Article begins

Modern nights are notoriously bright, blending day into night with an overabundance of artificial lighting that makes sky glow visible from outer space. Many of us take the night for granted, and if we think about ancient nights at all, many might assume that people in the past spent half their lives in darkness, slumbering until the sun rose and shone brightly. And surely, there would be no evidence for ancient nights before historical times.

Archaeologists primarily excavate during daylight hours, and most contemporary artistic renderings of sites are shown basking in the sun. As a result, archaeologists have long favored the daytime in our reconstructions of the past, a condition that Hilary Orange refers to as daycentrism.

Perhaps these reasons are among the many why most archaeologists have not typically included the night in our investigations of the past. Yet delving deeper into the hours of darkness reveals ancient activities across the globe and throughout human existence, from the Paleolithic onward. Using the night vision that an archaeology of night provides, explorations into the dark show that nighttime was simultaneously relaxing and taxing. From the cave to the city, ancients conducted their nightly business: hunters, cooks, entertainers, artisans, guards, farmers, servants, attendants, soldiers, scientists, and monarchs performed an amazing array of activities that took place from dusk to dawn.

This re-envisioning of the past through the study of material remains, inscriptions, art, historical records, and observations of living peoples is enlightening in many ways. But no new data are needed to convert to the dark side of archaeology. With intentionality, nocturnal practices emerge and develop into nightways through the paraphernalia of the past, a concept David M. Reed describes as “the cross-disciplinary study of nocturnal customs, behaviors, habits, and items of a group of people to understand the anthropological complexity of nycthemeral practices.” A clay bowl, a raised platform, a grinding stone: archaeologists recover these items throughout the ancient world, yet once we recognize their nightly qualities and how they symbolize the night, they become far more insightful than simple realia.

The night was a potent force in ancient Mesoamerica, the darkness filled with danger, drudgery, sacrifice, royal accession, performance, and more. How do we know about what the Late Classic Mayas (600–900 CE) did at night? A parallax perspective facilitates new interpretations of art, objects, and features that reveal dark doings across the social spectrum. Methods old and new further our pursuit of the night, making Classic Maya nights shine brightly. Advancements in deciphering an ancient script give glimpses of royal pursuits in the dark, as we shall see.

Rulers and common folk alike appreciated the sacredness of the night. At the seventh-century farming community of Joya de Cerén in El Salvador, residents carefully stowed away in their humble homes precious objects used in rituals. We know about this practice because a volcanic eruption covered the entire community and preserved organic materials rarely found under normal circumstances. A sharp obsidian blade wisely placed on a high shelf contained the telltale traces of autosacrifice: human blood. This substance was the ultimate offering to one’s ancestors and nighttime was the ideal time to petition and supplicate them.

Royals did it, too. In the heart of the Maya lowlands, on a propitious October night in 709 CE, Lady K’ab’al Xooc, Queen of Yaxchilan, engaged in bloodletting, lifting a thorn-lined rope to her tongue (figure 1). Her dripping blood soaked the bark paper below, an offering she would burn in remembrance of noble ancestors. Her husband, King Itzamnaaj B’ahlam II, supported a heavy fiery torch to illuminate the darkness, the fire itself a symbol of life.

Later in the 700s, in another Maya city, now known to us as Piedras Negras, a scribe skillfully recorded details of royal feasting and celebrating, etching them in stone for posterity to commemorate midnight festivities of drinking fermented cacao and dancing among allies and former enemies on this auspicious date. Feasts and festivals on all scales, as well as once-in-a-lifetime coronations, would take place at favorable times, lasting several days and nights, requiring torch-lit causeways, plazas, and buildings throughout the gathering period. Such an event occurred at Joya de Cerén on a hot August night; farmers were preparing for a celebration with copious amounts of manioc beer, and then the volcano erupted, ending it all.

