Article begins

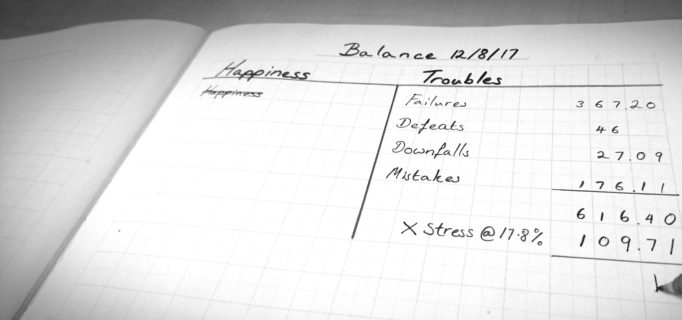

Anthropologists and their students spend a lot of time thinking about work. Our ideas about work intermingle with experiences we have in research, the classroom, and the lives we wish to lead. Here in the Bay Area, “move fast and break things” is pervasive, as is “fear is the disease, hustle is the antidote.” These slogans map onto the egregious wealth inequalities that drive our everyday anxieties and aspirations. These pressures to deliver and innovate in Silicon Valley echo the demands of higher education: We can take lessons from anthropology’s shifting approach to work in order to support the types of work and life in the Bay Area that we deserve.

Below, Maya Kaneko, a graduating senior and my research assistant, and I discuss the connections between studying anthropology and navigating work in Silicon Valley, a follow up to “The Conversation,” in which Ryan Anderson and I discussed how we mentor students about life and work post-graduation.

Maya—How can anthropology help me adapt to the tech industry’s ethics and expectations?

As an anthropology major, I’ve had the time to openly share my ideas and critiques about work. I read about women being held to higher standards than men, individuals being judged for what they wear or the color of their skin, and those on the margins not being duly credited for their contributions. I researched the rise of “workaholic” lifestyles—where it’s “cool” to always be busy, “hustle,” and love work. The household I grew up in revolved around my dad’s lifelong career in tech. His long hours, midnight work calls, and international trips normalized what this kind of work meant to me. I’ve always aspired to work in this industry. But now, as a woman of color, witnessing tech’s disruption narrative of “move fast and break things,” it’s difficult to see this workstyle as “normal” or just.

I foresee being caught off guard by the speed with which I’m expected to perform and deliver constantly. According to Jan English-Lueck, workers embody this new work style. As graduation approaches, I feel the need to optimize myself for work. Walking through stores, I notice overpriced products promising to give my brain a “boost” and provide my body with better sleep and energy, so that I can be even more productive.

Yet, work in Silicon Valley also feels strangely familiar. Corporate campuses use university models to make work all-encompassing: with gyms, free meals, laundry, and corporate perks on site, companies also supply nap pods so workers can give their bodies a break. But these breaks extend the time employees spend working. A peer of mine astutely observed that it’s as if we’re expected to live two competing lifestyles simultaneously: we ought to prioritize the absolutes of the wellness industry but are compelled to refuse our bodies’ signals and keep working no matter what. Both ways of life feed one another, forming a dangerous cycle. How can I remain critical and do meaningful work in these spaces? What survival strategies can anthropology give me?

Mythri—In Silicon Valley, you may have to move fast and break things. But you don’t need to break with anthropology. You also don’t need to break yourself.

The 4.2 trillion dollar global wellness industry is everywhere: University HR departments offer discounted faculty massages and meditation workshops. Our colleagues exercise, stand, and move only so they can gratifyingly watch the fitness tracking rings on their Apple Watches close. Everyone and everything screams: stay well to work and work to stay well. It is at once shaming and validating.

A closer look at anthropology’s own “wellness” crisis reveals similar cycles of depletion and reward. Stalls to support contingent faculty, failures to support BIPoC students, #metoo, and #hautalk demonstrate that our educational institutions are broken and will continue to harm marginalized individuals, unless those wielding power break their bad habits. Calls to break down anthropology’s toxicities are teaching us how to reorient what we should collectively accept as our field’s work ethics.

Anthropology has long demanded that its workers build upon the work of their ancestors. In theory classes, we train in a “narrow canon” sanitized to fit the ideals of empire and the ivory tower. Funding institutions demand outcomes that often extract from rather than center on marginalized communities. University donors and the pressure to cite, publish, and impact, structure the possibilities of our field, and the ways in which we access and engage ideas.

When I began graduate school in 2003, breaking these bad habits was unheard of. Fear fed the discipline. Hustle was a toxic coping mechanism. Those who publicly called out these wrongs were silenced, pushed out, and made illegible. Their work was erased—often by those doing the “innovating.” Move fast and break things, right?

Silicon Valley’s “breaking-ground ethic,” as Ryan Anderson and I recently argued, conflicts with calls to decolonize “everyday praxis/space” in anthropology and decanonize the field. As you enter Silicon Valley’s workforce, adopting these tactics can make your worlds of work more ethical: Build relationships with coworkers who remind you that the deliverables that “keep making magic” are the products of your labor. Demand that your work be recognized; when it is not, find ways to account for and record it yourself. Know you deserve to be right where you are even when others question your place and legitimacy. Note your path and privileges but also those who support and hold you up. Recognize that more voices are stronger and more effective. As Ashanté Reese reminds us, “commit to being whole”—your work is an asset even when supervisors, policies, and gatekeepers claim otherwise.

Most importantly, your history and the work you’ve done so far matters. As Kathi Weeks suggests, we need to release our expectations about what counts as a life, and we need to “get a life”: “It is not a call to embrace the life we have, the life that has been made for us—the life of a consumer or a worker . . . but the one that we might want” (Weeks 2011, 232). If the intertwining of work and life is inevitable, our desires to make our work more ethical are life endeavors that “demand alternatives” (Weeks 2011, 233).

An ethical reorientation to work is key to building just futures for anthropology and an antidote to long tolerated and rewarded toxic work practices. Learning from emergent and necessary voices in anthropology, workers in Silicon Valley can strive to break down the bad and embody these strategies of survival and solidarity.

Mythri Jegathesan is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at Santa Clara University and author of the forthcoming ethnography, Tea and Solidarity: Tamil Women and Work in Postwar Sri Lanka (University of Washington Press, June 2019).

Maya Kaneko is a graduating from Santa Clara University in June 2019 with a degree in Anthropology and Political Science. She plans on working in the Silicon Valley technology industry before attending graduate school in the future.

Cite as: Jegathesan, Mythri, and Maya Kaneko. 2019. “Work for a Life.” Anthropology News website, June 12, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1188