Article begins

As a black woman, I have found it difficult to position myself as a scholar within the field of anthropology while grappling with the complicated history of the discipline.

Throughout my career, I have rarely seen myself accurately represented, and instead, I see black people as objects of study to be curated and defined by those who hold academic authority. This year, Adam Netzer Zimmer and I co-organized a roundtable titled “Black Feminist Science” in order to facilitate a discussion of how black feminist theory might aid anthropologists in better understanding the various forms oppression takes, while reconsidering what makes us scientists. The knowledge and experiences of black women have been undervalued in the United States, primarily in the production of scholarly work. bell hooks argues that black women have been systematically ignored, objectified, othered, and “socialized out of existence.” As a result of this systematic exclusion from the academy for hundreds of years, the intellectual works of black women do not always fit the mold of what white, Eurocentric, and male intellectuals have considered “scholarly.” Many black women scholars, activists, and artists draw on their lived experiences to analyze various systems and structures of oppression through media, including poetry and fiction. We must recognize that what is considered scientific and/or scholarly has historically been socially constructed, and remains subject to the researcher’s political and intellectual context. Suppressing the intellectual traditions of an oppressed group enables dominant groups to maintain control: the invisibility of the oppressed being equated with a lack of dissent to the dominant narrative. Therefore, the intellectual endeavors of marginalized black women have historically represented radical challenges to structures of knowledge and systems of oppression.

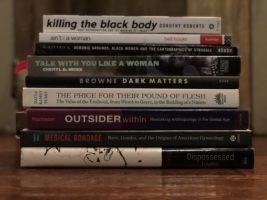

Stack of books showing the enriching intellectual works of black women. Aja Marie Lans

Kimberle Crenshaw (1989) is credited with coining the term “intersectionality” to provide a framework for understanding the interconnectedness of oppressive institutions and ideologies. To Crenshaw, the various forms of oppression faced by black women based on their race, gender, and sexual identities, could not be examined, understood, or dismantled in isolation. While she may have been the first to give this analysis a name, the method she advocated for had been in use by many black women scholars prior to her work. Crenshaw centers black women’s experiences to overcome our historical erasure and to illuminate how discrimination occurs along multiple axes, making black women multiply-burdened. Black women might sometimes experience discrimination similar to how white women do, and other times more similarly to black men, but often experience double-discrimination. The use of the word “woman” often implies white woman, while the use of “black” often refers only to black men. These systems of oppression cannot be remedied simply by including black women in already established structures, but instead by using a new analytical framework that addresses the experiences and concerns of black women.

As a bioarchaeologist, I grapple with the ethics of studying human remains, but also see the opportunity to (re)insert corporeal beings into wider discussions of history.

There have been calls to apply black feminist and intersectional frameworks to historical archaeology by scholars such as Maria Franklin and Whitney Battle-Baptiste. Using a black feminist framework reinforces the notion that black women are worthy of study and allows us to define ourselves rather than recreating society’s stereotypes of black women. Archaeology plays a critical role in deconstructing stereotypes of black women and shedding light on the lives of everyday women who did not leave much behind. Archaeologists have the potential to contribute to collective black history and memory, and to help black folks reconstruct their histories from a more politically aware viewpoint.

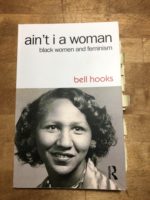

In ain’t I a woman, bell hooks examines through her personal accounts how black women, from the seventeenth century to the present day, have continued to be oppressed by both white and black men, even by white women. Aja Marie Lans

This is not to say that the experiences of all black women are universal. Rather, it is recognizing that in order to practice a more accurate form of archaeological inquiry, the lived experiences of black women must be centered in any study. However, it can be argued that our shared location in American society means we have a collective group history across time and often face injustice in the same social settings. We are oppressed, or systematically denied access to resources of society, through the economy, polity, and ideology of our nation, which function as a system of social control to keep us subordinate.

Archaeologists have the potential to contribute to collective black history and memory, and to help black folks reconstruct their histories from a more politically aware viewpoint. Drawing on the work of Patricia Hill Collins, I have come to position myself as a black woman with the view of an outsider within. I am a member of a historically disempowered and marginalized group with access to forms of elite knowledge, utilizing social theory and producing knowledge within a field that has traditionally been dominated by white men. From my position, I am able to rearticulate the stories of the black women in this collection and lend my own critical insights into the history of oppression, and therefore, to challenge the doctrines of a discipline long defined by an exclusive group. We must define ourselves so that others do not define us, and my goal is to restore humanity to the long objectified remains of these women.

Aja Marie Lans is a doctoral student at Syracuse University and a 2018 Diversity Travel Award winner for the Archaeology Division.

Sandra L. López Varela is contributing editor for the Archaeology Division.

Cite as: Lans, Aja Marie. 2019. “Black Feminist Science.” Anthropology News website, March 18, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1118