During the Classic period, the peaceful transition of power was often presided over by Maya kings who knew how to exploit the moon to enhance their lunar power: numerous accessions to the throne were arranged when the moon shone brightest, or not at all. In the southeasternmost realm of the Classic Maya in the city of Copan, Honduras, its ninth king, Sak Lu, was enthroned on a date when the moon was shining at full capacity. Details of such remarkable events were worthy of being inscribed for future generations.

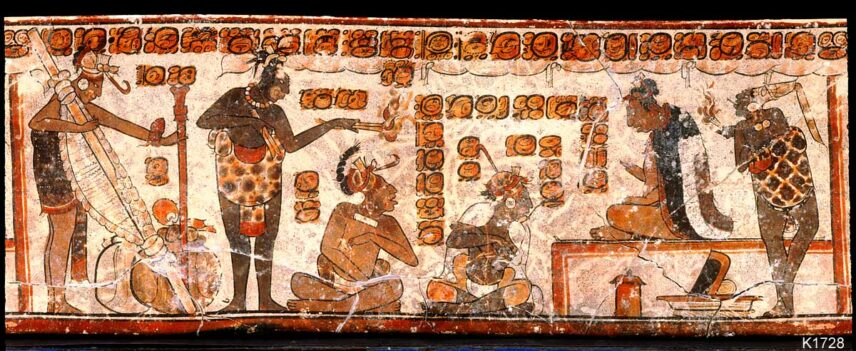

Yet not all was peaceful in these nights. Causeways that cross-cut cities and less formal paths in the country facilitated movement for friend and foe alike, night and day. A story in image and text painted on the walls of a limestone structure at Bonampak, Mexico illustrates a bloody nighttime skirmish of chaos and spears, successfully led by King Yasaw Chan Muwaan and his sons in the late 780s (figure 2). These murals, three rooms in all, reveal incredible details about the dedication of an heir to the throne (room 1), a nocturnal battle (room 2), and a dance to celebrate victory (room 3). They reveal facets of Maya life during the last decades of the Classic period, night and day. Raids after dark employed many: soldiers, leaders, healers, astronomers, standard bearers, torch bearers, scouts, guards, and others needed to successfully surprise the enemy.

Extraordinary events shine through historical documentation from accomplished scribes and artists, while, like other practices of the everyday people of history, the ordinary dark doings of the past require a beacon to see them. Archaeologists count on the routine and mundane to reveal daily practices, but how do such objects reveal nightly practices? It happens through a parallax perspective that takes in numerous angles, it happens through an archaeology of the night. Sometimes this beacon is an archaeologist’s keen observation of a pottery vessel that was repeatedly scorched from holding fire to provide comfort in the dark and chase away the bugs. The use of advanced geochemical methods helps us to detect patterns of habitual use, while the detailed readings of living cultures and historical records lend humanistic insights and provide clues about how objects were integrated into nightlife.

In Late Classic Copan, for example, urban artisans were burning the midnight fuel to make a deadline, manufacturing fine shell jewelry commissioned by a noble. As the craftspeople labored late into the night, they had to refill a vessel with charcoal, a substance that gave them just enough light for working and added a bit of warmth to the damp tropical night. In the regal palace of La Corona, Guatemala, skilled workers were treating mercury-laden cinnabar with special care, keeping their braziers illuminated during their long work hours to produce the rich vermillion paint for decorating architecture and objects. The night shift at La Corona also included cooks and servers who provided refreshments for the palace people and kept the hearth fires burning. Such nocturnal activities became visible through careful excavations, soil analysis, and advanced geochemical methods.

Painted pottery viewed with night vision conveys nocturnal habits. Throughout the Maya realm, politicians and their attendants worked overtime into the wee hours of the night, one of them enjoying a smoke of godly tobacco, a symbol of the night for the Classic Mayas (figure 3).

