Article begins

On May 27, 2020, RPP (Radio Programas del Peru), one of the country’s most recognized and trusted news outlets, published an article entitled “Home Deliveries: An Illegal Practice Investigated by Cusco Authorities.” Vanessa, a midwife assisting expat women in Cusco and the Sacred Valley, sent me the article via WhatsApp. She accompanied it with a furious voice note: “Look at this! They [the reporters] only spoke to doctors and didn’t do their research.”

I was surprised by Vanessa’s anger. My conversations with Runa (Quechua) women on reproductive health in the Cusco region, between 2019 and 2020, had led me to believe that home birth was, indeed, illegal. As we peeled lima beans, washed quinoa, and made chicha (corn beer), women recalled being threatened with fines and jail time by medical personnel at rural health posts if they refused to go to the hospital to give birth. This pressure made little sense to me, as health services for rural women are scarce in Peru. Moreover, hospitals are not always safe places for Indigenous women.

Many of the mothers I spoke with recounted being abused and insulted while in labor. Doctors and nurses made derogatory comments about their lack of cleanliness, the smell of their bodies, and the number of children they had. Echoing findings on Peru’s mass forced sterilization campaign of Indigenous women in the 1990s, some women reported being dehumanized and animalized by health personnel. One young woman, Imelda, recalled being berated by nurses until she “consented” to going on birth control after her C-section. “Do you want to breed like a cuy [guinea pig]?!,” she remembers them yelling, comparing her to the prolific Andean animal.

Despite its apparent illegality, I did come across Runa women who still wanted to birth at home. “I would rather die than give birth in a hospital,” Rocio said, rubbing her low and heavy belly. I was taken by the force behind her words. For Rocio, dying at home was not the worst thing that could happen. Birthing in a hospital might save Runa women’s lives, but given the racist medicopolitical context, it might also mean being stripped of their humanity and dignity. The memory of the forced sterilizations was never far from Runa women’s minds—a fate that, for Rocio, was worse than death.

Another one of my interlocutors, Maruja, birthed all three of her children at home. She told me that during labor her family set up a warm and dark birthing room. The midwife prepared an herbal steam bath for Maruja to squat over to help relax and open her body. In this emotionally, psychologically, physically, and culturally supportive safe space, Maruja gave birth without complications.

Yet not every Runa woman has the means for a good home birth. I found that home birth in Cusco is a privilege reserved for women with close kin ties and funds to pay midwives. When we met, Inés was in her early thirties. Both of her parents had passed away, and her close kin had migrated to the city. Her husband was out of town when she went into labor with her fourth child. Unlike traditional Runa families in which women maintain the power of the purse, Inés’s husband controlled the money in this evangelical family. The local midwife was also out of town, and without funds to bring in another midwife to assist in the birth of her baby from a neighboring community, Inés found no other choice but to go to the hospital.

Once there, cold and alone, her labor stopped. Vanessa, the midwife, explained, “The cervix is a sphincter like any other. If a woman is cold, uncomfortable, or scared, her body will not open.” When Inés’s labor stopped, she was forced out of the hospital and into a local hostel where she waited, alone, for her labor pains to return. When she ran out of money on the third day, she returned to the hospital, where staff finally induced her.

Given the abusive treatment faced by birthing Runa women and the few resources allotted to provincial Peruvian hospitals, it seemed odd that women could face jail time for giving birth at home with a midwife. It also made little sense to me that there seemed to be so few midwives in an area such as Cusco with such a strong historical tradition of midwifery.

As in other parts of the world, in Peru, the sphere of biological reproduction is politically thorny. In this context, population science and child and maternal health are historically tied into larger geopolitical and economic dynamics. In the Peruvian case, rural, poor, Indigenous women have often been subject to coercive and illegal medical practices in the name of the national interest.

From 1980 to 1992, Peru suffered a protracted internal armed conflict between guerrilla forces and the state. Because the main guerilla force, the Shining Path, was based in the southern Andes, Indigenous Andean peoples came to be seen as a threat by the Peruvian state. When elected in 1990, President Alberto Fujimori introduced a severe structural adjustment program and began setting the stage for a large-scale family planning campaign, purportedly to quell the violence of nonstate actors and set Peru on a new economic path.

In 1995, Fujimori launched the National Program for Reproductive Health and Family Planning (PNSRPF 1996–2000). The first president able to override the Catholic Church’s opposition to family planning, Fujimori’s program appeared to be a coup for women’s autonomy and reproductive rights. At the time, Peru’s maternal mortality rate was one of the highest in the world, and studies showed that upwards of 60 percent of women desired access to modern contraceptives.

But not all was as it appeared. By 1997, it was clear that the PNSRPF included government-set quotas for sterilizations. By 2001, over 314,000 people had been sterilized, 95 percent of whom were Indigenous women. Only 35 percent received full and informed consent prior to their tubal ligations, and women’s testimonies reveal that many were lied to, coerced, and captured to fulfill quotas.

Recent research reveals that the PNSRPF 1996–2000 was part of a neoliberal counterinsurgency plan sketched out by a military-civic junta in the 1989 Plan for a Government of National Reconstruction, also known as the Plan Verde, or Green Plan. The sterilizations allowed for a quick statistical drop in poverty rates to fulfill the terms of structural adjustment loans and, in the eyes of the military-civic junta, addressed the internal threat of a supposedly overpopulated and socially agitated Andes. The authors of the Plan Verde asserted that the Peruvian government “must discriminate…against these social sectors given their incorrigible character and lack of resource…the only thing left is their total extermination.”

