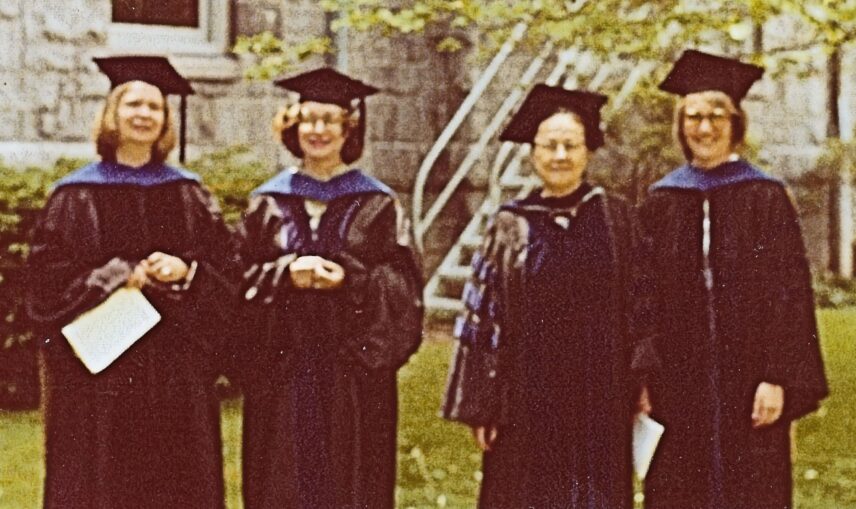

In case you hadn’t noticed, the Association of Senior Anthropologists (ASA) is being overtaken—at least in a figurative sense. Several women who all got our doctorates from Bryn Mawr College (BMC) are increasingly active in the Association, including the Board. I have had the honor of being ASA’s secretary for the past six years. Soon Laura Zimmer-Tamakoshi, another BMC graduate, will take over, ably supported by Bryn Mawrter Maria Cattell, who becomes ASA president at the same time. Though I didn’t meet them while at Bryn Mawr, I’ve enjoyed getting to know them as senior anthropologists and realize how much we have in common. We were at BMC at different times, had different advisers, and carried out ethnographic research in very different parts of the world. What we shared, however, was a validating graduate experience which was particularly rare for young women half a century ago, including (as Alice Kehoe’s recent memoir vividly illustrated) in our discipline. Here I’d like to share just how important that experience remains for me personally as well as professionally. I suspect the others would be happy to add their own impressions.

It was 1970 when I started graduate work after undergraduate training at London University (Bedford College). There I specialized in medieval, particularly Byzantine, history, obviously attracted to other times and places though this only became clear to me after graduation in 1965. Then, through the auspices of Voluntary Service Overseas, I took my first ever plane ride, to Sudan to become an English teacher at Wad Medani Girls School, 150 miles south of Khartoum on the Blue Nile. A Muslim boarding school for girls, it was one of only five in the then-largest country in Africa, attracting students from a wide area who had passed the tough entrance examination. My duties included daily literature and language lessons to the two junior level classes, as well as an array of extracurricular activities: dramatic society, tennis and volleyball lessons, organized visits to the British Council library, and boarding house supervision. Lessons were held six days a week and on Friday, our day of rest, I was often invited home to meet the students’ mothers and sisters. I loved every minute of it, and when a visiting examiner remarked how I reminded him of an anthropologist, I found my vocation. I also realized, from the paucity of publications about women in this region, that I had found my ethnographic home. Indeed I have spent much of my career living in different parts of Sudan, researching and writing about ordinary women’s lives. Equally important, this is where many of my closest friends (some going back to 1965) still live.

Formal training in anthropology came a few years later. By 1970, married and living in southeast Pennsylvania, I was ready to begin graduate school. I learned there were two possibilities in the area: University of Pennsylvania and Bryn Mawr. From their catalogs I was not surprised to learn that Penn had no women faculty in the anthropology department—typical at that time—but found Bryn Mawr had two, both full professors. After coming to the decision about graduate work via a male-dominated undergraduate training and hands-on experience in the segregated society of northern Sudan, I had no hesitation: Bryn Mawr was clearly the place to go.

