Article begins

Long-term residents’ experiences of technological disruption and resilience are an untold yet essential part of the Silicon Valley story.

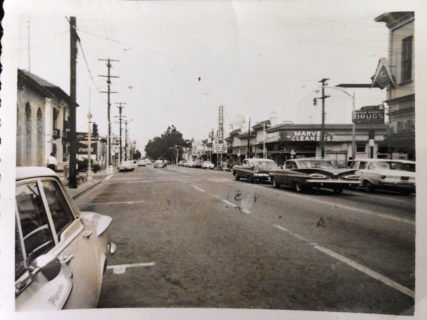

Franklin and Main Street, 1963. Tom’s personal family collection

In May 2018, I spoke with Tom, an elderly man who has lived in the same house near Franklin Square in Santa Clara since the age of five. Now in his eighties and with limited mobility from a surgery targeting a brain tumor, he spends his days on the couch with a view of the park he played in as a child through his front window. We spend a day opposite one another in his living room, joking about our opposing views on baseball, his suggestions regarding my career path, and his age and physical state. Periodically, he launches into tangential stories of his childhood in Santa Clara—tales about racing back to the park with his brother and friends to reenact battle scenes from films they had just seen at the local movie theater or gathering for holidays at his grandparents’ house just around the corner. I learn about Mr. Gravely, who watched over the park, and the old bandstand that Tom and his brother would climb on while their mother shouted warnings from the window. The park he looks at now is different from the one he played in as a child. The bandstand was removed and relocated, then replaced with a large white gazebo and concrete tables. It remains empty except for the occasional homeless person taking shelter or seeking a place to sleep.

Tom has lived in the heart of the Silicon Valley since well before the region received its moniker in the 1970s, before the arrival of the tech industry and the building of Googleplex and Apple Park. In the midst of the area’s radical changes, Tom and other long-term residents struggle to hold onto their sense of home as derived from their emotional attachments to their physical surroundings. The prevailing narrative of growth emerging from both local and national media ignores the stories of established Bay Area residents. Each individual has a unique and intimate connection with the area that is threatened by technological disruptions and real estate developments. Their experiences of displacement, psychological trauma, and residual healing often go unnoticed, but they are an integral part of the Bay Area technology boom. As Silicon Valley rapidly expands, the community is becoming increasingly more centered around corporations and the tech industry, rather than human connection. According to the Silicon Valley Institute for Regional Studies, the population has increased by 161 percent since 1960, breaking 3 million in 2015 (Hannock 2015). In this context of seemingly endless development, personal narratives and a sense of home are erased along with a lost history of the town of Santa Clara. Delving into these stories buried beneath technology headlines and new start-ups, unearths a different side of the Silicon Valley.

A lost community

Each time I ask Santa Clara natives about the meaning of home, I am told nostalgic stories of a historic downtown, which centers around the intersection of Franklin and Main Street, a junction that no longer exists. Reminiscing about the local atmosphere, one community member explained that the Franklin Street area “provided the city with spirit and life.” To walk down the streets of historic Santa Clara was to engage in friendly conversations with shop owners who were also neighbors and friends. The movie theater, city hall, and the local church were surrounded by family-run businesses that lined Franklin Street, creating a community based on proximity and familiarity.

As the physical area of Santa Clara transformed, the closely allied affective landscape changed with it.

