Article begins

“You are too old to be a refugee.”

“You can’t stay in this country unless you serve four years in the military. And then when your kid is old enough, he has to serve four years too.”

“If you don’t have a police report that confirms what you’re telling me, you’re going to be deported. They’ll know you’re lying. You have to have proof to stay here.”

“You are a liar. You couldn’t have come this long of a way on your own. Not without a coyote. You’re telling me that you didn’t have a coyote? Then you must be a coyote yourself.”

“You are a liar. You don’t look like a r*pe victim.”

“The border is closed. Tell your families to stop coming here. We have a new president. Everyone will be deported.”

These are just some of the lies and accusations of deception told to asylum-seeking families by immigration officials in their first encounter at the Mexico-US border. As families recounted these experiences, often through exhaustion and tears, legal advocates, including myself, sat, listened, and recorded. Then, working with the families, we corrected those lies and refuted those accusations repeatedly. This wasn’t the reason we were meeting where and when we did—in a detention center for families—but it became a necessary part of our work, as much as anything else. Indeed, deception plays an important role in the story here, too.

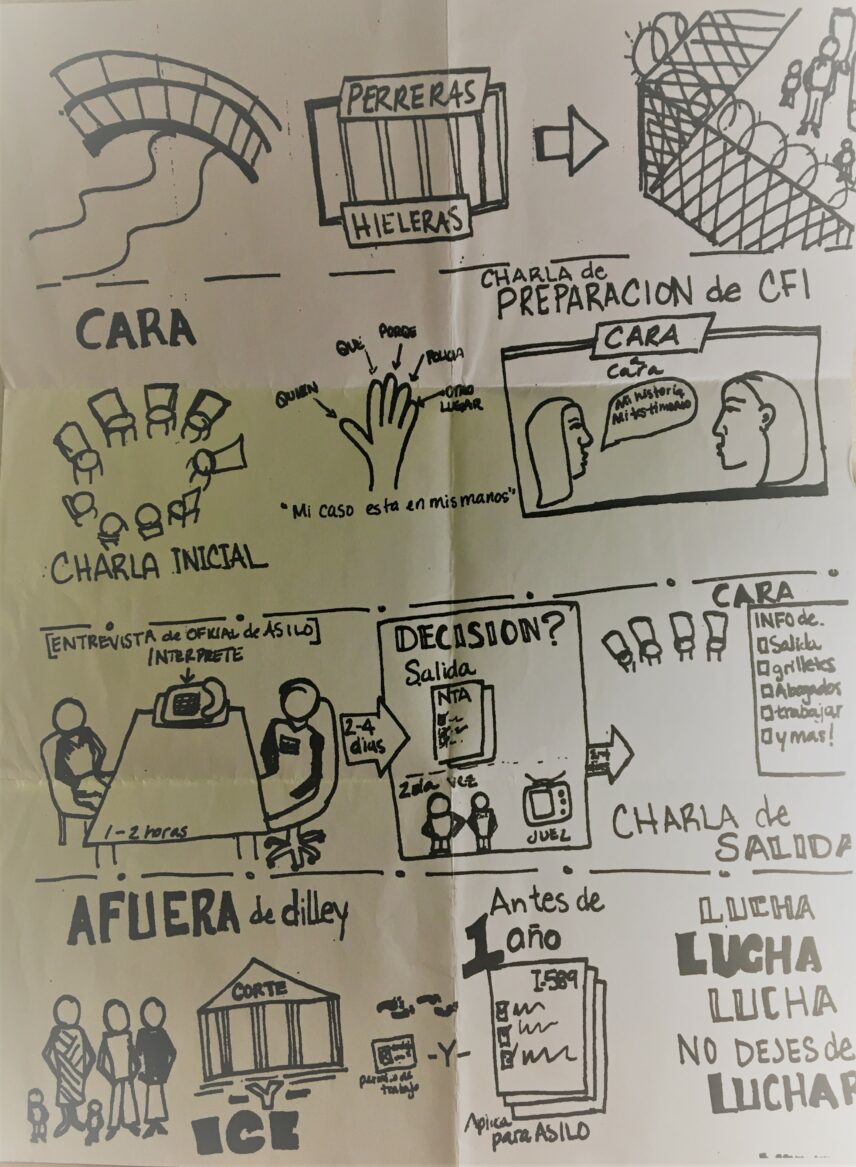

The story begins in Dilley, a small country town in South Texas. In 2015, amid rising arrivals of asylum-seeking families along the Mexico-US border, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) constructed and opened a facility in Dilley intended to detain some of those families while they underwent one of the initial stages of the legal process: the credible or reasonable fear interview. Thus, after requesting asylum and being selected for placement within an expedited legal category, a single parent and their minor-age children were transferred from an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) holding facility to one of these centers. In order to be released, continuing with their application, they would have to “pass” this interview with an asylum officer. If deemed not “credible” or eligible for asylum, they were subject to immediate deportation.

Around the opening of this facility, a coalition of national legal nonprofits formed to provide continuous pro bono legal assistance to those detained, relying heavily on volunteer labor. Like many immigrant rights groups at the time, these advocates were deeply disturbed by the practice of incarcerating asylum-seekers, especially children, and recognized the need to mobilize legal aid for those detained in what was the largest immigrant detention facility in the United States. They did this work for several years, across multiple presidential administrations and substantial fluctuations in asylum policies. Only within the last couple of years did the practice of family detention, in this specific form, cease.

