Article begins

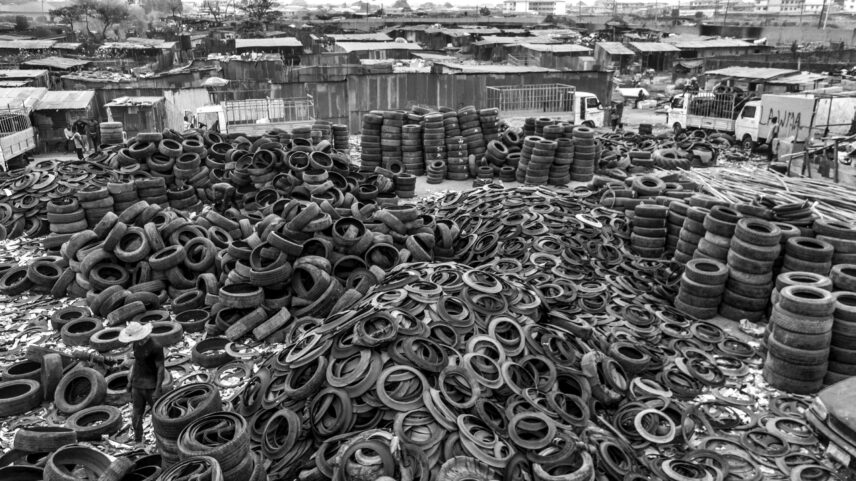

End-of-Life tires (ELTs) are virtually ubiquitous in the streets of Lagos. They lie abandoned by the sides of roads and the banks of waterways or stockpiled in dumpsites away from the smarter suburbs. Nonbiodegradable, their resilience allows them to cling to the urban fabric before becoming breeding grounds for malarial mosquitos or fuel for smoke-laden fires. But a tire that has apparently reached the end of its useful existence may also be revived to take on new social and infrastructural life. As one Lagos resident told us, “In Nigeria, a tire never dies.” What seems like inert trash might actually be matter on the cusp of transformation, about to cross the fluid boundary between waste and well-being, refuse and resource.

Our British Academy-funded project Pneuma-city explores the numerous pathways that tires trace through the economy and ecology of Lagos—a city of around 20 million people that hosts some two million vehicles on its roads every day. Once detached from cars, buses, and lorries, tires may retain their shape but change their function, deployed as platforms for portable generators, stands for the display of market goods, or informal means of marking out space on road or beach. They may even be upcycled, re-formed into distinctive items of furniture or works of art that are encountered in galleries rather than gutters. In February 2022, Jumoke Olowookere, alias Jumoke OlowoWaste, opened Nigeria’s and possibly Africa’s first Waste Museum in the city of Ibadan. Transmogrified tires play a starring role in the museum’s depiction of the conversion of trash into tourist attraction, global commodity into unique object.

Tires may also take another turn in the circulating economy of the city, becoming ground into “crumbs” that—in a curious twist of fate—are used to produce the very asphalt roads along which the tires initially traveled. Or they may be carted away and burned—this time not in impromptu fires but as part of an industrial process changing tires into fuel, for instance providing energy for the Nigerian branch of multinational cement company Lafarge.

As part of our project we are investigating the lives of those human figures who play a key role in prolonging a tire’s life or pronouncing its demise: the “vulcanizers” who labor by the sides of roads to inflate or repair tires, to restore and retread them, perhaps to take a tire that is tokunbo (secondhand/foreign-used), before determining that it can indeed be resold to ply the roads once more. As one vulcanizing “master” told us, to complete the necessary training a person needs both “a discipline and a dream.” Another claimed to be able to identify a tire—Dunlop, Michelin—by its smell, as if he were a connoisseur of rubber.

“We seal air” as one vulcanizer put it. But vulcanizing has its dangers, since an over-inflated tire that suddenly bursts can blind or maim. The trade also lies at the center of a deeply contested project of urban governance: the ongoing attempt to create not only a mobile but also a modern, ordered, “clean” Lagos. During sanitation days, mandated every three months, vulcanizers are required to clear the streets of abandoned tires, and those who shirk their duty can be sanctioned by the vulcanizer’s police (made up of peers who maintain professional standards and order). Vulcanizers’ values are expressed in a standard exchange between workers that signals both belonging and aspiration. In response to the greeting “LSVA” (which stands for Lagos State Vulcanizers’ Association) the expected reply is a single word: “Progress!”