Just as some kings planned their coronations in sync with the moon’s orbit, other Mayas prudently scheduled particular household activities around the lunar cycle to ensure favorable conditions were optimized. And with most people spending most nights at home, the footprint left behind from such activities should be just as visible as those from diurnal ones through the lens of nighttime household archaeology. Houses after dark were busy locales; contrary to popular belief, not all were snug in their beds! Cooks carefully placed corn kernels in pots with lime to facilitate their processing on manos and metates during the early hours of the morning. Such grinding stones were put to good use in producing ground maize for the next day’s meals or making manioc beer for pending celebrations. Women typically rose before dawn to re-energize the hearth before taking on the task of making breakfast to nourish their family throughout the day.

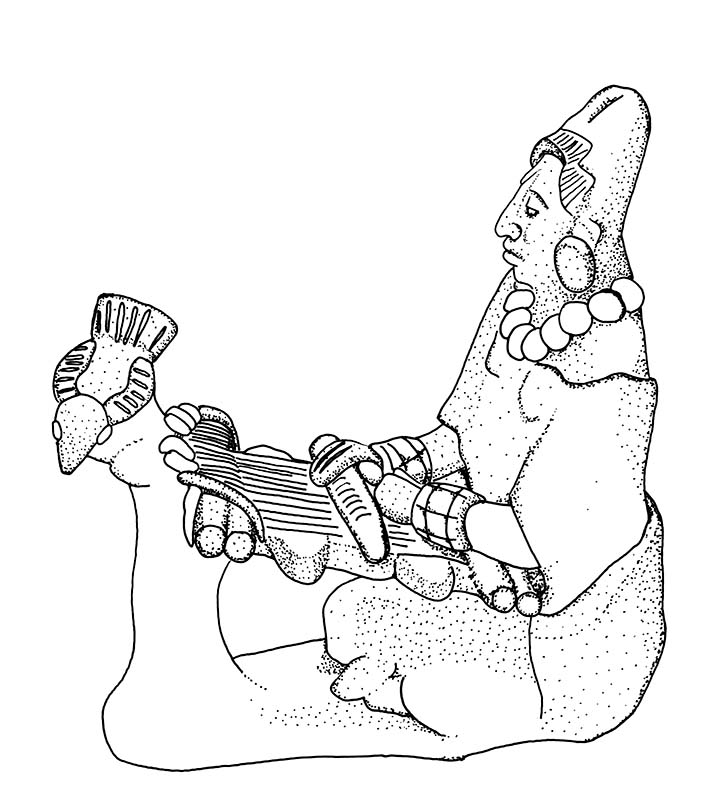

Spinning and weaving, critical contributions to the household economy, could be undertaken by women during the quieter and cooler hours with minimal light, and especially after children had been settled in for the evening. The Moon Goddess, patroness of weaving, guided the artisans’ repetitive motions. Keen observations from night ethnographers provide glimpses into nocturnal activities, the materiality of which can be tied to remains of Classic Maya houses of varying statuses. Ethnographically observed crafts, such as spinning and weaving, are materialized in the archaeological record where spindle whorls for spinning yarn have been recovered from household excavations (figure 4a), and ancient figurines depicting women weaving come from various locales across Mesoamerica (figure 4b).

When it did come time to rest, there were choices for getting a good night’s sleep. Social status and inequalities were expressed through a plurality of adaptations―a stone roof over the queen’s head, while the commoner slept on a mat under a thatched roof or under the stars of the hot tropical night. At Joya de Cerén, an inhabitant had stashed a sleeping mat in the rafters of an adobe house, and incredibly, excavators recovered it several centuries later. Residents creatively used the loop handles broken off from pots and embedded them into clay walls to hold curtains that were pulled together as they bedded down for the night. Elite Maya benefitted from built-in durable cord holders, fine cotton cloth, and fires safely contained within pottery vessels (figure 5) to ward off the dark, damp interiors of stone palaces. Nightworkers took care of the higher classes, and only after noble needs were satisfied could they retire and regain their own strength for the coming day. Such occupations are often invisible and taxing, as Julius-Cezar MacQuarie shows in his contemporary night ethnography with market loaders and other workers who labor through the dark.