It more than fulfilled my expectations. Frederica de Laguna and Jane Goodale were formidable mentors for all their students, but particularly for women. Early on I remember Jane saying: “We’ve a lot to do. Over half the world is female and we hardly know anything about them!” Jane was just celebrating the publication of Tiwi Wives (1971), and the notion that women might hold their own distinctive understandings of how their culture worked was heady stuff for female anthropology students in 1970, who knew things were not so different in their own societies. Jane’s understanding of women’s lives indeed extended to our own society. When I found myself expecting my first child at the start of my third year of course work, I told her I should probably drop out. “Why?” she asked crisply. “Are you planning to get sick? Women all over the world get pregnant all the time, and just keep on going.” I kept on going, did not get sick, and together Jane and Freddy were enormously supportive as I prepared for final examinations and my defense, in the month before the baby arrived.

Most important for me personally was the influence of Frederica de Laguna, who became my adviser sometime during my first year. For all students, Freddy was an inspiration: an encyclopedic fund of knowledge whose acclaimed Under Mount Saint Elias (1972) was published around this time, accomplished mystery novelist as well as ethnographer, and first female president of the AAA. Less of an overt feminist than Jane, Freddy was nonetheless sympathetic to the traditional biases against women in anthropology, ready to make small and major contributions to our success. With her help, I found support for dissertation field research, for finding a fulltime teaching position, for a delay in completing my thesis (after the birth of my second child), and for understanding as I rushed to complete my dissertation before she retired. She could also be a tough taskmistress. Can I ever forget how, as I prepared for prelims and asked her what was my main area of weakness, she retorted: “Well, you just don’t know very much!” Years later I was visiting her at her retirement home in Haverford and over a martini or two at dinner, she complained what a tough mentor Boas had been. I replied that she too could be demanding and reminded her of this exchange. She clapped her hand to her mouth and said, “That’s Boas! Straight Boas!” before denying she had said any such thing.

BMC’s graduate program in anthropology was never large—there were just four full-time faculty, plus an associate in linguistics—and we all got to know each other well during our time there. We also were well aware there was nowhere to hide: everybody made regular contributions to seminars and discussions, including the thrice-weekly informal lunches in the anthropology lab where faculty and students participated in what seemed to be an extended conversation. Department visitors—I remember Raymond Firth and Margay Blackman—and visiting faculty from Penn (Pete Hallowell, Igor Kopytoff, and Bill Davenport) often joined in, broadening the discussion theoretically as well as globally.

Also influential were fellow graduate students, particularly those close to completing their studies. Carol P. (Hoffer) MacCormack defended her work on the Sherbro during my first year at Bryn Mawr and I recall lively conversations about her research, combining travel with family demands, and advantages women brought to the field situation. Like Jane, Carol had observed in Sierra Leone how western perceptions of gender were far from universal and her research experience offered ways of unpacking this. Annette Weiner, another grad student, mother, and future AAA president, was only a couple of years ahead in coursework, but seminars in which she participated were invariably more stimulating than those without her. In 1972, we both went off for our first fieldwork, Annette to the Trobriand Islands and I to the Northwest Coast. Both before and after our return, she was a major sounding block for ideas and reflections. She also learned early on the advantages women researchers brought to field research, witnessing the importance of women’s mortuary exchanges in the larger social fabric, something Malinowski had either dismissed or missed altogether.

Other fellow grad students helped reinforce the collaborative atmosphere we took for granted at BMC. To single out but a few, Carolyn Beck joined us in 1971, shortly after the birth of her second daughter, and shared confidence-building maternity clothes for my oral defense, as well as stimulating discussion about African economic systems. Mimi Kahn accompanied me on my second field trip to Kyuquot in 1974, offering important insight into our research as well as help with an infant. Sue Roark, recently widowed and with a young daughter, shared my interest in Native American studies. Her work on the pow-wow networks of Oklahoma offered important insight into potlatch exchanges I witnessed on Vancouver Island.

Graduate school for we seniors was a long time ago. It helped shape us as anthropologists and offered us our initial network of peers and role models, but once completed it was up to us what we did with that training. The various paths taken by students from the same program are perhaps testimony to the success of that program, and the very different careers of Maria, Laura, and me reinforce that point. At Bryn Mawr we were all encouraged to think well outside the proverbial box, to follow our own interests as people as well as researchers, something that was rare at the time. Equally important, we were given the assurance to believe in our own abilities to contribute to what was an exciting and relevant discipline. Those who attended other schools may find satisfaction in revisiting those programs and assessing the changes that have occurred there over the past half century. For various reasons, Bryn Mawr graduates don’t have that luxury. After a mere three decades, the graduate program in anthropology was terminated, ostensibly for economic reasons. Whatever the reason, those amongst us who benefitted from the relatively brief flowering of BMC’s training continue to draw on the professional and personal confidence the program inspired.