Article begins

Matt Sakakeeny: It was your idea that we talk about how collaboration structures each of our work. The unexpected possibilities for expansive communication in academic writing, but also in sound recordings, documentaries, radio, or public conversations. What would you say to an anthropology audience about the possibilities of collaboration in both creative sound production and academic publishing?

Steven Feld: Combining theory through storytelling, research as composition, and media production is what I did in my Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra project, a book with five films, 10 CDs, and photographic work. The text writes through conversation, through listening and voice, as a way to explore acoustemology—sound as a way of knowing. But the text and images also refer to the CDs and videos. So that’s an example of intermedial work in 15 years of collaborations with musicians and artists in Accra.

MS: You’re really drawn toward layering: thick sonic textures appear throughout Sound and Sentiment and the work you’ve done in Papua New Guinea from the seventies to the present. And then in the Accra book your writing is a Bakhtinian polyphony of voices. There’s a kind of grounded theory that’s going on between the sound world you’re writing about and the interwoven words of your collaborators, yourself, and the theorists you’re citing.

SF: The Accra book opens with Bakhtin: “The artistic will to polyphony is the will to the event.” And that’s why the first chapter starts with musician Nii Noi Nortey saying to me, “Where are you from?” And why it ends with footnotes written dialogically, from what I read back to my collaborators.

So, on one side of the recording booth, a musician has just gifted me a window into his musical mind, into how he can hear 10 other simultaneous tracks when he plays solo guitar.

MS: Something you modeled for me is how to balance the disciplining and objectifying that is expected of us as scholars in the academy, with experimental and creative worlds that are happily more unruly. You stage different collaborations for different formats—texts and sound recordings and video documentaries—but they each begin and end in collaborative dialogue.

SF: Example. In Accra I work regularly with multi-instrumentalist Nii Otoo Annan. He taught me rhythmic principles and I went on to perform and record with him in Accra and around the world. One afternoon, we recorded 13 of his songs for solo electric guitar. Ten months later he came for an artist residency at the University of New Mexico. And over a beer one night, he said, “If we go to the studio I’ll show you what’s inside the guitar songs.”

So, we went to the studio with a carload of instruments he chose. As I played the first song back to him, he overdubbed a bell part. Then he listened to the guitar and bell and recorded another bell part. And then a third one. And then a rattle part. And then a drum part, and then an electric bass part. And we ended up doing this for all 13 songs, 10 of which also had vocal parts that he sang. And then, with a laugh, he said, “Ok prof, you know the music, make the arrangements!”

So, on one side of the recording booth, a musician has just gifted me a window into his musical mind, into how he can hear 10 other simultaneous tracks when he plays solo guitar. And on the other side of the booth, looking at the Pro Tools screen, a musician has just gifted me a challenge to experiment mixes with how the parts fit together. And then to play them back for him, to begin another round of dialogic editing.

The Ghana Sea Blues CD is both a work of collaboration and research. It explores musical thought, and is presented in a format that brings income and recognition to an artist. And it’s a conversation that invites others. You’re a guitarist Matt; so when you listen you might ask, “How’s he doing that”? And you’ll get your instrument to work it out. There begins yet another conversation, and with it, another listening to histories of listening.

MS: I took your work in the Bosavi rainforest as a call for participatory sound making as a way of being in the world and making sense of the world, and the response was my first essay about musical processions, “‘Under the Bridge’: An Orientation to Soundscapes in New Orleans.” Your work in Accra hadn’t appeared yet, so I wondered how a theory grounded in a context of profound multinaturalism and cooperative egalitarianism could be reconfigured for people navigating an urban environment and a stratified political structure. You literally called me when that piece came out and we’ve kept the conversation going over the years.

I saw how academic writing could be one among a fleet of activities that circulate outside the ivory tower and open up wholly different possibilities of conversation.

Through those conversations—and your essay on dialogic editing and the practice of dialogic auditing you used to make the CD Voices of the Rainforest—you’ve modeled for me how to go about creating collaboration. I saw how I could write a book that didn’t claim to represent the experiences of Black musicians but was instead organized around ideas that were important to them, their knowledge that could never be fully knowable to me but that they directed me toward through conversation. Like you said about Jazz Cosmopolitanism, I saw myself as a listener to and an orchestrator of a polyphony of voices. The words of Roll With It! were paired with images by New Orleans artist Willie Birch, and we wrote an epilogue together. The book became about the collaborations that went into making the book.

SF: Your deep background working in the public media sphere and then coming into academic practice is foundational for these new collaborative imaginaries. Not just your fieldwork and the way you write it, but also the different ways of mediating it, producing it, promoting it to connect with community practitioners and activists.

MS: I grew up playing in bands and studied sound engineering in college. Bricolage wasn’t a theory to me; it was a practice. I made bricolage by recording sounds—interviews, narration, music, sound effects—and then layering them together. I worked as an engineer at the Smithsonian and as a producer in public radio into my thirties. Working in sound taught me how to make stuff through collaboration and working in radio taught me to imagine an audience and communicate with them through speech and other sounds. Transitioning into academia, the idea that you write a dissertation for your dissertation committee or a book for your tenure committee was totally anathema to me.