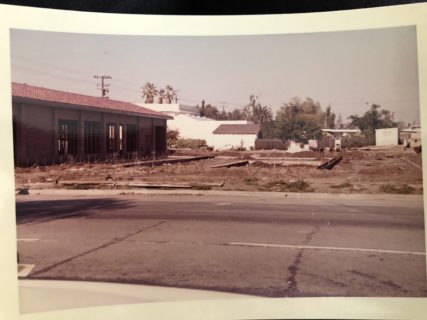

As the physical area of Santa Clara transformed, the closely allied affective landscape changed with it. Newcomers in pursuit of careers in an attractive tech industry threatened and ignored the connections that people had with the area—relationships that had been cultivated over many childhoods and years of inhabitance. My conversations with residents about post-urban renewal culture exposed an enormous sense of loss and shame. While teling me his memories in the park, Tom explained sentimentally that “back then it was a simple life.” A lead member of a local reclamation group, now in her sixties, was nearly driven to tears when telling me about her experience returning home after the failed Franklin Facelift Plan. Each person spoke of memories in spaces now occupied by quiet strip malls and corporate offices. Using terms like “destroyed,” “scared,” and “crooked,” they described the layer of embarrassment that fell over the community after their own government stripped them of a downtown that had provided so many community members with livelihoods and senses of identity. The community they grew up in, with its relations, social interaction, and familiarity, now sits in the periphery of the tech industry. The change became a taboo topic of conversation, too difficult for most to confront or acknowledge, and the erasure of the physical downtown and personal histories eventually fell into the shadows of the ever-expanding tech industry.

Disruption breeds resilience

Silicon Valley is experiencing what Richard Walker refers to in his book Pictures of a Gone City as “New Urbanism”: a remaking of a city through which “greater density, commercial revival, cosmopolitan pleasures” are acquired (2018, 153). The growth and prosperity of such urban remodeling are rarely equally distributed; loss invariably accompanies expansion. Those who have access to growth in Silicon Valley—large tech companies and their employees—reap the benefits: higher salaries and campus amenities like free food and fitness classes as well as access to the latest tech products. Those who are not involved in the industry—long-term residents and older people—are subject to technological disruption. Community development plans are buried and emotional ties are erased as technological advancement takes priority over personal histories. This New Urbanism and its growth ethic promote capitalistic objectives while minimizing opportunities for those who remain on the periphery of the industry.

Franklin and Main Street, post-urban renewal, 1965. Tom’s personal family collection.

As the newly defined community of Silicon Valley continues to prosper, those who have been left behind nevertheless move forward. Members of a reclamation group tell me about their initial meetings and conversations, describing the relief they felt in finding others who shared their pain and in opening up after years of keeping quiet. Attending their meetings, I hear about the change in attitude and growth they have seen over the years, as the group helps long-term residents begin to speak out about the losses they have suffered. Engaged in ongoing conversations with the city of Santa Clara, they strive to recreate this community by restoring the central downtown area with the old movie theater and family- owned businesses that previously lined Franklin and Main Streets. Despite the fact that community members are still mourning the loss of their childhood downtown, they exude an aura of acceptance and hope. Most have come to accept that the downtown Santa Clara that holds their memories of childhood no longer exists and that the demographic of the area is changing dramatically. This acceptance provides opportunity to plan for the future and work passionately towards restoring a community atmosphere that can be shared with old and new residents. Through local activism, members aim to rebuild the purpose, identity, and spirit that disappeared with historic downtown Santa Clara.

Franklin and Main Street, present. Emi Caprio

While most of my research examines the damaging effects associated with technological disruption, I have also witnessed how community members are coping with these disruptions. The unequal impacts of the growing tech industry and wealth accumulation make Silicon Valley an ideal breeding ground for what Catherine Fennel (2015) describes in her discussion of cultivating resilience, as strength born from a disadvantaged situation. In the void left by the expanding tech industry and the dissolution of their downtown, residents work to overcome the disturbances and transformations to their lives, to survive and carry on.

My day with Tom concluded with sifting through old photographs of places deeply ingrained in his childhood memories of Santa Clara, yet unfamiliar to me as a university student and young resident. A story accompanies each photo: the church with the crazy pastor who shot birds, his father’s barber shop on Franklin Street, the field where he grew up playing baseball. Although the physical locations in the photographs and the associated individuals are gone, Tom keeps them alive on the walls of his home. His living room overflows with hand-drawn scenes from his childhood. As the ink fades, he recolors them to keep the images vibrant. There are intricate pieces depicting his late mother, Tom and his dog in their front yard, and his friends and Mr. Gravely in the park across the street. His pastime maintains his motor skills and keeps his mind sharp while recreating his memories of a Santa Clara that has disappeared beneath the tech industry.

Emi Caprio is a fourth-year anthropology and psychology double major at Santa Clara University. She has previously conducted anthropological research in Costa Rica and Nepal. As a Bay Area native, she has witnessed some of the changes taking place, bringing her focus closer to home.

Cite as: Caprio, Emi. 2018. “Affective Landscapes of the Past and Present in Santa Clara.” Anthropology News website, November 9, 2018. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1033