Article begins

The pandemic has made working from home the new normal for many people. University academics are no exception. Scenes of work amid everyday life have become a familiar sight. In 2020, a tweet sent by environmental engineer Gretchen Goldman revealing the chaotic realities of juggling parenting and work, sparked much discussion.

The tweet was about her interview with CNN on September 15, 2020, which was conducted remotely from her home. Dressed in a suit jacket, Goldman, as she appeared on CNN, was the picture of professionalism. But outside the screen’s frame, the room was cluttered with the toys of her two children, aged two and four. From the picture, we can well imagine Goldman playing with her children right up until the interview and scrambling to throw on a jacket at the last moment.

Goldman’s tweet, titled “Just so I’m being honest,” quickly went viral, receiving more than 300,000 retweets and 2.8 million “likes” in a single day from readers for whom the scene was all too familiar.

As is evident from the term “work-life balance,” we have often treated work and life as separate and have sought a better balance between the two. The coronavirus pandemic, in an instant, tossed the two together into a blender. Feminist anthropologists may say, however, that the two have always been intermixed, challenging the dichotomy between private and public by moving beyond the formal spaces of waged work to recognize other more intimate sites, such as the household and the family, as spaces where work also takes place and hence as constitutive of global capitalism.

A Japanese Marxist feminist, Ueno Chizuko, in dialogue with a feminist comic writer Tabusa Eiko, has also discussed the gendered boundaries between public and private domains in the Japanese context. They use the word “A-side” and “B-side” to express the dichotomy between masculine and feminine domains:

I believe that society has an A-side and a B-side. Things like politics, the economy, time, and employment are part of society’s A-side. The B-side includes things like reproduction, care for the aged and children, illness, disability…. Men live on the A-side. Women also start out living on the A-side but are forced to go to the B-side when they have children. Men can also be forced to switch sides by illness or injury; but, as a general rule, they are able to stay on the A-side. Women have to move back and forth between the A-side and the B-side. For example, they may be told by a hospital on the B-side that they are “at risk of having a miscarriage and need to have a break from work,” setting up a struggle to make arrangements with their employer on the A-side. (Author’s translation of the original text in Japanese)

As can be seen from their apt descriptions, work on the A-side is generally signified as something that requires perfection, no ambiguity or vulnerability. From such a standpoint, life on the B-side might appear to be more fluid, where messiness, unpredictability, vulnerability, and, at times, contradiction, are par for the course. As Ueno and Tabusa and other feminists have observed, men hold privileges to keep the two domains relatively separate.

Goldman’s post brought into full view the reality of women juggling work and life, or A-side and B-side. That said, the pandemic has forced many people, not just women, to confront the blurred boundaries between these apparently distinct domains. It has shown that our lives—which include our homes, relationships, and emotions—exist at the same time and space as work. In this post-pandemic age, it is meaningful to rethink the separation between work and life that underlines the concept of work-life balance, and to imagine a new relationship between them.

Exploring this topic as an anthropologist in 2020 proved challenging as long-term, immersive investigations—traditional fieldwork—were difficult. I once again turned to feminist anthropology which at historical junctures has opened up hegemonic categories to “advocate for rebellious and liberatory alternatives.” The separation of work and life is a hegemonic categorization that needs to be questioned in a post-pandemic society. But it is not just conceptual categories that feminist anthropologists have addressed. They have also interrogated racial and gender biases in the methods of research and disseminations themselves. For instance, an inspiring body of work within “A Manifesto for Patchwork Ethnography” has called for an examination of the impacts of personal lives in shaping anthropological fieldwork and the type of knowledge produced. Feminist anthropologists have also advocated for more collaborative and accessible ways to conduct research and disseminate findings by going beyond the use of texts to use other sensory modes, such as needlework, images, dance, and art.

Taking inspiration from this feminist anthropology, I designed an ethnographic experiment to understand life and work as intertwined processes in time and space. I focused on a segment of society that was familiar to me—researchers—to explore how their work was intermingled with the rest of their lives. Researchers included nonanthropologists, from sustainability scientists to engineers to economists. This reflected my own positionality in 2020 as an anthropologist working at an interdisciplinary institute. The experiment was also designed at a time when face-to-face long-term fieldwork was not possible. I was also on a short-term contract, which guaranteed no long-term relationships with the participants even if I desired one. Just as feminist anthropologists have theorized the intertwining of the personal and the professional, the need to generate an innovative methodology came out of the very domains of life characterized by health concerns, care for research participants and family members, and the temporality of contract insecurity.

