Article begins

Compadrazgo, from the gender-neutral gloss compadre in Spanish, literally means co-parenthood (i.e., shared parenthood). In its most elemental sense, the term refers to the spiritual and ritual kinship established between the parents and the godparents of a child over his/her baptism, which is the first of the seven Roman Catholic sacraments, an archetypal rite of passage. Common throughout Latin America, this sociocultural institution enmeshes biological and symbolic-religious parentages into a kin-like interpersonal relationship. It further evolved into an ever-expanding network of systemic “kinship by choice” characterized by a flow of highly respectful social and even reciprocal material responsibilities, especially among the adults involved.

The elaborate compadrazgo system has been studied mainly by sociocultural anthropologists, chiefly in Mesoamerica and the Andean region. Sir Edward Tylor, the pioneering British anthropologist, was an early commentator on Mexican ritual kinship, and twentieth-century ethnographers, such as the late Hugo Nutini (1928–2013), theorized the cultural phenomenon in the countries south of the Río Grande. Researchers have reported countless variations of religious, quasi-religious, and even secular compadrazgo occasions throughout the Americas. (Interestingly, it is not found in eminently Catholic societies, such as Ireland, and compadrazgo traditions in Spain and Portugal tend to be less intricate than their “New World” counterparts, yet it is prevalent in the Philippines, which was colonized by Spain).

For Anglo-Catholics, as well as the followers of other Christian rites that practice baptism—such as Anglicans and Episcopalians—the individuals involved in these ceremonies are not expected to form kin-like groups. However, in much of Ibero America, participants are typically drawn into a quasi-sacred relationship that at times supersedes even consanguineal and affinal relations. The terms “compadres” (masculine/neutral) and “comadres” (feminine) have become tantamount to “chums” or “buddies”—sometimes even “accomplices”—in everyday discourse throughout the region.

Despite the continued importance of compadrazgo among Latin Americans (as well as Hispanics in the United States), it seems that many contemporary anthropologists tend to either overlook the phenomenon or view it as a passé subject. This is somewhat ironic, given that compadrazgo traditions have proven to be both pliable and enduring. Here, I present some observations that connect contemporary practices with long-standing issues and discussions in the study of compadrazgo.

One form of change and variation that anthropologists might examine relates to who participates in compadrazgo. Both religious-based and secular types display vast geographic variation and are often subject to rather arbitrary local parishes and/or folk interpretations. The primordial baptism ceremony symbolizes a cleansing rebirth that marks a child’s initiation into the world’s Christian community. Technically, only one adult sponsor of either gender is required by Catholic Church rules, but customarily, both a man and a woman stand as godparents. Lately, I have observed among US Hispanics in my own community in northern New Jersey the addition of more than one duo as symbolic godparents at the ceremony.

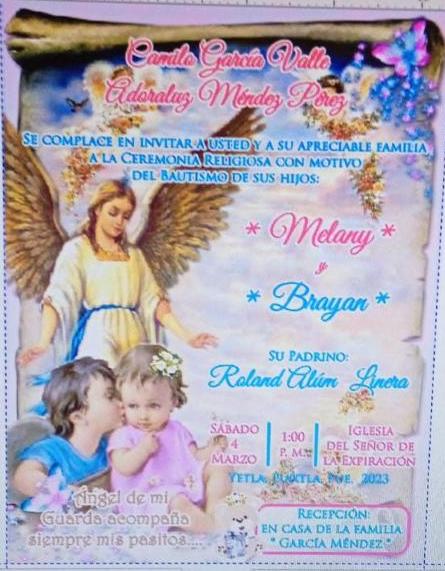

Another set of changes and continuities has to do with the responsibilities that godparents have toward the neophyte and their compadres. In theory, the godparents are responsible for the child’s religious upbringing. Although there are no legal obligations, godparents are morally expected to raise the child in case of the parents’ absence. They are also usually expected to assume certain financial responsibilities for the godchild, as well as for the fiesta that normally follows the ceremony. I experienced these expectations myself upon standing recently as godfather to two Mexican siblings in a remote rural hamlet of the state of Puebla (see image of the baptism invitation below).

The relationship between the five individuals involved is characterized by an elaborate etiquette that includes expressions of deference, trust, and reciprocity of various kinds.

This reverent conduct among the adult co-godparents encompasses addressing each other as “compadre” or “comadre,” respectively, while adopting the formal and more respectful usted form that replaces the informal tú in Spanish.

Although baptism co-godparenthood remains the classical form of compadrazgo, these types of ties grew exponentially to incorporate a large number of occasions throughout the region. Examples include other Catholic sacraments, such as first communion, confirmation, and matrimony, as well as nonreligious rites of passage, such as school graduations and quinceañeras, along with quasi-religious rituals that bless pets and other animals, as well as objects (e.g., a house, a tractor or an automobile). In the Mexican state of Tlaxcala alone, Hugo and Jean Nutini reported discovering over 30 occasions for compadrazgo.

At the same time, there seems to be much continuity when it comes to the functions of compadrazgo, which include, in some cases, the reinforcement of social hierarchies. The question of who is included in co-godparent bonds is subject to regional variation. In some areas, for example, all of the co-godparents of an individual may be considered mutually compadres, too, although it is understood that this is ultimately optional. A Mexican-born anthropology colleague reported to me that even the parents of her co-godparents treated her as an instant comadre. Yet the basic social functions remain, to wit: (1) extending personal networks and family alliances, (2) intensifying existing ties among consanguineal and affinal kin and friends, (3) fostering harmony and social solidarity (e.g., mutual support in difficult times), and (4) enhancing local prestige (more godparents means greater prestige, i.e., social capital).

Further, scholars have distinguished between horizontal and vertical forms of compadrazgo, the former involving co-godparents of a similar social level (e.g., class, ethnicity), and the latter referring to selection of co-godparents from a higher status. Compadrazgo among equals serves to bolster group solidarity, whereas vertical compadrazgo could establish and reinforce patron-client relationships. A case in point was dictator Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic (1930–1961), who stood as godfather to hundreds of children baptized en masse, with him expecting political loyalty from the new ritual kinspeople. I met some of these individuals during my own field research there in the 1970s.

Although some researchers might have forecasted the demise of compadrazgo among Latin Americans due to economic development, secularization, internal and transnational migration, and the growing presence of Protestant and evangelical churches in the region, compadrazgo has endured and adapted to such changes. Instances of compadrazgo do not seem to be diminishing in ever-expanding Latin American cities or, for that matter, among Hispanics in the United States. Scholars have also found that compadrazgo ties often survive after conversions to Protestantism. Besides, even in the case of baptism, according to Catholic Church rules, only one godparent needs to be Catholic.

New communication technologies have also offered novel opportunities for the establishment and continuation of compadrazgo ties. Nowadays, an overseas-based couple might participate remotely as baptismal godparents at a ceremony taking place in, say, South America. At the church, there would stand proxy godparents—called padrinos de brazos (literally, “arm godparents”)—who ceremonially hold the neophyte in their arms for the ritual, though the emigrants’ names still appear in the baptism certificate as the rightful godparents. Resources could flow from the overseas padrinos to the new ritual kin, given that, again, there is an expectation of noblese oblige.

While some foreign anthropologists might tend to overlook compadrazgo, lately I have found that many Latin American anthropologists still give proper weight to its analysis. The two main characteristics of compadrazgo, its plasticity and its inconsistencies, have allowed the institution to meet the challenges of a dynamic and postmodern world. From a social-scientific standpoint, compadrazgo offers a unique opportunity to empirically study a “kinship by choice” tradition in a time of rapid social change.

Joseph Feldman is the Society for Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology section editor.