Article begins

“Hey Joe, instead of saying, No we can’t,” retorted Senator Kamala Harris to Vice-President Joe Biden. “Let’s say, Yes, we can.” With that single line, Harris resurrected an Obama-era sound bite on the stage in Houston during the September Democratic debate—a crowded stage with 10 candidates each seeking to get in a word edgewise.

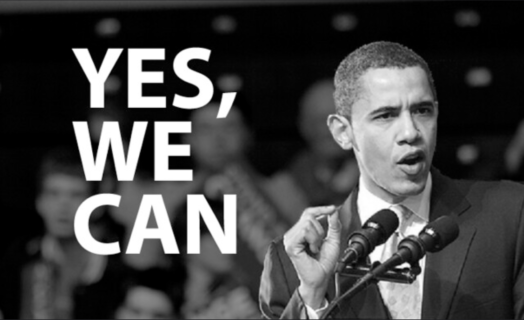

To rise above the fray and generate momentum among supporters, political campaigns have long relied on slogans such as Barack Obama’s “Yes, we can.” Much like Harris borrowed the slogan from Obama, Obama himself borrowed the words from Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta who used the Spanish version (“Si, se puede”) to mobilize the United Farm Workers in the 1970s.

But Harris’s use of the slogan on the debate stage in Houston didn’t have nearly the same impact it did in Obama’s stump speeches in 2008. Context and message resonance have as much to do with the effectiveness of slogans as do the poetic ring of the chosen words.

At the most basic level, political slogans must provide easily repeatable taglines for campaigns. But for political slogans to truly do valuable political work, they need to resonate with a candidate’s larger campaign message. This is what sets apart Obama’s “Yes, we can” from most of the current candidates’ slogans—including Harris’s use of that phrase in Houston.

The power of slogans relies not simply on their intrinsic aesthetic appeal—although that is a baseline requirement for their success—but also on a slogan’s intertextual resonance with historical usages and the campaign’s own central message.

The slogans being used by the current crop of Democratic candidates fall into a few different categories. The most mundane incorporate the candidate’s name into a straightforward tagline—for example, Beto for America, Cory 2020, John Delaney for President, Julián for the Future, Tulsi 2020, Yang 2020. More monikers than slogans, these descriptive taglines simply convey to voters that a particular person is running for office. The taglines don’t tap into the substance of the campaign itself or even hint at the reasons why the candidate is running.

The basic tagline can be spiced up with poetic devices such as alliteration—for example, Amy for American or Win with Warren. More creative yet are the puns, such as Feel the Bern, that play upon words that sound alike but have different meanings.

“Political slogans are designed to by witty, catchy, and most importantly, highly quotable,” carrying the campaign message far and wide (Hodges 2014). To those ends, a certain content bias—a term Nicholas Enfield (2008) uses to discuss a linguistic variant’s intrinsic properties—must be met to make a phrase memorable and repeatable. For a successful political slogan, this means a certain aesthetic appeal that arises from leveraging the poetic function of language.

More important than a slogan’s intrinsic appeal is the way it enters into specific contexts of situation, draws from previous contexts, and resonates with a candidate’s larger campaign theme. Obama’s “Yes, we can” slogan demonstrates all these elements.

Senator Obama first introduced this slogan in a speech to supporters on the evening of the New Hampshire primary in January 2008. In that speech, he tapped into the slogan’s rich intertextual history and connected that history to his own campaign’s focus on hope and change.

We know the battle ahead will be long. But always remember that no matter what obstacles stand in our way, nothing can stand in the way of the power of millions of voices calling for change.

[…]

For when we have faced down impossible odds, when we’ve been told we’re not ready, or that we shouldn’t try, or that we can’t, generations of Americans have responded with a simple creed that sums up the spirit of a people: Yes, we can. (applause)

Yes, We Can. cfishy/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Yes, we can. (crowd chants, “Yes we can”)

Yes, we can.

It was a creed written into the founding documents that declared the destiny of a nation: Yes, we can. (cheers)

It was whispered by slaves and abolitionists as they blazed a trail towards freedom through the darkest of nights: Yes, we can. (cheers)

It was sung by immigrants as they struck out from distant shores and pioneers who pushed westward against an unforgiving wilderness: Yes, we can. (crowd responds in unison, “Yes we can”)

It was the call of workers who organized, women who reached for the ballot, a president who chose the moon as our new frontier, and a king who took us to the mountaintop and pointed the way to the promised land: Yes, we can, to justice and equality. (applause and crowd chants, “Yes we can”)

Yes, we can, to opportunity and prosperity.

Yes, we can heal this nation.

Yes, we can repair this world.

Yes, we can.

Obama’s performance is marked with parallelism, repetition, and dramatic pauses, all elements that play a key role, as Richard Bauman and Charles Briggs (1990) explain, in “rendering discourse extractable.” Supporters in the crowd responded with their own chants of “Yes, we can,” illustrating how a text’s intrinsic appeal compels others to repeat it.

More importantly, Obama utters the slogan in the same breath as historical precedents of struggle and inspiration, alluding to the nation’s founding, the abolitionist and suffragette movements, and the struggle for equality epitomized by Martin Luther King Jr. The choice of the phrase itself—the English version of the United Farm Workers’ rallying cry for labor rights—further solidifies the slogan’s association with struggles for social change. That association, of course, is no coincidence; it closely paralleled Obama’s central campaign theme, codified in campaign materials through his other slogan, “Change we can believe in.”

The “Yes, we can” slogan therefore did valuable political work by indexing the larger message of Obama’s campaign each time the slogan was repeated in the intertextual web of public discourse. Prominent figures formed a powerful speech chain that propelled the slogan—and associated campaign message—into the public consciousness; musicians will.i.am and Jesse Dylan brought together several celebrities in a “Yes, we can” music video.

Obama’s use of “Yes, we can” illustrates the way slogans do political work. The power of slogans relies not simply on their intrinsic aesthetic appeal—although that is a baseline requirement for their success—but also on a slogan’s intertextual resonance with historical usages and the campaign’s own central message. Although Harris introduced a potentially compelling slogan of her own when she launched her campaign on Martin Luther King Jr. Day earlier this year (“For the People”), she and other candidates have yet to harness the musicality of language in a way that connects those words to a central message in the way Obama did with “Yes, we can.”

Adam Hodges is a linguistic anthropologist who writes about language and politics. His new book, When Words Trump Politics: Resisting a Hostile Regime of Language, is now available from Stanford University Press. His previous books include The ‘War on Terror’ Narrative and Discourses of War & Peace, and his articles have appeared in the American Anthropologist, Discourse & Society, Language & Communication, Language in Society, and the Journal of Linguistic Anthropology.

Cite as: Hodges, Adam. 2019. ““Yes, We Can” and the Power of Political Slogans.” Anthropology News website, October 21, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1291