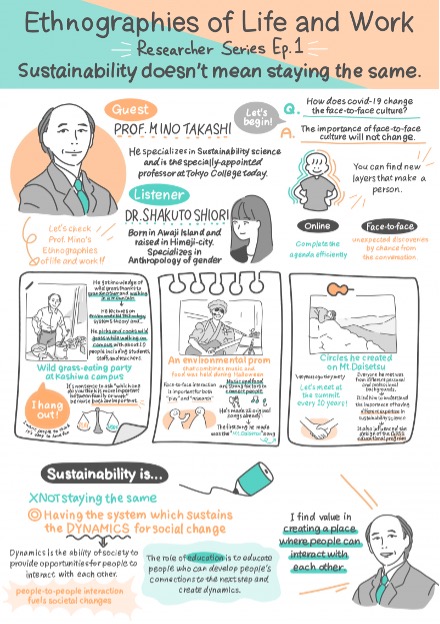

In such a “life” context, collaborative Zoom dialogue became my field method. I asked researchers from the University of Tokyo, where I was based, to select three photographs that represented life for them. I invited them to share stories over these photographs, including those that were not explicitly shown in the images. In this experimental ethnography, instead of long-term participant observation in a community in which I supposedly immerse myself with an emic perspective, I invited interlocutors to reflect on their practices through a series of photographs they had chosen. My role as an anthropologist was to facilitate the dialogue; in many instances, my interlocutors led the discussion—the dialogue led to interpretation, which was shared with the interlocutors. This, in turn, led to another dialogue. I also invited a graphic recorder to record our dialogues in the form of graphic ethnography, a form that has gained increasing traction among public-facing anthropologists as it combines “the best of text (linear narrative) with the strength of images (quick, affective, and holistic interpretation)” to speak to diverse audiences in engaging and accessible ways. Many times, what graphic recorders decided to highlight in their visual work differed from what I highlighted in my writing. Such differences themselves provided new insights and allowed for more dialogue between the interlocutors, the graphic recorder, and the anthropologist. The written ethnographies and graphic recordings were published as open-access blog posts on the University of Tokyo’s website to encourage further dialogue with a public audience.

The ethnographic experiment brought to light unexpected, and even more so, unexpectedly productive, connections between work and life in the academic ecosystem.

For example, for Mino Takashi, an engineer who was a coordinator of an interdisciplinary program in Sustainability Science, it was decades-long relationships with people he met at Mt Taisetsuzan in Hokkaido that shaped his approach to researching and teaching. For the past 40 years, he climbed Mt Taisetsuzan every 10 years to reunite with fellow climbers. They came from various work backgrounds, from salaried men to CEOs to primary school teachers to timber workers to fish ball sellers. Through conversations with them, Mino learned that the dynamics of interactions between differently situated people and nature can generate a force for social change. “Sustainability does not mean continuing the same thing,” he said, “sustainability means maintaining the dynamism that is needed to sustain change.” He highlighted the importance of applying diverse value systems to understand a given issue. Diverse viewpoints can give rise to uncertainty in the first instance, yet uncertainty is part and parcel of the dynamics. Mino became convinced that the role of education was to nurture people who can develop these dynamic connections to create positive social change. He designed a Sustainability Science curriculum in which students were expected to work with different experts, including nonacademics. “Once, I happened to sit next to a Buddhist monk in a restaurant. We hit it off, and I ended up inviting him to participate in a workshop on the theme of religion and sustainability.” He grinned.

The dialogue with Mino Takashi served as an opportunity to take a fresh look at connections, rather than balance, between life and work. Diverse groups of people he met over 40 years of visits to Mt Taisetsuzan have since become his research collaborators. Despite the prevalence of the concept of work-life balance and the underlying idea that work and life are separate things, researchers regularly and strategically allow them to merge and influence each other. Not only are they intertwined, but the connection is also often productive, positively influencing the entangled domains of work and life.

Life, or intimate personal domains, should not necessarily be conceived of as something that can interrupt or constrain how we work, but rather as something that can enhance and positively change how we work, and the knowledge that we produce. We can highlight these beneficial aspects of the blurring while also continuing to acknowledge the limits that are experienced by differently positioned peoples.

As we expand anthropological methods and the ways in which we work and live, feminist anthropology has many contributions to make. This ethnographic experiment shone a new light on the value system represented by “work-life balance,” challenging the dichotomy of work and life as separate things, which lies at the root of patriarchal knowledge production processes. I hope this ethnographic experiment can contribute to a wider dialogue with feminist anthropologists who have always, and continue to, advocate for a kinder anthropology.

Author note: This research was supported by JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists 2021–2023, “Beyond Work-life Balance: A Feminist Anthropological Approach to Gender Equality.” For more information about the project read an introduction and English translations of other interviews and recordings with Mino Takashi, Fukunaga Mayumi, and Hoshi Takeo.

María Lis Baiocchi and Leyla Savloff are contributing editors for the Association for Feminist Anthropology’s section column.