Article begins

Former white and middle-class cocaine and cannabis dealers talk about their often contradictory “careers in dope.”

When anthropologists and sociologists study illegal drug dealing (or anything else), we tend to be wary of such economic orthodoxy as “self-interest.” Our analyses rely, instead, on culture or subcultures or deviance with attention to how social inequalities give rise to patterns of behavior.

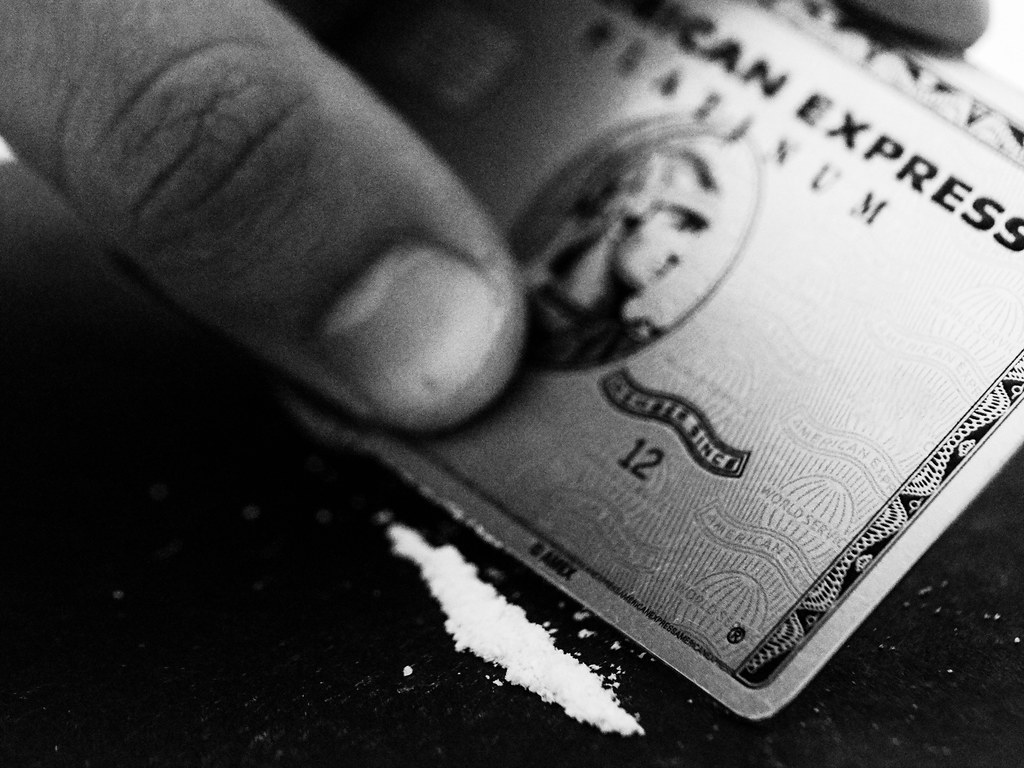

Drawing a line of cocaine. danielfoster437/Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Deeper dynamics of drug dealing

What happens when dealers are not poor, brown, desperate, or suffering any evident structural disadvantage? Are white, middle-class drug deals sensibly understood in terms of social alienation, deviant or subcultures, or rational self-interest? It is worth noting that this privileged sort of illegal business is statistically predominant. White people take drugs at the same rates as others (at least), and they tend to get their drugs from people like themselves. Addressing middle-class dealing is vital to understanding our “drug problem” more generally.

According to Mangai Natarajan, “The vast bulk of research on drug dealing is concerned with retail or ‘street level’ dealing,” a type of business only undertaken by poor people. The focus is rarely on the economics of the dealing, but when it is the assumption is that dealers pursue what economists call “self-interest.” As, Levitt and Dubner write in Freakonomics, “a crack gang works pretty much like a standard capitalist enterprise”. Philippe Bourgois exemplifies this when he claims that “Substance abuse in the inner city [among the crack dealers he is studying] is merely a symptom—and a vivid symbol—of deeper dynamics of social marginalization and alienation.”

Wayne begins by saying drug dealing is just like any other business but shows us how it is not.

This “deeper dynamics” perspective can be compatible with economic orthodoxy. Sudhir Venkatesh, for example, demonstrates that Chicago’s South Side dealers are not the monsters portrayed by the media, but sensible folks making (culturally) reasonable decisions in a tough context. Their evident “reasonability” is enough for Levitt and Dubner to cite Venkatesh in their book. So, while Venkatesh is making a sociological case (reason operates within the social context that shapes it), Levitt and Dubner easily portray this as the “standard capitalist enterprise” argument cited above. Rational actors—meaning everyone—calculate like Roombas set to “self-interest” mode.

