Article begins

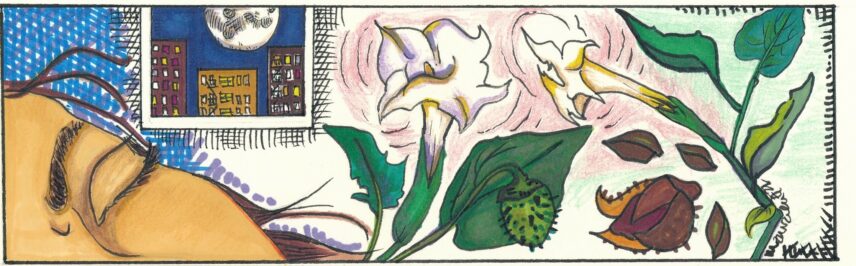

Death Angel, jimsonweed, downy thorn apple, horn of plenty, moon lily. The genus Datura, a member of the nightshade family, goes by many English common names and is distinguished by large trumpet-shaped flowers in colors ranging from white to blue and purple. Sometimes confused with angel’s trumpet (Brugmansia), a showy plant popular among gardeners for its colorful foliage and fragrant, downward-facing blooms (in contrast to Datura’s upward turn), the devil’s trumpet proliferates in open fields, ditches, and roadsides. In a neighborhood in Queens, geographically the largest and most diverse borough in New York City, this moon lily has made its home on the bustling urban streets.

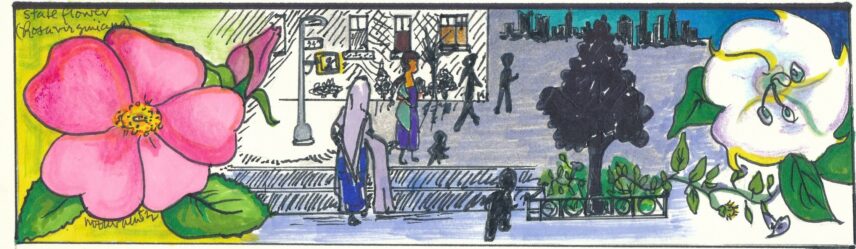

As climate patterns change and real estate development expands to accommodate ongoing population growth, the extinctions typical of expanding cities are now also paired with the proliferation of new species in novel landscapes. Insects buzz across their microhabitats at sundown and into the night, as predators pursue them across treetops, in the air, and on the ground. The city buzzes, too, with machines, traffic, people, and electric light. Nocturnal plants burst open, welcoming pollinators for late-night visits, primed for reproduction. City life and human neighbors engage with new plant varieties in transformed ecosystems. After all, what is a weed?

A common destination for those seeking new prospects and growth, New York also offers opportunities for foreign plants to successfully make a living in disturbed environments. Brownfield sites, vacant lots, and small patches of open soil all offer practical homes. And as the climate warms, tropical varieties begin to thrive farther north.

I first glimpsed the eye-catching devil’s trumpet in a small plant bed up the block from where I live. The shrubby plant quickly grew so large, it covered the potted plants growing beside it, concealing the nearby garden hose. I soon began to notice this unusual herbaceous bush, with its deep foliage highlighted by purple hues and large rough leaves, in other small garden plots beside buildings. It now flourishes in tree pits on the busiest boulevards in the neighborhood and envelops nearby traffic medians.

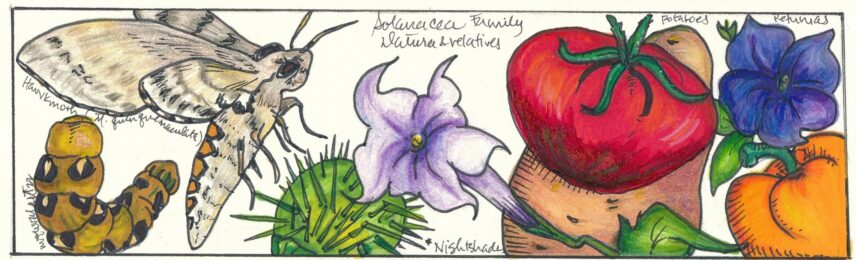

Every part of this plant is fragrant, not just its intoxicating flowers. The stems and leaves smell earthy and musty (sometimes even with a hint of what I can only liken to old cigarettes). City life can make it difficult to sense the full scent of flowers. But after dark, when the trumpets are in full flower, they emanate an intoxicating fragrance, luring insects to their blousy blooms, especially night-flying hawkmoths. With a long probiscis for probing the plant’s long nectar canals, hawkmoths are primary pollinators, transferring pollen from their furry heads to awaiting stigmas. Gardeners and scientists chatter online about whether moths become intoxicated by the plant’s potent alkaloids.

The geographic distribution of different varieties includes the southwestern United States, South America, and India. It thrives in direct sunlight and in drier climates. The origins of the aromatic species proliferating in Jackson Heights, Queens, could derive from anywhere, spreading tendrils amidst concrete and curb, among migrant communities old and new.

Mary Douglas’s conceptual work around matter out of place applies to such weedy species perceived as invasive and exotic. Urbanites’ tastes for bright flowers to break up limitless glass, steel, and concrete at least partly drives the introduction of flora from around the world. Other times, organisms find a way to travel far by alternative means, hitchhiking via container ship, wind, and unintentional human activity. Some city residents are beguiled by their exotic traits and cultivate them for their gardens. Others deem them dangerous either for their toxic properties, or for their specialized abilities to propagate wildly. Some city dwellers do not notice them at all, while others revile them for their weedy qualities and even their morphological features, like their thorny adaptations. Every part of the moon lily is toxic given its poisonous and hallucinogenic properties, spurring discussions on neighborhood online forums about safety, especially for pets.

Changes to climate patterns and habitats are generating games of chance when it comes to survival. The moon lily’s ability to proliferate might put it on par with other problematic species such as phragmites, mugwort, and other pioneer plant species colonizing deindustrialized lots across American cities. What kind of habitats enhance resiliency? This remains an open question. For now, the devil’s trumpet continues to thrive in this Queens neighborhood, coloring sidewalks and median strips, its aroma scenting the nighttime air.