I have written previously about the efforts and perspectives of these legal advocates, including how they experienced trauma in their work and how it, effectively, constituted a form of care labor, which I call “legal care.” The most important role these advocates played in this facility was, arguably, that of a kind of story translator: in helping detained families understand complex legal processes and communicate the experiences that qualified them for asylum, they ultimately helped them to pass their interviews and get released, rather than deported. Their work wasn’t about long-term representation; it was about climbing over this first hurdle. Their labor was deeply meaningful, careful, and yet also painful.

Here I explore something that is pervasively associated with asylum-seekers or migration in general in the public imagination: deception. It is still common to hear the refrain that asylum-seekers intentionally lie about their life circumstances in order to be given asylum, designated as “bogus,” or fraudulent, cases. This attitude filtered into how immigration officers often approached interviews, as I both witnessed and learned from numerous asylum seekers and advocates. Such associations, of course, are often spurred by—and subsequently reinforce—xenophobic beliefs and attitudes toward different migrant groups, rather than through any sort of grounded reality or broad awareness of either international issues or acceptable legal categories for applicants. However, this story is about neither this harmful association nor the simple fact that, of course, legal fabrication exists. Instead, I acknowledge and explore deception’s integral place in such a space, but not in the way you might think. Deception, in truth, is a prominent feature of both the material conditions of this form of detention and the entwined relationships therein.

A Front

Here, on a barren, dusty plot of land, lies four walls, two doors, several spare office spaces, a long, windowless middle space, and one special little room for coloring books, cheap plastic toys, and miniature chairs. It’s in this space—a mobile trailer converted into an office—that volunteer legal advocates met with the asylum-seeking mothers and children that were held there. Beyond this are many other temporary structures of similar size and feel, connected through raised metal walkways or beige concrete paths. Still other spaces exist in this sort of compound, surrounded by multistoried, locked fences, cameras, and rows of floodlights that remain on throughout the night.

Near the entrance—which is effectively hidden from public view by a long, unmarked road that vanishes into a wide blue sky—you’ll find a sign that’s meant to tell you what it is: the South Texas Family Residential Center. On the same sign, you’ll find the letters “CCA,” referring to the former Corrections Corporation of America. This business, now known as CoreCivic, is one of the nation’s largest and most lucrative private prison corporations. They own and operate this facility, and many other detention centers, through highly profitable contracts with ICE.