The key to this conundrum, I suspected, was the structure of the market: middle-class or “suburban” dealing relies on transactions that occur almost exclusively indoors among friends and acquaintances, and that simple fact transforms the economics. To see what dealers themselves had to say about this hypothesis, I sat down for extended interviews with nine former cocaine and cannabis sellers—mostly white and middle class—and asked them to tell me about their “careers in dope.” As it turns out, their explanations are instructively contradictory.

Suburban drug dealers

Take “Wayne,” for instance. Today he is a businessman in the agricultural sector. He drives a pickup, makes about four times my salary as a professor, and is a devoted Republican. Thirty years ago, however, he was a coke dealer. He did not really want to discuss it, but once I convinced him, he began our interview by asserting that dealing drugs is just like any business, “It’s like the cost of baloney at Brookshire Grocery versus Kroger’s,” and he framed all of his recollections in these terms. He talked of credit, profit, risk, advertising. His product might have been illegal, but business is and always was just business. His logic was straight out of Freakonomics.

However, in the interview I pointed out to Wayne that his own recollections showed drug dealing was not like baloney sales. For one thing, Wayne was selling out of his apartment and he only sold to friends and their acquaintances. Nobody sells baloney that way. Moreover, in Wayne’s sort of drug dealing—as he himself described it—there was lots of “partying” going on. The customers were friends and Wayne shared as much as he sold. (He gave away “tons” of cocaine, as he put it.) The friends / customers also shared with Wayne, gifting back to him the drugs he had just sold them. “That was their prerogative,” he asserted. There were lagniappes, gifting, varying prices depending on context, and complex rituals of consumption. Wayne himself made this clear, and he eventually agreed (when pushed) that “You don’t go fill up your tank at a gas station and then go inside and give the guy a can of gas and hang out with him. But with drugs it’s a camaraderie deal.” So, business among friends is not just business.

Are white, middle-class drug deals sensibly understood in terms of social alienation, deviant or subcultures, or rational self-interest?

“Arthur” provides a different take. He is now a banker, exercise enthusiast, Honda driver, and lifelong Democrat who sold cocaine while he was in college. But, he began our conversation by stating that he was never a drug dealer. His rationale for this was that “it was never about the money,” that in fact he was more of a distributor than a dealer, or really just “helping people out.” But Arthur made lots of money. He described how he and a couple of friends would work collectively, keeping the cocaine in a particular sack, to which they added the money when they sold the drugs. (Arthur was unique in my interviews in that he worked in a kind of three-person collective rather than alone.)

Here, too, I pointed out a contradiction by our third interview. If Arthur was just selling for fun, or altruistically, for what the drugs cost him, how did the sack fill up with money? Surely, he must have been selling for more than he had paid, so I pressed him on how he decided on prices. We went back and forth on this, and eventually it became clear. The members of his collective paid nothing for drugs. Close friends paid slightly more than the wholesale price, generating a small profit. More distant friends paid more. These “more distant” friends were the reason the collective paid nothing for their own drugs and still made money. When this became apparent Arthur called it “totally fucked up.” In essence, I had unkindly made him understand that he had been, in his words, “putting a price on friendship.”

Ambivalent economies of drug dealing

So, Wayne begins by saying drug dealing is just like any other business, but shows us how it is not. Art begins by saying drug dealing was not a business, but shows us how it was. This illustrates the ambivalent economics at the heart this sort of drug dealing. In short, it shows that it is impossible to frame social behavior as purely self-interested (as Wayne tried to do), but equally impossible to call the behavior merely social (as Arthur sought). Durkheim argued long ago that humans have a “double existence that we lead simultaneously: one purely individual, which has its roots in our organism, the other social.” This is as true for dealers as it is for the rest of us, and, as I argue, such ambivalence is better explained by neuroscience, behavioral economics, and classic work by Marcel Mauss than by simple versions of culture, oppression, or economic rationality.

David Crawford is professor of anthropology and director of international studies in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Fairfield University. His early research focused on the Moroccan High Atlas, for which he won the Julian Steward Award. He recently moved to explore themes in economic anthropology in the US suburbs and is the author of Dealing with Privilege: Cannabis, Cocaine, and the Economic Foundations of Suburban Drug Culture.

Walter E. Little ([email protected]) is contributing editor for the Society for Economic Anthropology’s section news column.

Cite as: Crawford, David. 2020. “Ambivalent Economics of Middle-Class Drug Dealers.” Anthropology News website, March 5, 2020. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1369