Nightly activity outside the house ensued with great fervor as well, taking people out of the safety and security of their abodes. Farmers utilized the dark to great effect to feed their own families and burgeoning urban populations. The moon enhanced crop growth, and during harvest times, many hands were required to collect and protect the bounty. Household members kept vigilance in the fields to guard precious ripe corn from deer and other animals; a quickly built field hut could offer protection from both the elements and unseen hazards.

For hunters and fishers, moonlight also played a role in the household economy. A full moon illuminated nocturnal beasts during the hunt, while torchlight and moonlight attracted fish in glimmering rivers and lakes, making them easier to catch.

Maya houses after dark could be dangerous places, where snakes, scorpions, and spiders lurked in shadowy corners, whether of humble houses or grandiose palaces. Care in the night was essential, especially for the inhabitants of flammable domiciles, where fire could spread easily from burning hearth to roof and wall.

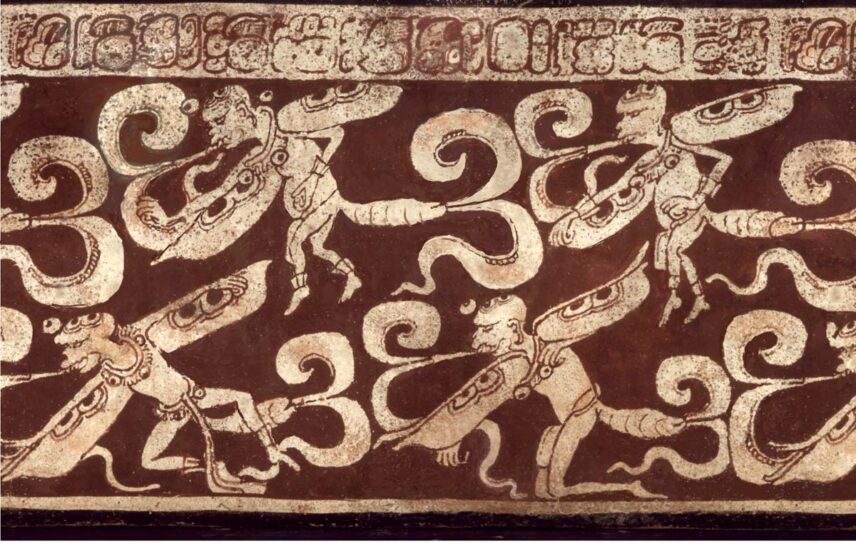

Furthermore, danger was found in the dark corners of the Maya universe. Evil powers in the form of some crepuscular and nocturnal creatures carried disease, destruction, and death, such as the unsavory wahy beings that haunted those who ventured out into the night. It was folly enough to be walking alone in the dark with a torch to guide one home, but woe to the individual who chanced the night without any light at all. Sinister forces waited to pounce on the unaware, with sorcerers and ghosts waiting hungrily in anticipation. All had to be wary of the dangerous supra-human beings that wandered about at night, whether one was farming, fishing, politicking, or up to no good.

The night had its own aroma particular to time, place, season, and culture. From botanical and faunal remains at archaeological sites, it is possible to reconstruct the ancient landscape and connect those species to the dark, creating a nightscape. Using knowledge of plant species associated in Maya ethnographic contexts with the night, paleoethnobotanist Venicia Slotten tied those same species to ancient practices where they have been recovered from archaeological sites in the region. Sensory experiences abounded in the neotropical lowlands of the Classic Mayas and their nights would have been perfumed by sweet-smelling lunar-flowering plants, such as a species of clematis (Clematis dioica L.), while botanists of the past knew to avoid those flowers whose aroma gave one a headache (such as Cestrum nocturnum). Moths and bats fluttered about their blooms, the crackle of fragrant pine wood burned in the hearth at home, and the pungent offering of copal incense from the temple scented the air for ancestors and earthly people alike. Woody taxa were diverse, but the Maya preferred to use aromatic pine (Pinus sp.) and the slow-burning oak (Quercus sp.) for fuel.