Side-by-side, these denotations would seem to have very different connotations. What is this place, and what is it for? Really, it depended on who you asked. Inside this collection of edifices—which legal advocates call a “baby jail”—you’d find further evidence of what appeared to be a very conflicted sense of functional identity. You’d see and hear evidence that suggested this place is of a noncarceral nature, with detainee dormitory units identified by a color and creature (such as “blue butterfly”). You’d quickly be made aware of the strict controls and limitations on movement within, while also being coerced into referring to staff not as guards but as “residential supervisors.” Promotional materials for the center touted the “amenities” for “residents,” like childcare or Zumba classes, while legal advocates and nondetained family members were repeatedly denied access to meet with those detained.

The misidentification of this place as primarily one for those to simply “reside” had real effects. Beyond the most obvious—misleading both detainees and an underinformed public about their function and profit incentive—the legal advocates’ work was impacted by this confusion. Advocates’ efforts were, in so many ways, predicated on their ability to establish trust with detainees, which they needed in order to get to the kinds of vulnerable, frank conversations necessary to help prepare their legal cases. But how does one conjure a sense of trust within such a deceptive space? Molly, a legal advocate and experienced immigration attorney from Colorado, shared how even when, under normal circumstances, you are good at establishing that kind of relationship with a “client,” this “weird, artificial prison” changes things: “I mean, I think it would be my natural instinct not to trust anybody in that environment,” she said.

Molly wasn’t wrong; the nature of the environment, a space of conflicting architecture and identities, informed this sense of unease, a sense that you might not be able to trust whatever stood in front of you. Was it there to give a moment of respite for asylum-seekers or punish them for even making the journey? This second point was only reinforced by comments from the previous secretary of homeland security, Jeh Johnson, who, at the opening of the facility, described it as a “message to illegal migrants.” Of course, asylum-seekers are just that—people who are exercising a legal right to seek asylum—just as the families were that were being detained at this center.

Further, this unease, a sense of being caught in-between, was infused in the very architecture. Nearly all of the center’s structures were, and continue to be, temporary—mobile trailers that made more sense in the context of, say, underfunded crisis response. The makeshift conditions of the spaces evoked a feeling that, like a traveling circus, you might just show up one day to an empty field, having no idea what happened to the “residents” within. This mirrored the experience of laboring as a legal advocate upon the ever-shifting terrain of exclusionary migration policies and practices. The environment mattered, what it looked and felt like, and legal advocates fought to affirm this sense for those they helped. Every day, in order to move forward—in building that trust, demonstrating that they were there to help, that they wanted to get folks free—advocates had to start somewhere. Because the unstable material nature of the center muddied everyone’s sense of reality, building those sorts of relationships took more work and, consequently, a unique toll.

Working the Frame

When legal advocates met folks in family detention, they worked to prepare them for their asylum interview. They listened and asked questions about why a particular individual was seeking asylum, but in a different way than an asylum officer. As a detainee began their story, the advocate was listening and following up with an awareness of acceptable legal categories for asylum, with an eye (or ear) toward the details that require either highlighting or fleshing out for greater effect when the time for their interview came. The work in that preparatory meeting was to take all the little pieces—the subtle and not-so-subtle nuances, the histories, even the apparent gaps—of an applicant’s self-narration of their life and help shape it into terms intelligible for the limited allowances of asylum law. From one standpoint, such work makes complete, reasonable sense; from another, it opened them up to a serious charge.

On multiple occasions, advocates were accused of encouraging detainees to lie in their interviews, either to wholly fabricate claims or to repeat legal terms and concepts simply to pass that interview, whether or not they actually applied to an individual’s case. Sometimes this was a direct accusation from asylum officers suspicious of legal advocates’ work and motivations. I experienced this myself as an advocate who attended many interviews in support of the women I had helped prepare. Other times, it was more of a kind of gossip that circulated among other skeptical administrators and staff of the facility. Some asylum officers chose to characterize what legal advocates did in preparing detainees for their interviews as “coaching,” which, in their pejorative framing, was deceitful.