In this context, the government saw Indigenous midwives as obstacles to Peru’s attempts to curb population size and maternal mortality. As Indigenous women were sterilized, midwives were persecuted. Quechua midwives not only tend to pregnant and birthing women but are also keepers of traditional plant medicines and serve as advisors to couples and families. Fujimori’s policies led many midwives to leave the trade or go into hiding.

After Vanessa sent me the RPP article, I spoke with urban midwives and lawyers in Peru. I learned that home birth is, in fact, legal; however, it is illegal for midwives to advertise or offer their services. Moreover, if the mother or child dies in childbirth, the midwife can be charged. Because of these restrictive laws and the extralegal persecution of midwives, Runa families have had limited access to trusted and traditional aid around contraception, birth, and family care, leaving Runa women and their families vulnerable to further reproductive violence.

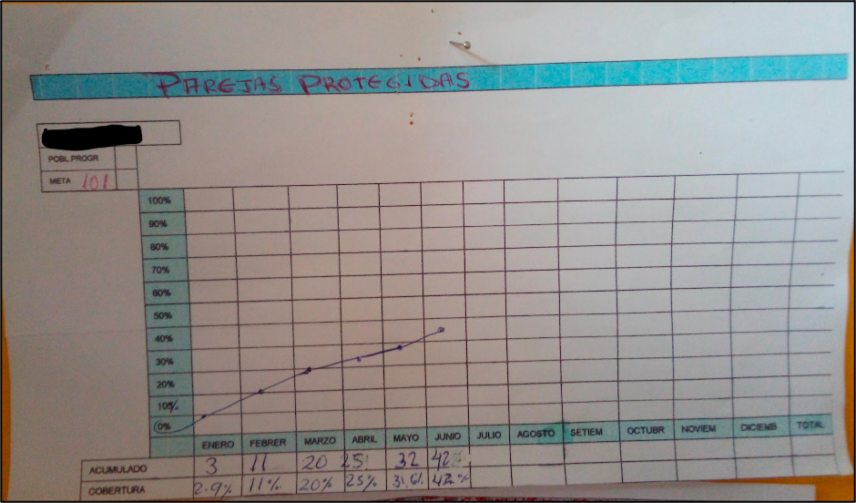

The medical post in the rural community in Cusco where I worked still advertises government-suggested goals for the number of couples to be protected by modern contraceptives.

Evidence shows these goals are not always met with free and informed consent. Imelda, whom I introduced earlier, was 19 when I met her. She recounted being harangued until she “consented” to receive the Depo shot after the birth of her son. “I hate the way it [Depo] makes me feel. I am always angry and get frustrated with myself [aburrida]! It affects my relationship with my husband. I don’t like it,” she told me one day as we sat in the sun playing with her baby.

Depo Provera is one of the least popular birth control methods in the United States because of its side effects. But it is cheap, long-lasting, and widely distributed among health posts in the so-called Third and Fourth Worlds. As a flyer in the health post in Imelda’s village states: “You can plan your family using the method recommended by health personnel that is available, free of charge, from the Ministry of Health” (emphasis added).

Imelda had given birth via cesarean section. In Peru, as in other parts of the world, almost 40 percent of deliveries are by C-section, though the World Health Organization indicates that only 10 percent of these are medically necessary. While perusing the Journal of Peruvian Gynecology and Obstetrics (Revista Peruana de Ginecología y Obstetricia), I came across a letter to the editor regarding the high rate of C-sections in Peru. The correspondents, a Peruvian doctor and researcher, noted that alongside other reasons, the high rate of cesarean sections in the countryside might be explained by the need to train “young doctors to develop this method of birth,” meaning that some of the “cesarean sections that are practiced are unnecessary.”

Though a standard procedure, the probability of dying from a cesarean is up to six times higher than from natural birth. And successful C-sections require four to six weeks of recovery. Because of the physically demanding nature of rural life, unnecessary C-sections expose women to the possibility of internal and external tears that can result in long-term disability or death. There are also other, culturally embodied consequences to the procedure.

When I met Imelda, her son was eight months old, but she still did not feel completely back to her pre-cesarean strength. I learned from Vanessa, the midwife, that even where the body heals properly, C-sections can have a lasting impact on a woman’s strength and vital energy (fuerza): “What does not heal [after the cesarean] is the connection of a woman’s energy field, and they lose their strength.” In Andean medicine, the seat of a woman’s vital energy is la madre, the womb. When this area of the body is harmed, the sequelae are not only physical but also psychospiritual and energetic.

In the past two decades, there have been notable advances in the field of intercultural health in Peru. For example, in 2005, the Ministry of Health adopted an intercultural birthing policy that made provisions for Indigenous birthing traditions, such as vertical birth and family presence, to be included in medical settings. Nonetheless, rural and Indigenous women still have to contend with the aftermath of state terror in Peru.

Rural and Indigenous women in Peru continue to face a medical system that subjects their bodies and social values to abuse based on racist, classist, and ethnocentric understandings of their decisions around reproduction and birth. Runa women’s preference for home birth is not due to ignorance but rather to an astute reading of the medical establishment’s disregard for their humanity and a desire to bring life into the world on their terms. Their decisions warrant protection.

María Lis Baiocchi and Leyla Savloff are contributing editors for the Association for Feminist Anthropology’s section column.