The medicinal applications of native plants are well known, some of which relate to various nighttime conditions such as insomnia and night sweats. Have a child who can’t sleep? Apply a mixture of potent leaves (Mimosa pudica, Erythrina standleyana Krukoff, and Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp.) in a bath to induce slumber. And to ensure safety from evil forces, Zanthoxylum wood should be placed around one’s sleeping area.

The medicinal applications of native plants are well known, some of which relate to various nighttime conditions such as insomnia and night sweats. Have a child who can’t sleep? Apply a mixture of potent leaves (Mimosa pudica, Erythrina standleyana Krukoff, and Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp.) in a bath to induce slumber. And to ensure safety from evil forces, Zanthoxylum wood should be placed around one’s sleeping area.

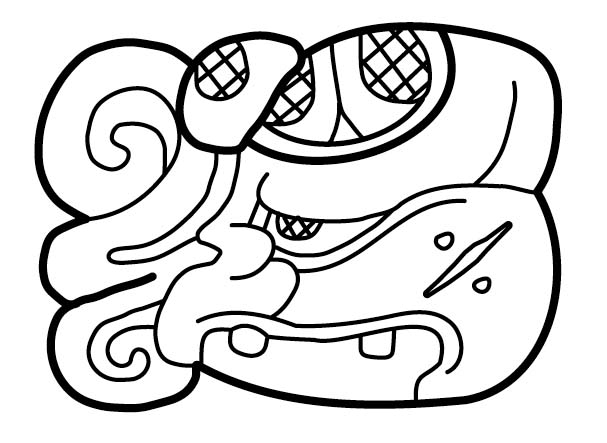

A cacophony of sounds from nocturnal fauna that roamed the landscape added to the ambiance: hooting owls, croaking frogs, grazing deer rustling in the cornfields, screaming foxes defending their territories, and, most intrusive of all, the noisome chirr of insects buzzing about in the dark. Such creatures’ characteristics were familiar to ancients, some of whom drew or created symbols to capture their nocturnal essence; scribes marked depictions of them with the AK’AB glyph denoting night or darkness, such as the firefly (figures 6a and 6b), a beetle intimately associated with the night.

I would be remiss to leave out the allegory of the night and mythological beginnings for the Classic Mayas, ancestral Mesoamericans in general, and an infinite number of peoples whose beginnings hark back to darkness. A dark sky served as the canvas on which bright stars, the Milky Way, and a glowing moon painted the skyscape for astronomers and farmers alike to consult the deities and plan their destinies. The ancestral Mayas were well known for tracking the sun, the moon, and Venus, the three most visible orbs in the celestial vault. Why track these bodies so closely if it were not necessary to do so? Skilled astronomers inserted their knowledge into architectural plans that reflected cosmology, and observatories in ancient cities demonstrate the significance of tracking the night sky.

The night played an essential role in all aspects of culture. It permeated mythology, ritual, warfare, politics, entertainment, craft production, subsistence, and the household economy regardless of one’s position in Classic Maya society. From an anthropological perspective, peoples of the past integrated darkness and the night into their lives, making the incorporation of the night fundamental for modern understanding of ancient lifeways. The nightscape is as much a part of our cultural heritage that deserves recognition and preservation. Whether remarkable or routine, nightways constituted a critical component of life in the past, just as they do today.

Author’s note: Sincere thanks for the expert advice from K. Viswanathan, Christine Dixon-Hundredmark, Steve Houston, Scott Hutson, Katharine Hunt, David M. Reed, Meghan E. Strong, and AN Editor Natalie Konopinski. Gratitude is due to Christina Halperin, Justin Kerr, Mary Miller, David M. Reed, and David Webster for generously sharing their images, and to the British Museum.