In truth, this is a curious charge, particularly when it comes to the interview stage of the asylum process. In the interview, detainees were called upon to tell a story that covered both their individual experiences that led them to flee their homelands and their subsequent need to be given protection through asylum. Rather than simply telling a story of one’s life, detainees often needed both information around this and preparation. Understanding how to navigate complex legal processes, like asylum, is like learning a game. Joe, a retired attorney from Austin who frequently volunteered in family detention, coincidentally used this coaching analogy to describe the necessity of their work: “The interview is like a basketball game, and [our preparations with them] are like practice,” he said. “You can’t go out onto the court without knowing the rules of the game first.” While not a game, legal processes, like this interview, have rules, expectations, allowances—a language all their own. The work that legal advocates undertook served to make all this comprehensible for applicants, and consequently, to help them maneuver this translation, effectively on their own, as advocates could not “represent” or speak for them during the interview.

It’s odd, disorienting even, to suggest that advocates’ preparatory work impedes the “truth-telling” exercise that is an asylum interview. Such a claim implies that a person telling a story doesn’t need to know what matters to the person listening: that the truth simply issues forth on its own. But this idea relies on some concerning assumptions, not least of which is that this is, in fact, an opportunity for a person to tell their story on their own terms. The problem, of course, is this isn’t how an asylum interview operates. It’s a back-and-forth, an exchange of questions and answers, a moment that often calls for self-advocacy (for which an applicant would need to recognize themselves). If a relevant question isn’t asked, a point not followed up on, an applicant might miss that moment to share those parts of their story that mean something to this process. If not or improperly prepared for that moment, it could pass unnoticed, in an instant, changing the direction of their lives yet again. How an asylum-seeker’s story was told, how it was translated to a potentially skeptical or disinterested listener, mattered. Such is true of any story, one might argue, but in this case, the outcome could mean life or death.

A False End

Knowing where to start or end a story, even if it is your own, is not as straightforward as it sounds. If a single, life-altering event happens to you, beginning and concluding that tale might be easier. But what if the alteration of your life happened in pieces, at different times, maybe without a clear connection? Do you think about your life as a linear, progressive sequence of events, and if pressed, could you talk about it in a way that convinces a complete stranger that you’re telling the truth? Telling a compelling, convincing story isn’t just about what matters or means something to you. It’s also about knowing what matters to your listener (or reader). Knowing what matters and convincingly narrating that to your audience isn’t a question of whether you’re telling the truth; in some cases, the truth is beside the point. The point is about you and thus your story’s proximity to something reliable, intelligible to others.

Trying to do so under duress, like following a traumatic journey or while incarcerated, only compounds the challenge. Sometimes, especially when everything is on the line, people need help getting there, and for that matter, staying.

When asylum-seeking parents and children first met with legal advocates in a little mobile trailer in Dilley, they told varied yet familiar stories of that first encounter with ICE and CBP officers. Those stories were often marked by trauma and confusion: untranslated paperwork that must be signed; family members’ forcefully, and at times violently, separated from one another; and, as shown at the top of this article, the repeated use of degrading and offensive remarks. But those experiences were also marked by clear expressions of deception, sometimes in the form of blatant fabrications and other times as misleading mistruths. Legal advocates in family detention played a critical role in countering these lies. Deceptive immigration practices, of course, don’t end there, but are deeply entangled with US migrant detention on a grander scale.

What those advocates also effected, though, was a counternarrative, or alternative story: one that challenged false narratives of deceptive asylum-seekers caught in ambiguous “residency.” All of this highlighted the irony of charges of deceit leveled against both. In their narration, these families were being punished through incarceration and a harsh expedited legal process for simply exercising their right to seek asylum, and this country’s influential private prison industry benefitted immensely from such a turn of political events. Even still, as the practice of family detention eventually ended, it was replaced with a wave of new and some would argue crueler forms of exclusion for asylum-seekers. This, unfortunately, has upended much of our collective sense of any individual’s legal right to seek protection through asylum, particularly when framed as something inherently exceptional. Facing an uncertain future, one might begin to wonder if there was ever a reliable story to begin with. Surprisingly, even in detention, it can be easy to lose your sense of direction.