Your work helped me see through that conundrum too. Listening to Voices of the Rainforest and especially the recordings you’d started making in Accra and watching these wonderful films. I saw how academic writing could be one among a fleet of activities that circulate outside the ivory tower and open up wholly different possibilities of conversation. Public programming of art exhibitions, presentations with my collaborators, making stories for NPR where you hear their voices and you hear their music. And I’m incredibly lucky that I get to live in the place where I do my research. I was hired into a traditional music department but we set about recruiting some incredible scholars, composers, and performers in Black American music and Latin American music. I invite New Orleans musicians into the classroom. And pay them. And I have this incredible luxury of going off campus and organizing different kinds of collaborations that aren’t just solo-authored works. Like I volunteer with Derrick Tabb, one of the musicians from the book, at his afterschool program for kids called The Roots of Music. You and I haven’t been in direct dialogue with one another over the course of all of this, but when I read your essay on dialogic editing or watch your film on honk horn processions in Ghana I’m recognizing an affinity for what I’m doing where I live and work. It’s opening up a space for sanctioning that.

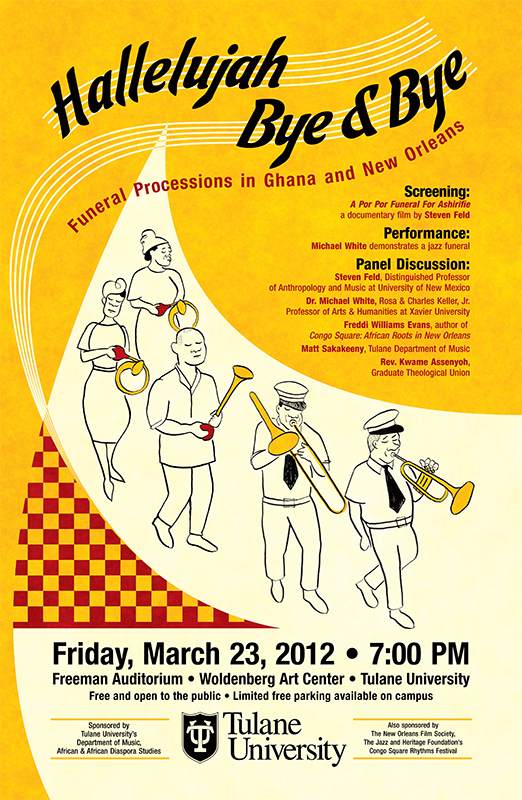

SF: When we embrace these conversations about shifting worlds it allows us to reach far beyond a singular authoritative statement about something. That’s why it is so necessary to promote collaboration as a scholarly ethic and personal imperative, up against a system that promotes hierarchy and systematic inequities. That was what was so powerful about your invitation to show A Por Por Funeral for Ashirifie in New Orleans for an audience that lives with the presence and memorial work done by jazz funerals.

MS: When you presented that film, about the honk horn musical funerals in Accra, we couldn’t presume there would be a resonance with the local experts on musical funeral processions in New Orleans, Michael White and Freddi Williams Evans. But I wanted to lay the groundwork for that to happen, right? For the hope that a transatlantic conversation could take off between African and Black American communities both drawing upon deep roots, but also transforming tradition.

SF: At the end of the film, photographer Nii Yemo Nunu sits with Por Por bandleader Nii Ashai, to look at Leo Touchet’s Rejoice When You Die: The New Orleans Jazz Funerals. And Nii Yemo says, “This is amazing. They’ve been gone for 500 years and they still practice some of the tradition.” That’s a mythologization from an African voice that could equally come from an African American voice. So the conversation needs to acknowledge that the New Orleans brass band funeral procession and the por por honk horn funeral processions are historically unique. At the same time, it needs to acknowledge that they share equally in practices of resounding memory in public parades. Whatever the historical differences, there’s acknowledgment and pride from each direction.

There’s a moment when Nii Yemo is looking at Rejoice When You Die and says, “Looks like people we know around here.” And at the New Orleans screening, following the film, somebody in the audience responded, “Man, it looks like people we know around here!” That’s when it seemed to me that you managed to stage a moment of recognition, a point of connection, voicing reputation, voicing memory. Collaboration as conversation and vice-versa.

MS: And to be part of a community, like you are in Accra or I am here in New Orleans. Today scholars are talking about decolonization, Indigenous forms of knowledge, standpoint epistemology, and the politics of representation and recognition as potentially transformative. Some have said that white men should step back from these conversations. Something I learned through your work is that it’s possible to have a conversation as a productive intervention. Of course, not everyone should participate in every conversation, but I think we all need to step up with the considered offerings we can bring. Reproducing colonial practices of extraction and misrepresentation and ownership does not have to be inherent to us staging or joining a conversation.

For that particular event it was a question of me looking at your por por film and saying, “People I know and care about need to know about this. And I can introduce it to them, and the filmmaker can come and he can learn something from a conversation with them.” There’s potential for radical humanism through mutual recognition, and I think we need to join in from wherever we’re at, even with something as modest as an event where there’s an exchange of ideas like we’re talking about.